In his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, the conservative British parliamentarian Edmund Burke famously wrote that in several languages -- Greek, Latin, French and English -- there are words like ‘étonnement’ (French) or ‘astonishment’ (English), which denote both fear and wonder. In other words, the source of fear and awe, etymologically and otherwise, are often the same. This leads Burke to point out that “those despotic governments which are founded on the passions of men, and principally upon the passion of fear, keep their chief as much as may be from the public eye. The policy has been the same in many cases of religion.”

This is one of the key legacies on which the architecture of power is built in modern societies, and where functioning democracies tend to slide, or err, on the side of despotism. This is to say that astonishment and fear, too, narrowly start to co-reside in the sovereign figurehead, a position which in ancient societies was reserved for the most revered of deities. This idea is, in fact, startlingly close to Tagore’s play Red Oleanders, where the king is a voice of disembodied authority, who remains hidden throughout, and without tolerance to the faculties of light and laughter. Between Burke, Tagore and French philosopher Michel Foucault’s influential thesis on power, it is now well-known that the further the source of sovereign power resides, the more momentous is mass astonishment, and consequently, fear.

The history of Narendra Modi in power mirrors this process to the last syllable. In the run-up to the polls in 2014, when Modi was ‘made ready’ for ‘national politics’, one of the planet’s largest and costliest PR exercises was undertaken, after which a starched, sanitised, detoxified Modi emerged from an apparent political vacuum and enchanted a disenchanted polity. There was also a reconstruction of an obscure childhood, in which Modi was gifted with the hyper-masculine powers of a folk-hero, including hunting down a crocodile. Since coming to power, therefore, Modi has ensured that he exists in a costumed, choreographed distance, from both the polity and the people, emerging only in modes of instruction where his person cannot be probed. In fact, Modi has embodied the idea of a pontiff-like reverend, who would appear sparingly at epic distances, visualised against photogenic landscapes, sprinkle holy water on hopes, sermonise about life’s hurdles, deliver homilies about national security, and then vanish into the elaborate superstructure of power. Religion and nationalism were natural allies in this elaborate rhetoric of engineered reverence, or as Burke would say, fear.

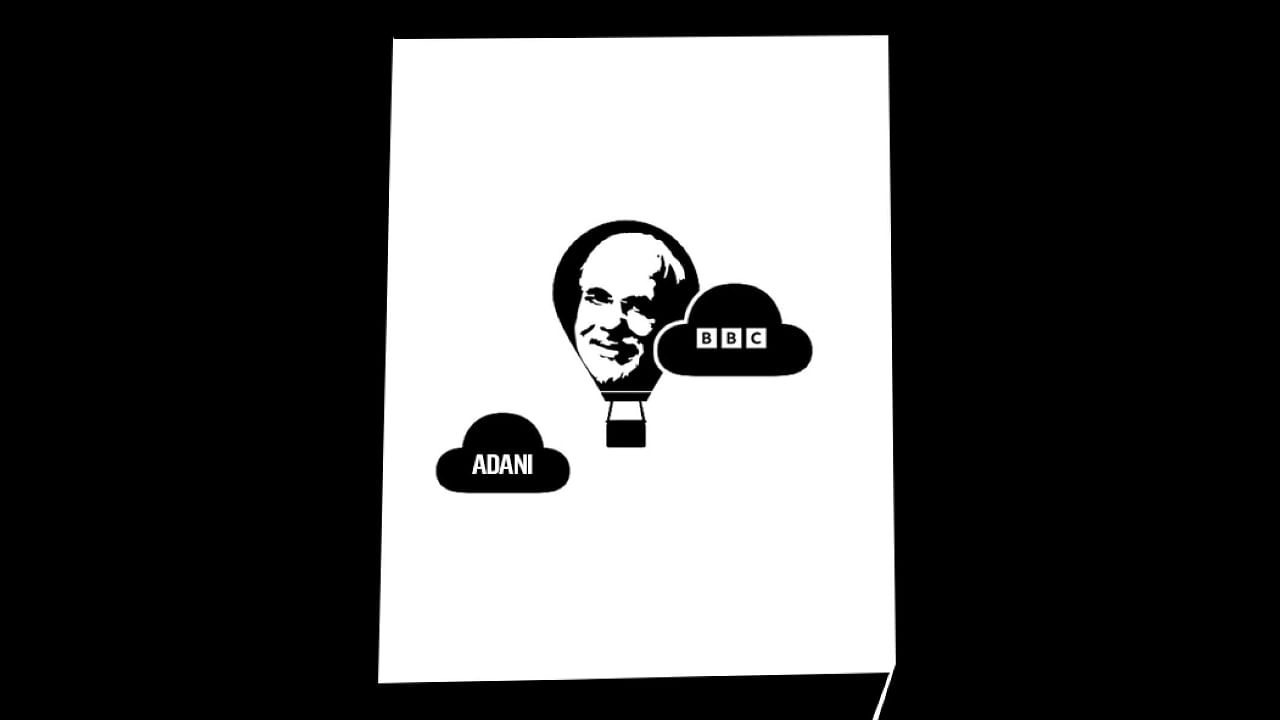

This is not new, but it is relevant again. There has been a lot of debate about why the Modi government banned the two-part BBC documentary India:The Modi Question that surfaced in the middle of January. The documentary is about a much-debated and recorded act of majoritarian rioting in Gujarat in 2002, admittedly in reaction to a dastardly attack on a train carrying Hindu kar sevaks in which 59 of them died, when Modi was Chief Minister of the state. The current government called it propounding a “discredited narrative” and accused the film of being biased against a popular leader of a democratic country. But that was not the end. India’s taxmen then raided the BBC offices in Mumbai and New Delhi. So, the question persists, what is Modi so afraid of about the documentary?

If we look deeper into the psychology of censorship, we see that what the film did, among other things, was to have punctured the laboriously manufactured image of Modi as a clean leader, bringing back to public memory the background of his rise to prominence and power. What the government fears is the impact the documentary would have on his carefully constructed image post-2002 if it were seen by today’s youth, who do not know or remember what happened in 2002. The film reclaimed the impression that Modi’s rise to prominence was paved through a history of violence, chants of hatred against the minorities, and dog-whistling. In other words, the documentary acted as a leveller, bringing down Modi to the level of the foot soldiers of Hindutva, who routinely ravage vulnerable minority neighbourhoods in India’s populous northern parts.

This became clearer when Modi’s cheerleaders failed to answer why the government banned it with such haste. What they avoided was this conundrum: if the film was to be taken seriously, then Modi would be seen as having been at least negligent, if not complicit or even an enabler of the Gujarat riots; if he was to be held blameless, then one had to explain how such a calamitous episode could unfold when he was helming the state. So, accepting the film would have left Modi’s apologists with two options: to either see him labelled as a riot-enabler, or as an incompetent administrator. Both these possibilities, once acknowledged across the world and whitewashed subsequently, were in real danger of resurfacing. Now, the raid on the BBC has only deepened the conundrum.

Along with the image of the powerful leader, whenever he is cornered, Modi has not let go of an opportunity to project himself as one more sinned against than sinning, and has continued taking refuge in melodramatic distractionism. He has done the same lately in parliament, too, completely ignoring questions about the BBC film and the Adani saga and his proximity to the billionaire. This whole performance of being the strong leader one day and a crying, perambulating, helpless baby the next is part of Modi’s elaborate pantomime of power. So far it has worked with part of the gullible public already swayed by hate and partisan evangelism. The question is, how much longer?

(The writer is an academic and author. Views are personal)