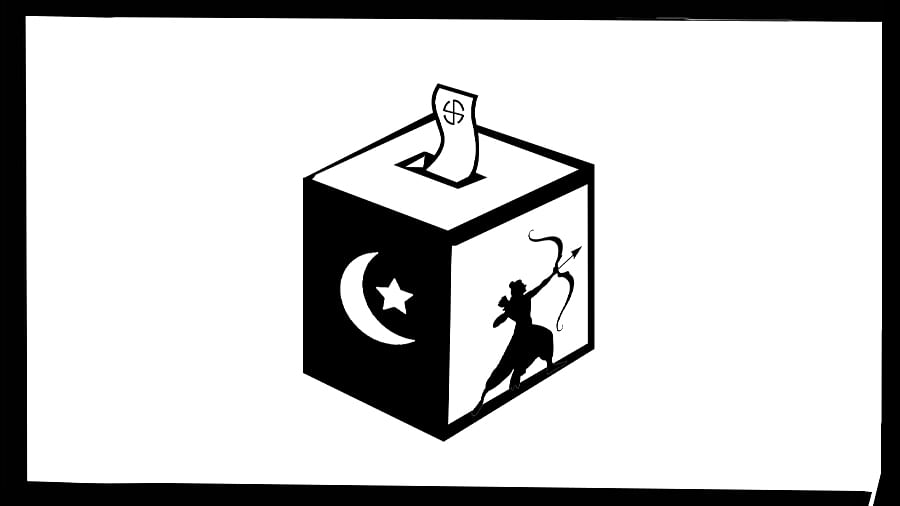

DH Illustration

In the 1950s and 1960s, discussions on developing country politics primarily revolved around tradition and modernity. Newly de-colonised societies were initially perceived as traditional, transitioning towards modernity. This modernity was expected to prize universal values of egalitarianism, identities that prize achievement over ascriptive values, and embracing the freedom of modern liberal democracy over the tyranny of traditions. In India, caste and religion were seen as impediments to this modernity, hindering political progress. However, later, there was a shift in understanding, arguing that traditional categories like caste were being mobilised for modern purposes within liberal democracy. The argument was, ‘How else can liberal democracy be in India, if not in terms of caste?’ However, the theorists of Indian democracy did not extend the same argument to religion because of the specific historical context of Indian democracy emerging amidst partition and communal bloodshed. Thus, the argument was that while it is caste that becomes the force of mobilisation, strengthening Indian democracy, religion, on the other hand, leads to communal politics.

The terms of these arguments have, however, remained relatively constant, while, on the other hand, in India, religion has emerged as a difficult force to comprehend and contend with. The political landscape has evolved from a single-party democracy under the ‘Congress system’ to the single-party democracy of the ‘BJP system’ over the past decade. In the new system, it is not the universal identities of modernity that are aspired to but a narrow caste-less Hindu identity.

The theorists advocating for democracy in terms of caste-based mobilisation now face the challenge of religion-based mobilisation, particularly in northern states where these identities are strong. Caste identities, once targeted for annihilation, have paradoxically strengthened due to decades of Lohiaite caste-based mobilisation by the political parties.

The annihilation of caste did not happen. What took place because of caste politics was the strengthening of the identities of caste. Since these mobilisations were largely of castes within the Hindu fold, eventual mobilisation by religion became easy. The mobilisation from the castes that were not in the Hindu fold often led to the backlash from the so-called upper and middle castes, which again strengthened, instead of diluting, the caste identities.

Governance and development have been ignored altogether in favour of caste mobilisation and caste-based resource distribution, notably in states like UP and Bihar, keeping identities within the traditional narrowness and bigotry. This scenario has facilitated the emergence of the BJP system, particularly in UP.

In the context of modernisation, there was an aspiration for the gradual secularisation of society. Religion was seen as gradually receding into the background as modernisation and modern economic development progressed. The current trend, however, indicates a reversal of secularisation, both in the public and private spheres. The early theorists hoped that in post-colonial societies, the secularisation process would gradually overcome religious and communal politics. That being the case, they hoped that being religious would become as optional as being atheistic. The trends that are blowing, however, are otherwise. The de-secularisation process is not only taking place gradually but is also being presented as the only option. Or de-secularisation ipso facto becomes the only option as the majority of the population finds themselves between the Scylla of identity politics and the Charybdis of neo-liberal economic development. This brings us to another point.

In modernisation theory, with the processes involved, it was hoped that as economic development progressed, other concerns, such as religious identity politics, would become secondary or be relegated to the past. On the contrary, the puzzle is this: as economic development progresses in India, identity politics is surging ahead—both in terms of caste and religion—but the much-aspired universal egalitarian values are not developing.

The paradox is that economic improvement is not making us think in terms of secular values. Instead, economic development is progressing on the one hand, and de-secularisation is progressing on the other. What is the cause of this? The causes for this are to be found in the nature and character of the development process, which sidesteps and marginalises a large number of people, including the middle class, and favours the accumulation of capital in an ever smaller number of people. It is not economic development per se, but rather the nature and character of economic development that need to be examined for an understanding of the phenomenon of the rise of identity politics. In other words, the character of economic development and the nature of the development of identities and identity politics are interconnected. One cannot see them separately. Unequal economic development and gradual de-secularisation are connected realities. The greater the insecurity for ordinary people, the more and more they become de-secularised.

The slogan ‘Aastha aur Vikas’ should better be understood as identity politics because of the nature of economic development. Both of these are reinforcing. The more we are alienated and the more the circumstances appear to be insurmountable, certainly, the more we pray. This is ‘Aastha’ because of the so-called ‘Vikas’.

The early prognostications of the modernisation theory have proven wrong. We are increasingly de-secularized. All traditions are being re-invented by all sections. Today, we remember our ascriptive caste and religious identities more often than we aspire for universalist, egalitarian, and humanist identities. The blame for this rests squarely on the failure of modernisation in the country owing to the extremely unequal development process spearheaded by both the leading parties of the country: the Congress for a long time in the not-so-distant past and the ruling BJP for a decade. The failure of modernisation is not, of course, new; many African and Latin American dictatorships have proven liberal modernisation theory earlier wrong. What makes this special in our case is that we were supposed to be an exceptional case in terms of

our success in modernisation and liberal democracy!

(The writer is Professor of Political Science at the Centre for Political Institutions, Governance, and Development, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru)