The fact that complex plants and animals survived all those fluctuations — that extreme temperature swings might even be a normal part of Earth’s history — doesn’t let us off the hook for human-caused climate change.

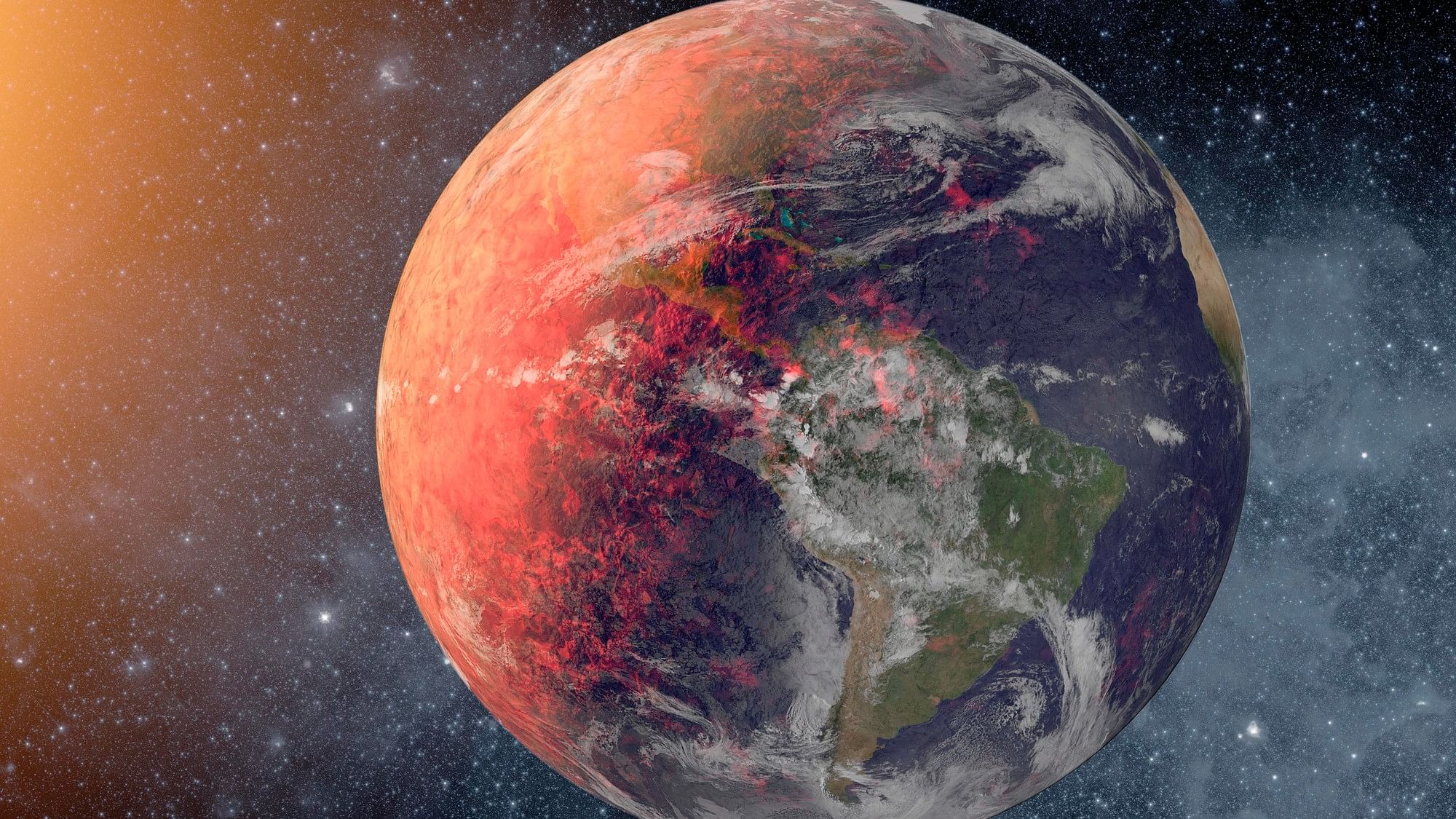

(Representative image)

Credit: iStock Photo

By F D Flam

Scientists have pieced together enough clues to Earth’s past climate to graph the average temperature from 485 million years ago to the present — back to a time long before dinosaurs and even trees, when the land was either barren or hosted mostly moss, millipedes and primitive insects. This new work shows temperatures spent hundreds of millions of years bouncing up and down, from climates similar to ours to ones that were steamier by about 15C (30F).

