Politics often verges on a set of contrasting images. The symbolism is overt and clear. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) today is a settled, established party, and it smells of rhetoric, threat, and sordidness of violence. What threatens it is any sense of agile innocence, idealism, or a fresh sense of competence.

Enter the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) as a political force that projects the search for alternatives, especially through its leadership, with individuals such as Arvind Kejriwal and Manish Sisodia. AAP still projects a semiotic of freshness, of a crusading broom still cleaning corruption. It's still a party that pretends to be hybrid, weaving the protest style of an NGO with the commitment to governance. In local elections, whether in Punjab or Delhi, it has a habit of over-turning the electoral tables, mobilising everyday issues in a creative way.

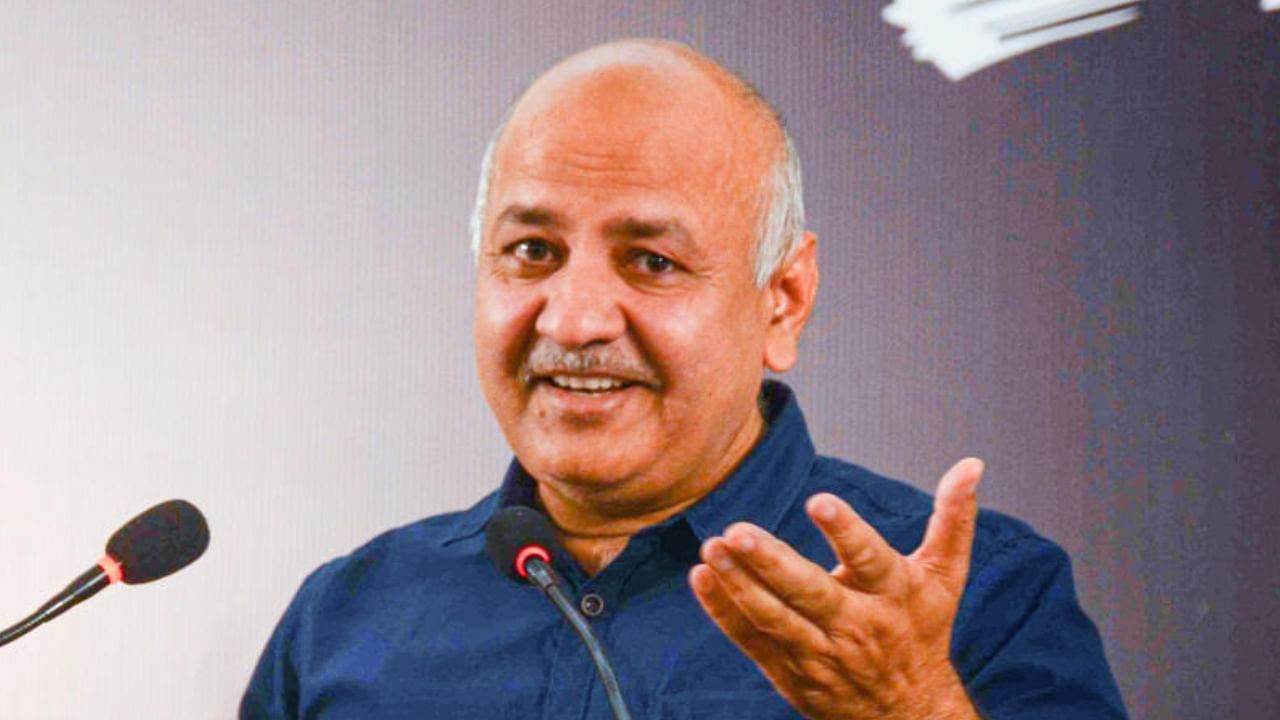

AAP has many outstanding people, but if one man captures this collective style in an individualistic way, it is Sisodia. His is a charisma and competence that exudes a sense of inclusion, and familiarity. His ideas are clear and are articulated superbly in his book on ‘Shiksha’. His views on education go beyond the BJP rhetoric, articulating a sense of plurality and decentralisation. When the BJP beats the drum of patriotism threatening uniformity, Sisodia celebrates decentralisation and hospitality.

His creativity reveals itself in his work on education. The AAP style of education has brought a fresh sense of hope to immigrants and local citizens, creating a new gossip around democracy. Sisodia’s ideas of pedagogy adds a sense of playfulness to the idea of citizenship, creating a vital sense of direct democracy. This quality the BJP lacks, and is openly envious of Sisodia. In that sense he is both a party leader and an exemplar of new ideas around citizenship and education. He contributes critically to AAP imagination of the city and its civics, and has become the focus of global attention. His competence unfortunately makes him a target of rival politicians.

Politics in India has a way of tarnishing ideals, banalizing dreams, and personalities. Corruption is one brush it likes to tar politicians with. As Sisodia gets more experimental and participative, the BJP needed to slow him down. It could not do it with argument and debate, so it decided to muddy his reputation.

The tactics are typical. The Congress used to threaten dissenters with charges of corruption. What was an occasional tool, became a systematic weapon in the BJP’s hands. The smell of investigation haunts many Opposition leaders; in fact, many of them reclaimed their safety and legitimacy by joining the BJP. The list is revealing. It includes Suvendu Adhikari associated with the Sarada chit scam, Mukul Roy accused in the Narada land scam, and Narayan Rane synonymous with the notorious land scam. These politicians became BJP loyalists and found a home in it. The interesting thing was that the BJP uses official machinery to hunt and harass them. Once they switched sides, the threat of investigation disappeared magically.

This is not to argue that Sisodia is above the law. This is to merely ask whether instruments of law can be used to create a fabric of harassment and false charges. The BJP understands that kafkaesque power of investigation. Investigations create all kinds of demands of time and destroy the credibility of a person. The interrogations can be freewheeling, even prolonged. Sometimes even a Doestoyskean interrogator would feel embarrassed in front of a CBI inquisitor, creating a sordidness that threatens electoral possibilities. Sisodia who was heading 15 departments in the Delhi government, will be bogged down by new clerical demands. An efficient politician can be trapped in an investigation machine and come out feeling abandoned and helpless.

What is frightening is that we normalise such evil. The Congress normalised the pathology called Emergency, and turned it into an everyday affair. The BJP has normalised CBI investigations. The simple cry ‘innocent until proven guilty’ sounds naive in a cynical world of politics. In destroying Sisodia’s everydayness, the BJP realises it can tarnish his image of integrity, his evocation of an austere style.

The normalcy with which these rituals of violating are treated make one uneasy about democracy. The signal of CBI investigation often engineered defections across parties. What is corrupt today is the electoral system. Sadly, Sisodia’s experiments in education will slow down and his image as the Santa Claus of education policy will begin demeaning.

Sisodia, in fact, has been co-operating with the investigation, yet he was arrested on grounds of non-cooperation. The issues raised demand an RTI process. It is civil society that must mobilise itself to protect the Sisodias of the world. One has the right to know about the basis of the CBI investigation, it is almost as if investigative agencies are no longer part of the law, but a whimsical network following the tantrums of ruling party politicians. Civil society cannot afford to remain silent.

The Opposition letter to the Prime Minister strikes the right note at an overt level, but it is more like correcting table manners. The covert implications of using probe agencies of collecting dirt needs a deeper framework of understanding. Is Indian democracy ready to confront the politics of witch-hunting?

Shiv Visvanathan is a sociologist, and professor, OP Jindal Global University.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.