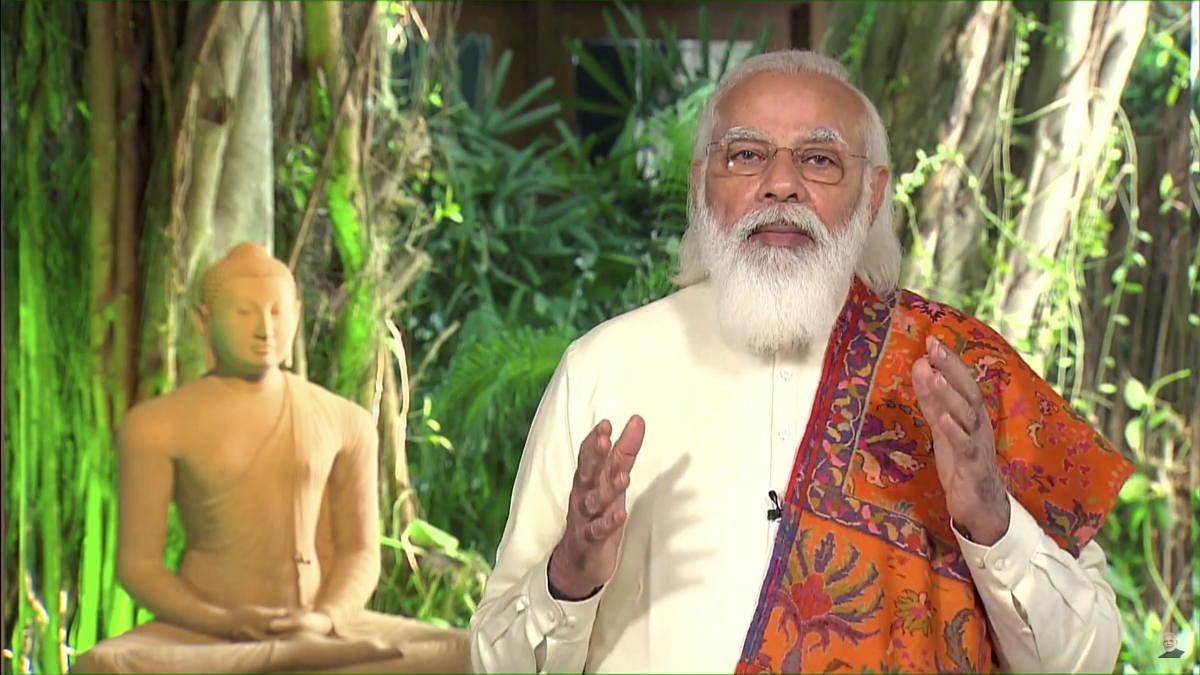

Among the lingering images of 2020 are that of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a new sage-like appearance, complete with a free-flowing but well-groomed beard and hair almost touching his shoulders. It was first noticed within weeks of the nationwide lockdown at the end of March and taken as a sign that Modi too was maintaining physical distance. But by June it was evident that the change of appearance was a conscious act.

In August, after he performed the Bhoomi Pujan for the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Congress leader, Shashi Tharoor, in a TV interview, expressed disapproval at, what he contended, was “appropriation of religious imagery, conflation of the religious and the political.” The Congress leader also decoded what Modi might be attempting with his new look. Modi, according to him, was projecting himself as a “rishiraj”, or “the holy man who is also the king”, the “sage who is also the warrior.” Significantly, in his pithy observations, Tharoor reminded people of Modi’s selective donning of diverse identities. He pointed out that the PM has worn every headgear except the Muslim skullcap.

While there is undoubtedly an element of plain political symbolism in what Modi is attempting – Modi’s new ‘pious’ look makes no bones about his Handiness – there appears to be something more complex at work in this particular recasting of the Modi image, or Brand Modi. There is a hint and a suggestion about how Modi sees himself vis-a-vis his public role as prime minister within the Hindu scheme of things.