Earlier attempts to chart our planet’s ancient climate suggested vastly hotter average temperatures — 30C (60F) above today’s — that gradually cooled. The new analysis, published this week in Science, instead shows a series of extreme oscillations but no overall trend.

The fact that complex plants and animals survived all those fluctuations — that extreme temperature swings might even be a normal part of Earth’s history — doesn’t let us off the hook for human-caused climate change. Our current climate crisis is unfolding too quickly for many species to adapt. There were similarly abrupt temperature upswings millions of years ago; the result was mass death.

The new research covers a period called the Phanerozoic Eon. The name is derived from the Greek for visible life. It marked the period when living things left fossils of shells and later bones, wood and leaves. The fossils show a time of dramatic changes. Around 375 million years ago, fish dragged themselves out of the water on proto-limbs to become the first land vertebrates. The continents become forested some 350 million years ago, and dinosaurs emerged around 240 million years ago, dying out suddenly 65 million years back.

Looking back over the long course of time can help scientists understand how Earth’s climate works and what factors make a planet habitable. “Very large swings in climate are the norm for this planet, and they have been driven very clearly by changes in CO2 concentration,” said Benjamin Mills, a biogeochemist at the University of Leeds, who wrote a commentary piece on the findings for Science. But the swings have never been big enough to destroy life entirely. Venus, by contrast, might once have been temperate but got hotter and hotter until it was an uninhabitable blast furnace.

Knowing how Earth’s temperature behaved deep in the past can also help scientists test climate models that predict the future. “The only way we can test if these models can actually properly represent what happens when climate gets hot is to compare them to these examples from the paleo record,” said Mills.

The new analysis shows Earth repeatedly jumped between a sweltering 30C state, known as a greenhouse, and the cooler state, around 15C, known as the ice house. “Right now, we’re actually in an ice-house Earth,” said Jessica Tierney, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona and a co-author of the paper. Our average temperature is around 15C and, for now, we still have thick ice on Greenland and Antarctica.

She and her colleagues created the new graph using a combination of clues. The most important comes from the ratio of ordinary oxygen to its heavier isotope, called oxygen 18. The amount of oxygen 18 incorporated into minerals and fossils depends on temperature. Any given sample will record a local temperature, but with enough samples from different latitudes, it’s possible to estimate a global average.

Scientists long knew about past hot spells from the fossil record, which showed that crocodiles had once roamed the Arctic and palm trees thrived in Antarctica. That record also shows periods where the diversity of life suddenly collapsed.

The worst mass extinction event happened about 250 million years ago, when an estimated 70 per cent of land species and 90 per cent of marine species were snuffed out. The primary culprit was a series of volcanic eruptions that caused carbon dioxide levels to spike. Another paper published earlier this month in Science re-examines that deadly hot spell and attributes some of the dying to a tipping point in ocean currents, like a giant El Nino event that accelerated the rate of heating.

It wasn’t the extent of the heat that wiped out species. Life’s diversity can flourish in a climate 15C hotter than it is today. The die-offs happen when the Earth’s temperature changes too rapidly for organisms to evolve and adapt — as is starting to happen now.

The one small reassurance is that average temperature, even in the worst of times, never gets much above 30C (86F) or below 10C (50F). The scientific explanation involves feedback loops. A warming Earth is ice-free and much wetter, exposing more rocks. Over hundreds of thousands of years, those rocks weather, a process that sequesters carbon dioxide and cools the planet. As it gets colder, ice covers those rocks once again, the rock-weathering stops, and atmospheric carbon starts to build up once more.

That cycle is keeping our planet alive and will continue to do so for millions of years, though it won’t do anything to save humanity from the trouble created by our carbon emissions. We’re already seeing other species pushed to the brink by human activity, from polar bears to coral reefs to wild salmon. The next half a million years might be in the hands of Mother Earth, but the coming decades are in ours.