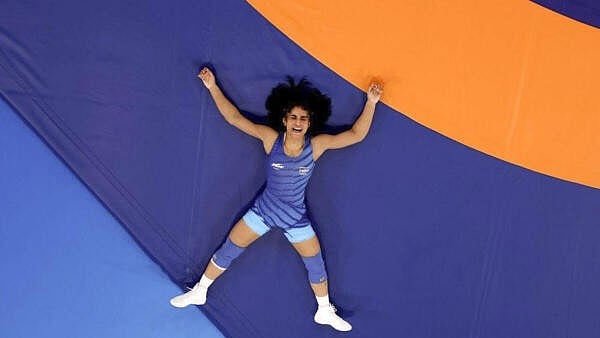

Wrestler Vinesh Phogat

Credit: PTI Photo

By Palash Krishna Mehrotra

Everyone hoped against hope that Vinesh Phogat would win by a whisker, what she had lost by a whisker. Eventually, it was not to be. The sole arbiter’s CAS (Committee of Arbitration in Sport) ruling was like an Indian train running late, with constant delays and new arrival times being announced.

Never has this nation of a billion obsessed as much about 100 grams. It’s only in sports that so much hangs on so little. It’s like threading the microscopic eye of a very fine needle, after the size of the eye has been halved, then quartered.

In the age of hyper-precision, ‘wafer-thin’ doesn’t even begin to describe it. Wafer-thin is analogue in digital times, when it’s normal to win races by 1/1000th of a second.

In the last track and field event of these Olympics, the women’s 4x400m, the US quartet missed out on the world record (set by the Soviet team, back in 1988) by a 10th of a second. If you miss the train, you miss the train. There’s no chance of running and hopping on, as the train leaves the platform. There’s no room for unnees-bees.

I wonder what happened in the inaugural edition of the 1896 Olympics in Athens, Greece, when everything was decided by the naked eye. In some roundabout way, it reminds me of the first economics class back in school, when we were taught that the subject is both an art and a science. Ditto for sports. Wrestling is an art, but in the way everything is measured to exaction, it’s a science, perverse perhaps, but science nonetheless.

I’m not sure if we learnt anything about the nuances of wrestling or the marking scheme — the basis on which points are awarded. It’s a more complex sport than, say, football, where the only thing a newbie finds difficult to grasp is the offside rule. But weight? That’s a different matter. Every Indian is now an expert on the subject.

Primetime news anchors turned up on national TV clutching a banana, an apple, and a bar of soap. Conspiracy theorists had a field day. Our deep suspicion about weighing has a legitimate source. We grew up in a time when the raddiwala, the veggie seller, and the kirana store guy used stones instead of weights to balance the scale, leading to much suspicion and wrangling.

By now, we know a few solid facts about the lead-up to the weigh-in. The facts lead to questions, some answered, some unanswered.

To get to the facts, one must wade into a swamp of acronyms: UWW (United World Wrestling — the international governing body for amateur wrestling); IOC (International Olympic Committee); IOA (Indian Olympic Association); WFI (Wrestling Federation of India); HC (High Court; three were involved: Delhi, Guwahati and Punjab & Haryana); SM (Sports Ministry); AHC (ad hoc committee); BBSS and SS. It was their machinations, delays, and occasional jugalbandi that eventually decided which category Phogat would finally participate in.

The last acronym refers to the tainted former chief of WFI. No need to spell out his name. Everyone knows what allegedly happened. When BBSS’ position was made untenable by the protesting wrestlers, he was replaced by his close associate, SS. The original acronym was simply split into two, like a rain-worm with the same body and two heads on either end, being spliced in half.

We know that in wrestling participants prefer to wrestle in categories lower than their normal body weight, to gain the strength advantage. We know that Phogat’s weight hovers around 56kg, her preferred category to compete is 53kg but the WFI was unrelenting. The trials were cancelled; the quota slot went to someone else (Antim Panghal). It was made clear to Phogat that if she wanted to go to the Olympics, she would have to compete in the 50kg category. Take it, or leave it.

Phogat arrives in Paris, and on Day 1 of the two-day event, she knocks off three opponents. What stunned all of Japan and the wrestling world was her victory over Yui Susaki, who, coming into the Olympics, had lost only three bouts in her career. It was the biggest of upsets in the sporting arena. She then goes on to win the quarterfinal and the semifinal. It was only on the Day 2 weigh-in that her weight exceeded the 50kg parameter. Leaving aside the career-deciding quibble about the 100g, the fact remains that Phogat won three bouts fair and square. So, why were those rounds nullified and Phogat placed at the back of the line?

