By Ruth Pollard

Tens of millions of women have disappeared from the workforce in India over the last decade. That’s before Covid-19 worsened female employment prospects by displacing another 6.7 million from their jobs. So how did India — which until the pandemic hit was one of the world’s fastest-growing large economies — fail to increase women’s participation in line with that expansion?

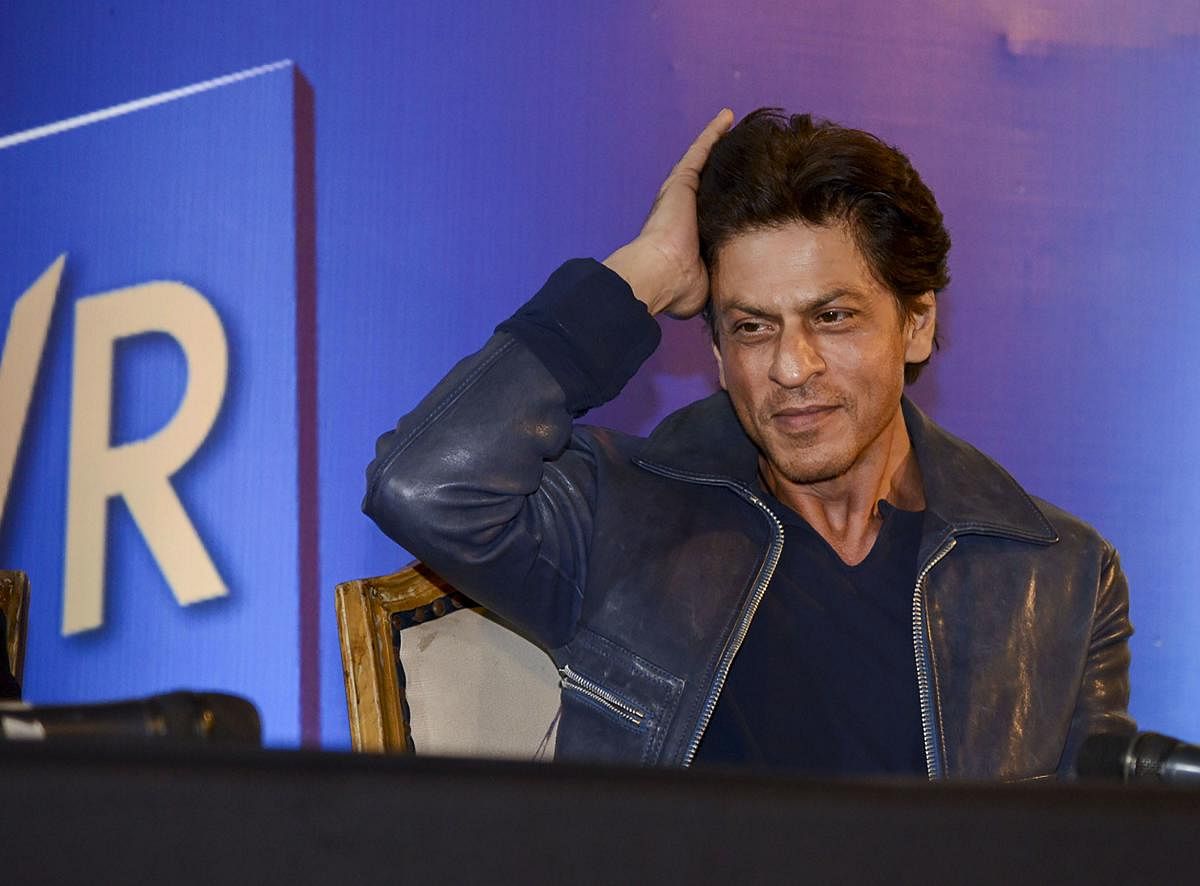

In a new book, economist Shrayana Bhattacharya has used the career of Bollywood leading-man Shah Rukh Khan to emphasize the barriers that prevent women from stepping outside the home and into the workplace. They include safety concerns, family pressures, the burden of housework and inter-generational care, and chronic underinvestment in child care. Khan, whose fame extends far beyond India to South Asia’s vast diaspora and into the Middle East and North Africa — he even has an orchid named for him in Singapore — exhibits freedom of choice and movement that women can only dream of. As Bhattacharya writes in “Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh,” women don’t want to marry Khan. They want to be him.

A Bollywood fixture for 30 years, Khan mostly plays the outsider in love stories — taking on fragile, vulnerable characters worried about finding happiness and avoiding the standard hyper-masculine tropes of Indian cinema. In real life, he’s been married to his high school sweetheart — a Hindu — for three decades. As a Muslim, he’s repeatedly spoken out about “extreme intolerance” in India and received an award at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2018 for his work on women’s and children’s rights.

