The Bahugunas’ involvement with the Chipko movement and opposition to monocultures instead of the original mixed forests of the Himalayas is better known than their intervention against the Tehri Dam Project.

DH ILLUSTRATION: Deepak Harichandan

Papri Sri Raman

As we bid farewell to 2023, we chose one of India’s greenest states, Meghalaya, to visit. It boasts rivers and waterfalls, the cleanest village, and the rainiest small town in India, Cherrapunji.

Yes, the view from the Shillong guesthouse was exotic; the sky was clear and blue; Cherrapunji, however, wasn’t the wettest place on planet earth; Maysinram nearby was, and in August 2023, Rishikesh had the most rains. However, what strikes visitors to Meghalaya most is the long line of trucks facing south towards the Bangladesh border, all carrying stones.

They are natural stone blocks from the Jayantia hills, as old as the Malwa plateau that peters out at the Rajmahal end of the Deccan. After a narrow gap, the Shillong plateau starts at the foothills of the Garo-Khasi-Jayantia ranges, technically also peninsular India’s extensions. The gap between the two plateaus is bridged by silt and seeds from the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers. So these lower hills are also part of the Greater Himalayan Ecosystem, the lush forests, which are very similar to those in the Himalayan ranges.

“For most people, the Himalaya is a storehouse of enchanting scenic beauty. Its snowy peaks, densely forested hill slopes, rivers and lakes, and green villages have been attracting nature lovers, spiritual seekers, pilgrims, poets, and artists for centuries. But the glory of this magnificent mountain is fast receding. We could see the receding glaciers, barren hill slopes, muddy rivers, lakes, and valleys fast changing into deserts,” wrote Sunderlal Bahuguna in the 1980s, following a Kashmir to Kohima padayatra (a foot march) he and fellow social activists undertook to assess the impact of human interference in the Himalayas.

The states they covered were Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, and Nagaland—the entire west-to-east swathe of the mighty Himalayas—that have not only served as this subcontinent’s toughest sentinel against marauding invaders but also provided us with life-sustaining waters for drinking and agriculture and our cultural bastions, the holy rivers.

Sunderlal Bahuguna (January 9, 1927–May 21, 2021) and his wife Vimla were far ahead of their times. Many decades before the UN Framework Conventions were charted to save the earth’s environment, before climate change became the world’s most important issue and green projects became fashionable, Vimla and Sunderlal Bahuguna attempted to make environment protection a catchword for human survival. For his efforts, Sunderlal was awarded the alternative Noble Prize, the Right Livelihood Award in 1987, and Padma Vibhushan in 2009. Fifty years ago, they saw the ecological harakiri in the Himalayan hills that spelled catastrophe for the people of the countries living in its lower reaches.

Bahuguna’s team provided a detailed report (called the KKM Report) on the forests of each and every Himalayan state they visited. On Nepal, the KKM Report said, “The disastrous effects of deforestation are evident in Nepal. The hills have already become barren. The precious topsoil has eroded. It is estimated that 240 million metric tonnes of precious top soil are exported from Nepal. It has raised the river beds, and floods in the foothills have become a regular phenomenon”. This is equally true of all the Indian states in the Himalayas. Today, these exhaustive reports cannot be found even in the dungeons of government vaults.

The Bahugunas’ involvement with the Chipko movement and opposition to monocultures instead of the original mixed forests of the Himalayas is better known than their intervention against the Tehri Dam Project (TDP). ‘In 1980, Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India, wrote to the Department of Science and Technology about the need for a reconsideration of TDP. Subsequently, the department set up a committee of experts to assess the project. In 1986, the panel recommended halting the project, and the then Ministry of Environment and Forests agreed. Despite all these official opinions, the government went ahead and sought the financial and technical help of the USSR to speed up the project’, writes journalist Bharat Dogra in his biography of the Bahugunas, Guardians of the Himalayas.

On August 28, 1986, the Chairman of the Working Group on TDP set up by the DST made a written statement that the work on Tehri Dam should be halted. In 1990, the Environment Appraisal Committee (EAC), River Valley Projects of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, came to the unanimous conclusion that the Tehri Dam Project should not be taken up.

The EAC report used the word ‘‘unacceptable’’ while discussing the level of risk.

The biography notes: According to the Report, Vol I on TDP, December 1969 (reprint June 1974), the Tehri dam site is characterised by rather difficult engineering and geological as well as seismological conditions... The dam site is 20–25 km to the north-east direction from the main tectonic fracture of the Himalayan region, known under the names of Krol Thrust and Nahan Thrust Zones. Crossing the dam site (fault zone in the bed of the river) perhaps are branches of the main zone of the fracture (Krol Thrust). This report and several more have been buried under the Himalayan bureaucracy.

The recent rescue of 41 men trapped in a collapsed tunnel in Silkyara, a few kilometres north of Dharasu, is much touted, yet there are no words on TV reality shows about the fact that such tunnels should NOT be built in the fragile Himalayas. Following the rescue, Science.org said:

‘For many Indian researchers, the near-disaster was the predictable outcome of officials ignoring repeated warnings from scientists about the dangers of trying to carve a major new transportation system known as the Char Dham National Highway through the highly unstable geology of the Himalayas.

