The belligerence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s MPs against Congress leader Rahul Gandhi is not letting Parliament function. This is unprecedented, and especially galling because Parliament needs to pass the Budget in this session, irrespective of whether Gandhi apologises for comments made in the United Kingdom on the erosion of democracy in India.

Forget his allegation that the presiding officers switch off the microphones of Opposition leaders in Parliament, by disrupting Parliament for a week it appears that MPs from the Treasury Benches do not want the Opposition to speak at all — giving substance to Gandhi’s criticism.

What is the threat to Indian democracy that Gandhi can recognise — and the BJP does not? Could it be that the BJP sees Gandhi’s criticism — of the partisan capture of State institutions, the misuse of government agencies against Opposition leaders, muting public criticism, compelling sections of the media to turn supine, and the lack of debate and discussion in Parliament — as being undemocratic? Going beyond the idea that they support undemocratic behaviour opportunistically, to efficiently achieve their political ends, it might be asked whether the BJP operates with a definition of democracy that is different from Gandhi’s.

It is conceivable that the BJP rejects the previously accepted definition of democracy — stripping it of its often messy, participatory, and consultative paraphernalia — and instead sees it as an instrument to get elected in order to implement an agenda. The party’s agenda, in this scenario, is equated with that of the people and the nation.

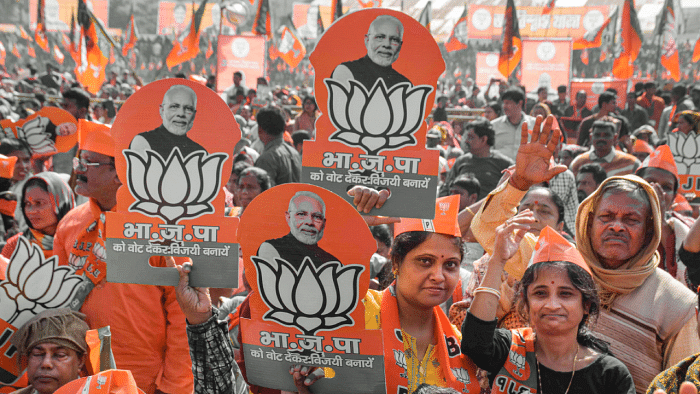

Within this perception, democracy is reduced to merely the electoral process. Once that is mastered, then democracy is about ‘doing good for the people’ with the elected leadership deciding what is good for the people. In other words, a ‘man-of-action’ elected with a sizeable majority, built up as a larger-than-life figure, must be allowed to do his job without let or hindrance. This is because apparently 1.3 billion Indians stand behind him (brushing aside the inconvenient truth that a little more than one third of the voters may have ensured his electoral victory). The BJP rationalises this notion of democracy by showcasing its ‘efficiency’ from delivering on government welfare programmes to building a Ram temple at Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh.

Parliament is needed in this framework only for legislative enabling. The party’s huge majority means that legislative changes can be approved amidst all the din and noise by a voice vote, and claim that they have been approved by Parliament. Thus, for example, 47 per cent of all Bills in Parliament between 2007 and 2017 were passed without debate, and in the Monsoon Session of Parliament in 2021, 20 Bills were passed either without any debate or with only the Treasury Benches speaking on the legislation.

Despite some sessions of Parliament showing the promise of debate and discussion, the general trend is towards rushing the legislation through without adequate scrutiny. This allows the BJP to claim that it stands for an effective democracy which enables governance and anyone who questions it — or does not see it democratic — is a threat to a well-oiled democracy.

The side-stepping of accepted notions of democracy does not mean that the BJP is for democratic reforms. In fact, it has made democracy and its functioning opaque by introducing anonymous electoral bonds, and reducing Parliament to a nominal role as the ratifier of enabling laws. That is why it cares little for the relative openness of India in the pre-2014 period which witnessed a free press, lively legislatures, the proliferation of active civil society organisations, trade unions, and the flourishing of ‘argumentative Indians’.

This is why the BJP cannot understand why globally Indian democracy is being downgraded by those who claim to rate democracy, freedom of speech, protection of human rights, religious freedom, and media freedom across the globe. Its response to criticism from abroad and from internal ‘enemies of the nation’ is that India should create its own rating mechanisms.

Hindutva proponents trace the existence of democratic institutions and structures to ancient times — from village self-governments and even Harappa to the ganarajya of Kalinga before Ashoka’s invasion. It is not a minor peeve but a deep-seated belief among Hindutva ideologues that Hindu India’s heritage which comprises a vast intellectual and political tradition is being sought to be undermined by questioning its democratic credentials.

At the core of this perception of Indian democracy for the BJP is the figure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. For his supporters, Modi is on the path to realising the myth of a formidable India which the world will eventually respect. The sort of Hindu king eulogised by Hindutva texts who holds together the various states of India. Modi represents the strong centre who has expanded its unquestioned authority to the minority-inhabited erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir (by diluting the provisions of Articles 370 and 35A) and by the party’s expansion into the Christian-dominated North-Eastern tribal states of India. It would be a mistake to see the BJP’s willingness to form post-poll alliances with regional political parties in the North-Eastern states only as political opportunism. It is viewed by the Hindutva ideologues as an essential process of integration and assimilation of non-Hindu communities on India’s geographical periphery, just as in the case of J&K.

For the creation of a Hindu India of its dreams, the BJP does not want the Prime Minister to be ridiculed or diminished in any way. That is why the State today demands and rewards loyalty and considers it necessary to punish those who dare to differ with or criticise Modi. With the folding of the Indian State into the persona of Modi as somewhat akin to a Chakravarti (King), questioning the state of Indian democracy is seen as lèse-majesté, an offense against his dignity being an offense against the State itself.

That is why Rahul Gandhi is described as ‘anti-national’, and sought to be expelled from Parliament.

(Bharat Bhushan is a senior journalist.)

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.