Even expressing love for his films is a form of protest for poor and working-class women, Bhattacharya notes. This is a country where the entire conversation about the economy, how it will grow and in which direction, is still largely dictated — and dominated — by men. The focus is on the market, and the market is outside the home. “The economy isn’t just a bunch of us trading money; it is a whole range of interactions and if women aren’t allowed to leave home, how can they participate in that market?” she said.

There is, she says, shocking inequality between men and women in today’s India. Despite rapidly increasing educational attainment for girls along with declining fertility, a 2020 World Economic Forum report placed the nation in the bottom five countries, with Pakistan, Syria, Yemen and Iraq on gender gaps in economic participation. In 2021, the WEF further laid bare the disparities. Just 22.3 per cent of Indian women participate in the labour market, translating to a gender gap of 72 per cent. That compares with Turkey (38.5 per cent women’s participation, 50 per cent gap), Mexico (49.1 per cent and 40 per cent), Indonesia (56 per cent and 33 per cent).

Men cornered most of the employment gains in post-liberalization India, where households that managed to move into higher income brackets took on more conservative values, forcing women to leave their jobs and return to the home full time, Bhattacharya said.

For all of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s programs to foster women’s empowerment, including a financial inclusion scheme encouraging them to open bank accounts and the provision of cooking gas and toilets in rural areas, the reality is that not much has changed under his seven years in power. Until women can safely commute to work and then do their jobs without fear of harassment, they’ll remain shut out from large parts of the economy. Their place outside the home must be as valued as inside of it.

Women’s physical movements are constantly policed in India, particularly in the more conservative and densely populated north, home to the capital, New Delhi. It’s not unusual to visit a village in the populous, Hindi-heartland state of Uttar Pradesh and struggle to find a woman to speak to, and certainly not without a man present. Instead, women are cloistered in the home, where 66 per cent of their labour goes unpaid. This work contributes 19 trillion rupees ($252 billion) to the economy, which, Bhattacharya writes, is “built by the money men make and trade held together by the invisible love and unpaid care women offer.”

Even as India’s economy grew at an annual average of 7 per cent between 2004 and 2011, the share of women in the labour force fell to 32.6 per cent before hitting a historic low of 23.3 per cent between 2011 and 2017. All this comes at a cost. As Bloomberg previously reported, India could increase its gross domestic product by $770 billion by 2025 by getting more women to work and increasing equality, according to data from McKinsey Global Institute.

So Modi’s big message to global investors — that India is open for business — should be treated with caution. Yes, there are tax incentives for manufacturers and other opportunities, but firms should be aware: If they employ locally, they will mostly be employing men. Any woman on staff will likely have to navigate a complex web of family permissions and other restrictions to make it onto the payroll. Chances are the company will have to provide a special bus or taxi service to ensure a safe commute to work, and there is no established culture of workplace-based child care to help parents manage their family responsibilities.

India’s state-run enterprises are already way behind global counterparts when it comes to environment, social and governance scores, which now play an increasingly important role in guiding investment decisions. According to S&P Global, companies are under pressure to increase the representation of women on corporate boards and in leadership positions and to provide equal compensation and career mobility for women and people of colour.

Through that lens, it’s difficult to see how investing in India is an attractive prospect for firms that care what their shareholders think.

There may well be a post-pandemic economic recovery underway and India could play a larger part in global value chains, but it’s clear women won’t benefit from this shift. They were badly affected by pandemic job losses and, unlike their male counterparts who’ve mostly gone back to work, women account for half of all those forced out, and kept out. That’s despite the fact that they were less than a quarter of the pre-pandemic workforce, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

We should look at these numbers and weep, Bhattacharya said, and yet there are no protests in the street pressing for change. Yes, the percentage of women turning out to vote in state and federal elections has increased and is now on par with men’s, but it hasn’t moved the needle either inside or outside the home.

So where does Shah Rukh Khan fit in?

Our economic lives and romantic lives are closely intertwined, Bhattacharya notes, and Khan’s films provide women with a different life to aspire to: one where they are free to do what they want and where men will treat them with respect, share the load of caring for a large, multi-generational household, and acknowledge that they, too, need to go out and have fun. To buy their own movie ticket and go to the cinema in a country where a significant percentage of women aren’t allowed to leave the house and visit the local market alone.

That means having some economic power and the independence to spend it. Most women, especially those in the vast hinterland where 65% of people live, are still a long way from Khan’s Bollywood fantasy.