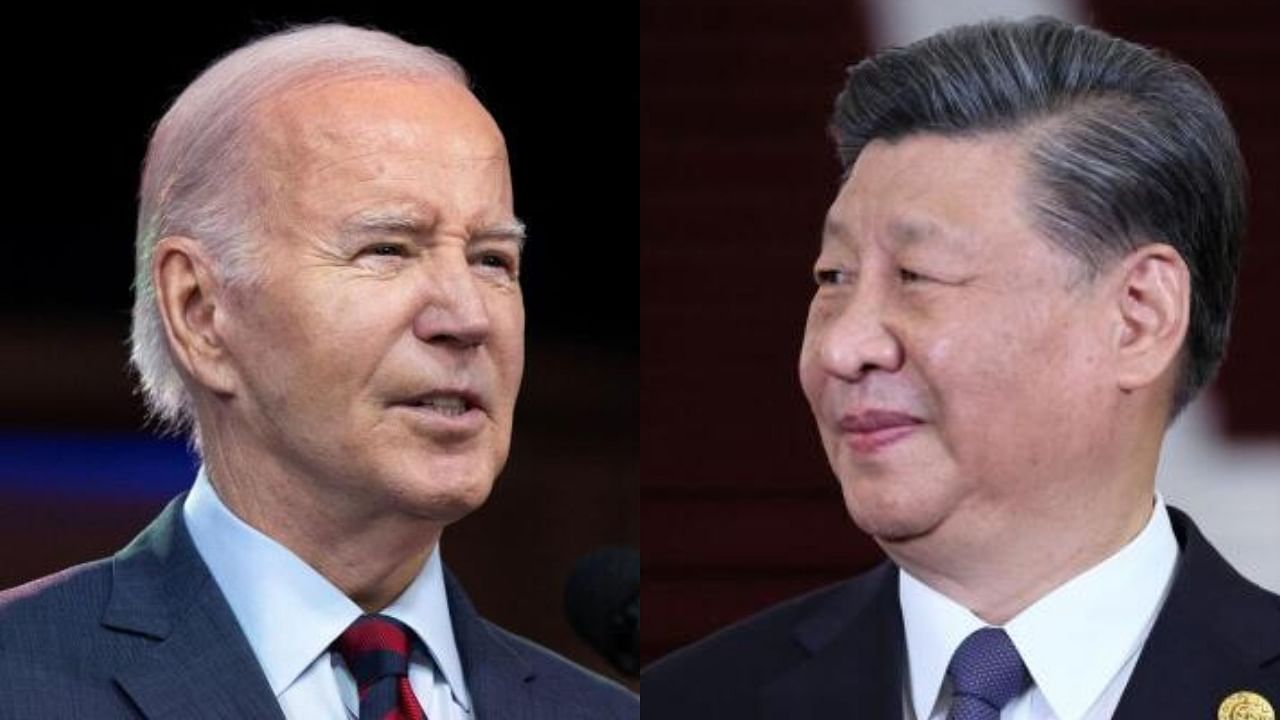

Joe Biden (left) and Xi Jinping (right).

Credit: Reuters Photos

United States President Joe Biden will be meeting his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping at the APEC Summit in California in what will be the latter’s first trip to the US since 2017 when he met with Biden’s predecessor Donald Trump.

In that time, US-China relations have undergone a sea change — for the worse. Trump responded to a series of broken promises by Xi on bilateral and international issues dating back to the Barack Obama presidency by designating China a “strategic competitor” and instituting a series of trade actions against the country.

While the Biden and Trump presidencies differ significantly on almost every domestic and foreign policy issue, most decisions against China taken by the Trump administration have stayed. That said, if a recent write-up on US foreign policy by Biden’s National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan is anything to go by, his administration continues to be hopeful — without foundation — that engagement with China can still work in resolving bilateral and global issues.

While Sullivan acknowledges the geopolitical competition with China, he continues to misunderstand it. To even say, as he does that “there have been encouraging signs that Beijing may recognize the value of stabilization” in ties displays a lack of understanding of how the Chinese political system operates and its view of the US as an existential threat. Xi’s speeches and Communist Party of China (CPC) documents are permeated by concerns about internal stability and threats that apparently emanate from liberal, democratic political systems outside China’s borders. Friendly noises from Beijing can, therefore, only be tactical, not sincere.

In another instance, Sullivan argues that “the two sides need to be able to work together on the risks that arise from artificial intelligence”. He is at pains to declare that “Doing so is not a sign of going wobbly…” But it is precisely that. Sullivan ignores not just the Chinese Party-State’s domestic record on the use of existing high-tech tools in its arsenal to monitor and control its minority and dissident populations, but also the export of such technology to help other authoritarian governments implement similar policies.

Sullivan even has words of faint praise for China brokering the diplomatic deal earlier this year between Iran and Saudi Arabia. He notes that his country “could not have tried to broker that deal, given the lack of U.S. diplomatic relations with Iran” but offers no explanation of why the US cannot return to the Obama-era multilateral deal on the Iran nuclear programme that was scuppered by the Trump administration. Instead, of a concert of powers trying to manage Iran, Washington appears content to cede space to just one power — China — to do the managing. Why that one power could not have been India is a question worth pondering in New Delhi, at least. In the meantime, though, Sullivan appears to be unconcerned about China constraining India’s space in the region.

The US “adjusting for a new period of competition in an age of interdependence and transnational challenges” is a logical mantra, but it is not something that can be implemented by the US and other democracies alone acting in good faith. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and any number of Chinese actions ranging from the South China Sea to the Line of Actual Control with India suggest that authoritarian states do not see value in acting in good faith. Democratic nations are, therefore, setting themselves up for failure by unilaterally promoting engagement and reconciliation.

It is possible that the US believes it does not have the capacity at the moment to counter China full throttle. Sullivan admits as much when he notes, “we need a sustained sense of confidence in our capacity to outcompete any country.” As he notes in his opening paragraph, one of the “the strategic decisions countries make that matter most” is of “how they organize themselves internally”.

Indeed, there are problems in the way that the US has ‘organized itself’. The advantages of “a growing population, abundant resources” that Sullivan declares are overblown if the kind of internal divisions in the US today are anything to go by. The US is “an open society that attracts talent and investment and spurs innovation and reinvention” only in parts — it is also an extremely unequal society with uneven access to knowledge, talent, and innovation within.

This lack of concern with internal inequality has been a major US failure. The Chinese, by contrast, have actively grappled with problems of various domestic inequalities for decades now. Their experience with internal balancing through regional development programmes targeted at their under-developed west and border provinces has informed such external strategies as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Naturally, as an external strategy, the primary goal is to protect and promote Chinese interests; but, while most nations engaged with China understand this as well as the hierarchy involved, they are willing to go along with it because the US has done a worse job of equitable engagement and shared leadership.

The US remains reluctant to participate in an Indo-Pacific trading arrangement like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and ‘Bidenomics’ as Sullivan defines it, is underpinned by protectionism — the US objective is to “sustain its core advantages in geopolitical competition”. Clearly, the US lacks faith in “its alliances and partnerships with other democracies” or is reluctant to share global leadership with them despite Sullivan calling them the US’ “greatest international advantage”.

Taken together, these are the wrong responses to China-led regional and global initiatives such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership or the BRI, and to its efforts to coerce and undermine US partners and allies in Asia.

When he meets with Biden, expect Xi to be aware of these contradictions in US’ policy, and to exploit them accordingly.

(Jabin T Jacob is Associate Professor, Department of International Relations and Governance Studies, and Director, Centre for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi-NCR. X: @jabinjacobt.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.