The $1.9 billion Char Dham Roads Plan called for widening roads, boring tunnels, and constructing more than 100 bridges and 3,500 culverts… that ‘would require extensive blasting, clearing large swathes of forest, dumping tonnes of waste, and slicing massive roadcuts into steep hillsides—all activities that could trigger rockfalls, landslides, and floods.’

‘But legal analysts say the government sidestepped requirements for a thorough environmental assessment by chopping the project into segments less than 100 kilometres long, below the legal threshold for review.’ In 2019, the Supreme Court appointed a 25-member High Powered Committee, led by Ravi Chopra, a prominent environmental scientist, to review the environmental impacts of the project. In 2020, the panel said that engineers had failed to analyse the local geology and hydrology at numerous Char Dham construction sites, leading to landslides and environmental damage. India’s military argued it needed the broader roads…’ and in 2021, the Supreme Court okayed the road building.

In early 2022, Chopra resigned from the panel, writing that the experience had ‘shattered’ his belief that the panel ‘could protect this fragile ecology.’ In the apex court, the military always wins.

Today, the Indian Himalayas are a honeycomb of tuiles, and Uttarakhand is a never-ending tragedy. The NDMA has a detailed report on the glacier melt and rock slide that caused the flash flood of February 2021, killing 83 and leaving at least 146 people missing.

Another casualty in January 2023 was the sinking of the pilgrim town of Joshimath, yet the government plans to set up more than 450 hydropower projects in its seismic zone V territories. Himachal Pradesh has planned 27 hydroelectric projects and has signed for a $200 million World Bank renewable energy project.

India’s northeastern region, comprising Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura, is a unique biodiversity hotspot. Successive Indian forest surveys say 75% of the total tree cover loss outside the recorded forest area in India occurred in this region, prone to multiple cycles of heavy floods, grade-V earthquakes, and landslides.

Arunachal has plans for about 170 hydroelectric projects, including a tree-felling, tunnelling, and hewing stone plan that makes this region a rabbit warren.

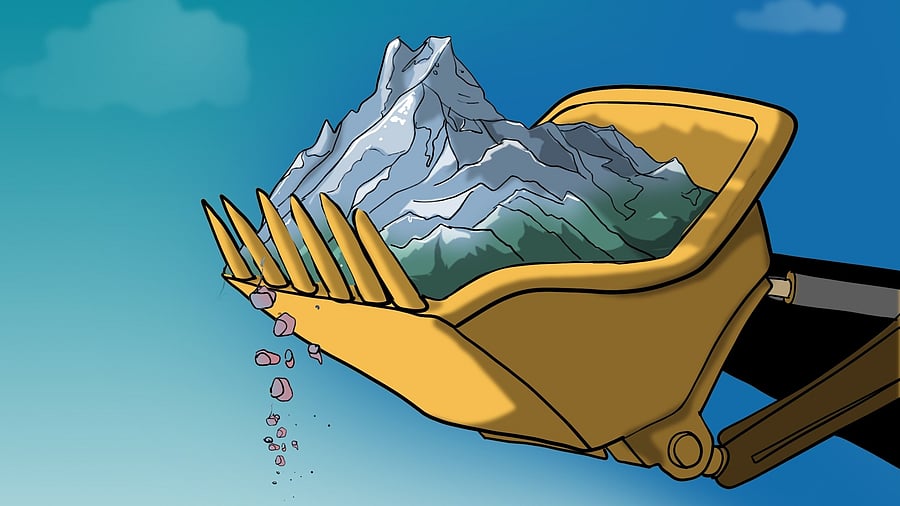

The pictures from Meghalaya tell us that India is surely chipping away at her northern hills, boulder by boulder. The mines of Assam and Meghalaya provide petroleum and natural gas reserves, coal, limestone, and precious uranium in the Khasi hills. The north-eastern states have ambiguous mining policies and regulatory hurdles that have led to unchecked corruption and environmental degradation. In Meghalaya, this has additionally resulted in the displacement of the indigenous people, culminating in the National Green Tribunal ban on coal mining.

Meghalaya’s stone export business has been valued at Rs 600 crore, supplying mainly to Bangladesh. Bangladesh has five land ports with Tripura, Meghalaya, and Assam. The import value of these stones is about $10 per tonne, and the export value, especially to Sharjah and Dubai, is $25 or above per tonne. Meghalaya does not have a proper regulatory regime and is governed by the 1952 and 1957 mining acts. The Meghalaya Mines and Minerals Policy, 2012, is yet to be implemented.

‘Stone mining creates a lot of damage. There is a loss of forest, and a depletion of water... it acidifies water’, Down to Earth reports quote Vanashakti director Stalin Dayanand as saying. ‘When you open out the mountains (through mining), you are creating heat islands there… You are contributing to global warming too…. What was a thickly forested mountainous

area with birds and biodiversity has turned into barren land, like a desert…’, according to Dayanand.

Trying to save the Himalayas has proven to be a herculean task, especially for experts like S P Nautiyal, Y K Murthy, K S Valdiya and activists like Sunderlal Bahuguna, who was repeatedly jailed for his protests and died a disappointed and desolate man in 2021. Let us remember his efforts this January.

(The author is a writer on science and environment issues)