It’s a point underlined by the great Jordan Burroughs in a post on X. Rules are set in stone for the present, but not for the future. No.4 of his ‘Proposed Rule Changes for UWW’ argues: ‘After a semi-final victory, both finalists’ medals are secured even if weight is missed on Day 2. Gold can only be won by a wrestler who makes weight on the second day.’ Phogat deserved her silver. Burroughs is a respected name in the world of wrestling, having won an Olympic gold and nine medals, including six golds at the World Championships.

That, in a nutshell, is the story. What I want to do now is to take a step back and look at what goes down behind the scenes when an athlete and her support team, involving many professionals, are desperately trying to cut down on weight before an event. The more one researches, the more it sounds like a scene out of a torture chamber in Guantanamo Bay. It’s like pulling a rubberband, and then snapping it back, not once but many times over.

Wrestlers will forsake food, water, and sleep, while exercising continuously. They will wear a sauna suit and work the Exercycle or jog on the treadmill for hours on end. They will sit inside the sauna to squeeze out the last of the water. Any water intake is measured in drops. Now, a muni might be able to pull this off, but they don’t have to exercise vigorously throughout and wrestle in multiple bouts for two continuous days. Jonathan Selvaraj, writing in Sportstar, mentions Phogat’s past bouts: “Very often, Vinesh would black out in the middle of a match. Her eyes would go dark. She would wrestle on instinct. Sometimes she would even win that way.”

Selvaraj describes how she looked on Day 1, the day she made the weigh-in and defeated three wrestlers: “Her skin stretched like paper against her muscles, her eyes were sunken, and her veins were arid.” If you watch again the video of her bout with Susaki, you can see the eyes are glazed yet focused, glinting with intensity; the strength seems to emanate from a supernatural source. The rubberband was intact and taut, not broken or flaccid.

Others are not so lucky. When you are overdosed on diuretics, the threat of dehydration is very real. The athlete is walking a fanatical tightrope. MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) fighters and wrestlers are known to have suffered organ damage, seizures and heart attacks, trying to make the weight cut on the day of the competition. In 2015, the Chinese mixed martial artist Yang Jian Bing passed away from cardiopulmonary failure, caused by dehydration. He was participating in the ONE Championship in the Philippines. The rubberband, you see, can also snap.

Immediately after the weigh-in on Day 2, Phogat fainted and had to be hospitalised. Which brings us to the question, is it all worth it? Where does one draw the line? When does a sport stop being a sport and start becoming an absurd calculated gamble? When a wrestler, just before a weigh-in, has to stick two fingers in his throat to try and puke, shave off his hair, take off all his clothes (a North Korean wrestler did), when they’re literally stripped of all dignity, all this to make the weight cut, we have to ask ourselves: what’s the larger sporting point in all this.

Yang’s death led to some soul-searching. The ONE Championship now conducts urine tests to check for dehydration levels. MMA fighters are now allowed a leeway of 5 per cent when it comes to weight. Similarly, for wrestling, Burroughs, in his tweet, has suggested a ‘1Kg second Day (sic) Weight Allowance’ and ‘Weigh-ins pushed from 8.30 am to 10.30 am.’ We are dealing with human beings here; we must learn to be humane.

The IOA statement issued after the unfavourable CAS ruling underlines this: ‘The matter involving Vinesh highlights the stringent and, arguably, inhumane regulations that fail to account for the physiological and psychological stresses athletes, particularly female athletes, undergo. It is a stark reminder of the need for more equitable and reasonable standards that prioritize athletes’ well-being.’

Fine, it takes blood, sweat, and tears to win a medal, but a sport can’t become a game of life and death. At some stage, common sense needs to take over. It’s also not wholly the fault of those who administrate the sport. Nenad Lalovic, the head of UWW, keeps reiterating: “We want athletes to compete in their natural weight.”

As for Phogat, only she knows what she is going through, mentally, physically, and emotionally. For us, she is a champion, and always will be, in more ways than one; a fighter both in the arena, and in the society she inhabits.

I’m not being patronising when I say that medals and prizes are overvalued by the world. There are several great authors who have never won the Nobel. We tend to fetishise numbers. Remember the time when India got obsessed with Sachin Tendulkar’s 100th 100. It was just a nice round number. If he’d finished his career with 99, it would still have been an accomplished career.

(Palash Krishna Mehrotra is the author of The Butterfly Generation: A Personal Journey into the Passions and Follies of India’s Technicolor Youth, and the editor of House Spirit: Drinking in India).

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.