The 70-year-old Modi first unveiled this persona of a ‘holy-man-who-is-also-king’ during the 2019 Lok Sabha election. After the end of campaign, but before the last round of polling in crucial states, Modi headed for the Kedarnath shrine with camera persons in his troupe. He spent time meditating at a cave near the temple that had been prepared for his visit.

But this development did not come out of the blue. Modi has often described himself as a wandering mendicant or a “parivrajak”. Having grown up in rural Gujarat in the 1950s, he left home at the age of 17 with the intention of becoming a sanyasi. He had spoken in an interview to me about the influences of sages, mendicants and gurus whose sermons he heard as a child.

But when Modi, the young child, turned up to listen to these shabbily-dressed passing mendicants, he himself would be nattily dressed. An uncle of his told me in his village, Vadnagar, that even when fairly young, Modi was always careful about his attire, taking great care to maintain his (few) clothes. There is little doubt that Modi had an innate sense of image management from his childhood.

This trait continued into his years as a young apparatchik in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). But it was after he became Gujarat chief minister, especially after leading Bharatiya Janata Party to victory in the post-Godhra polls, that Modi acquired a distinctive sartorial stamp, to continue India’s tradition of public figures sporting a signature style.

The Modi Kurta and Modi Jacket emerged in the early years of his chief ministerial tenure, significantly at the time he wooed businesses to invest in Gujarat with the annual Vibrant Gujarat meets. His iconic photo with a Texan hat was an attempt to look ‘different’.

Modi has always tried standing apart from the crowd. He projected himself as a ‘Yugpurush’, someone who comes just once in an eon, an assertion made in the Lok Sabha in August 2019 by a sycophantic BJP lawmaker. The penchant for the extraordinary, the superhuman and the saintly has been typical of Modi’s image.

In January 2015, he infamously wore a pinstripe ‘name suit’ that from a distance was nothing but a classic navy blue pinstripe design. Closer scrutiny revealed tiny letters spelling out the prime minister’s name over and over again. Critics panned this, contending it was indicative of megalomania, but admirers loved it; one even bought it for a staggering Rs 4.31 crore when the suit was auctioned.

Then at the start of his second term as PM in 2019, there was the ‘fearless’ leader of Discovery channel’s Man Vs Wild show with Bear Grylls, that saw a delayed telecast due to the Pulwama terror strike. The show was filmed on the day when the attack took place.

More recently, in August 2020, video footage of the ‘ever-caring and contemplative’ Modi amid peacocks was made available. This happened even as the plight of migrants was still being reported and debated in the media.

Failure to go beyond politics

The end of 2020 saw Modi with a shawl draped over his shoulder in the manner of a respected preceptor or teacher addressing the centenary celebrations of two iconic universities in India, the Aligarh Muslim University and the Visva-Bharati University in Shantiniketan founded by Rabindranath Tagore.

Undoubtedly, Modi’s current image is seen as part of the strategy for the Assembly polls in West Bengal. But what may be seen as a Tagorean look, can also be viewed as a rejigged version of M S Golwalkar, the second Sarsanghchalak of the RSS. He too had a spiritual streak and aspired to become a sanyasi.

While the attempt may be to emanate a sage-like quality of being all-embracing as with the Aligarh University outreach, it’s ironic that Modi positions himself as the leader of those belonging to just one faith, the Hindus. This choice is clearly reflective of his politics and provides a throwback to what he famously told a Reuters journalist in July 2013: “I’m a Hindu nationalist because I’m a born Hindu.” It raises the question that if a majority in a country are Hindu, does the prime minister have to display his Hinduness all the time.

Given the multiple images that Modi has projected in his long public life, the current one is unlikely to be his last. Although it is impossible to anticipate his next persona, the beard and hair trimming (if it ever happens) shall definitely be yet another ‘event’.

(The writer is a Delhi-based author and journalist. His books include Narendra Modi’s biography)