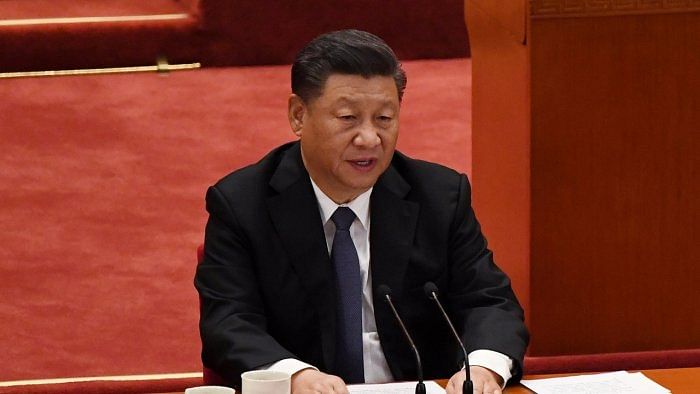

Chinese Communist Party supremo and President Xi Jinping is up against a number of challenges at the same time. On the economic front, a housing market collapse is brewing in China. It is manifested in the form of Evergrande, the second-largest real estate company in China (which has also expanded into several unrelated lines like owning a soccer team and electric vehicles manufacturing with massive borrowing using government and party connections) being unable to service a huge debt burden in excess of $300 billion.

This is hurting ordinary Chinese people who have gone for houses as investment options rather than for residential purposes for decades, taking loans from financial institutions using houses as collateral. Now they are either unable to get the promised houses delivered (as the debt-laden builders fail to finish the projects) or find the value of their investments and wealth plummeting with the falling prices of houses. As prices drop, the fire sell by builders and ordinary investors is creating a downward spiral in real estate and property prices. The negative wealth effect would lead to less spending on other goods and services and the contagion impact on financial institutions as a result of debt default would affect the health and the ability of the financial system to extend loans to other prospective consumers and investors.

Further, Evergrande is not a stand-alone episode. It is a symbol of credit-fuelled overexpansion of many Chinese businesses (encouraged by the Chinese governments at Central, regional and local levels for growth of jobs, incomes and tax revenues) for decades which is simply not sustainable indefinitely. The debt to GDP ratio of China has risen rapidly from 144% in 2006 to reach an all-time high of 280% in 2020 (BIS data).

In a sense, President Xi is bringing these latent problems to the surface by asking the financial institutions not to extend further loans to troubled real estate companies and put a halt to this credit-fuelled overexpansion. Xi is using Evergrande as a kind of warning to many such business magnates building their industrial empires using their exalted connections, starting with cutting down to size Jack Ma, the best-known international symbol of the Chinese ‘new rich’.

But Xi is facing a dilemma here. The crusade against big business is a move intended to increase his popularity with the masses and strengthen his grip over the party. However, to the extent it is hurting ordinary people and smaller businesses by cutting down the flow of funds and reducing employment income and wealth, it may backfire for Xi. So, he is most likely to soft-pedal his economic rebalancing initiative in the interest of social stability and his own political future.

The second economic challenge before China is the growing power crisis. In part, this again is the result of Xi’s recent economic and political moves. Xi wants to project himself as a responsible rising power on the global stage by agreeing to cut CO2 emission per head and setting immediate targets for reduced pollution. To this end, he wants to switch the source of power generation from coal to renewable energy, if necessary, by rationing conventional power among competing ends. The problem has been accentuated by the political decision of Chinese government to cut imports of cheap coal from Australia (a member of the anti-China alliance of QUAD nations) whom Xi considers a major political adversary in the Asia-Pacific region. This has led to the sharply rising cost of coal. But the power generating companies are not allowed to commensurately raise the price of power which has reduced the incentive to generate coal-fired power.

Housing market crash

The economic fallouts of the looming housing market crash and power crisis would most likely reduce the growth prospects of China in the immediate future. The intended diversion of resources from overbuilt housing and infrastructure sectors to high-tech manufacturing and green industries would take time to offset the decline in the old industries. The resulting growth slowdown would further boost the ongoing trend of both Chinese and foreign investors to move industrial plants from China to lower-cost (especially labour cost) locations like Vietnam and Cambodia and Chinese savers to export capital abroad instead of investing within China.

The economic forces described above have been further accentuated by the growing animosity and distrust between China and the Western powers. The formation of the anti-China bloc called QUAD involving the USA, Japan, India and Australia and the tendency of many countries to reduce their over-dependence on Chinese materials and components in the post-Covid world are working against imports from and investing in production facilities in China. As a result, Chinese savings and investment would seek further outlets in other countries (in Asia, Africa and Latin America) along the lines of the so-called Belt and Road initiative of President Xi.

Though this would benefit the Chinese economy by creating demand for materials and components from Chinese industries and Chinese engineers and high skilled workers (often built into the terms of contracts in the infrastructure projects financed by Chinese loans), it would also fuel the already existing anti-Chinese sentiments in these countries as the political leaders would like to shift the blame for their economic woes and debt-servicing problems on the new ‘Chinese colonists’ replacing the Western colonial masters.

How is the rest of the world going to be affected? Unlike the housing market crash in USA which triggered the Great Recession of 2008-09 in many countries of the world (as the risk of housing loan default in USA was spread globally by selling risky mortgage-backed securities to the financial institutions of such countries), the rest of the world’s financial system is mostly insulated from the debt-financed expansion in Chinese real estate business. By the same token, China will not be able to export some its problems to the rest of the world the way USA was able to do. However, any disruption of supplies of raw materials, components and finished products from China would surely affect the economies linked to Chinese supply chains by creating cost-push inflationary pressures.

(The writer is a former professor of economics at IIM Calcutta, India and Cornell University, USA)