Home Minister Amit Shah’s reported exhortation to scholars to write “history based on raw facts, not opinions and views of those who write it” is bang on the mark. He also observes that writing of history should be a “public-driven exercise” (not clear exactly how this works) and not based on the desire or directions of the government.” One can hardly dispute this, especially the latter part of his remarks.

Shah made his remarks on the eve of the launch of the book Maharana: The Crusade of Thousand Years.

It is true that much of the history of a nation, as in our case, is usually written by the victors or colonial masters and there may be much in our history that needs tweaking, retelling, correcting or even overhauling. The only problem is that for millennia, ours has been mostly a word-of-mouth culture. Record-keeping hasn’t been and isn’t today, our strength. That’s why, until as recently as the mid-19th century, we knew very little of our own history.

For example, even the Indus Valley was unheard of, Ashoka was the stuff of myths and legends, the Gupta Empire and much of South Indian history was yet to be discovered; no one kept track even as erstwhile kingdoms crumbled, and the recording of history was the last thing on our mind as a people collectively; certainly not raw, the fact-based unearthing of history. Even today we regularly mix up mythology and history. We treat head transplants (Ganesha), flying (pushpak viman) and atomic power (Brahmastra) in ancient India to be facts because we want them to be facts, not because there is evidence of raw facts.

But let us get a glimpse of what fact-based history could actually mean. Much as it may disturb our sense of nationalism today, it was owing to the passion of two colonial scholars – James Prinsep and Alexander Cunningham -- that we know much of our own history today. Between them, the two pushed our known, evidence-based history back by some 2,000 years.

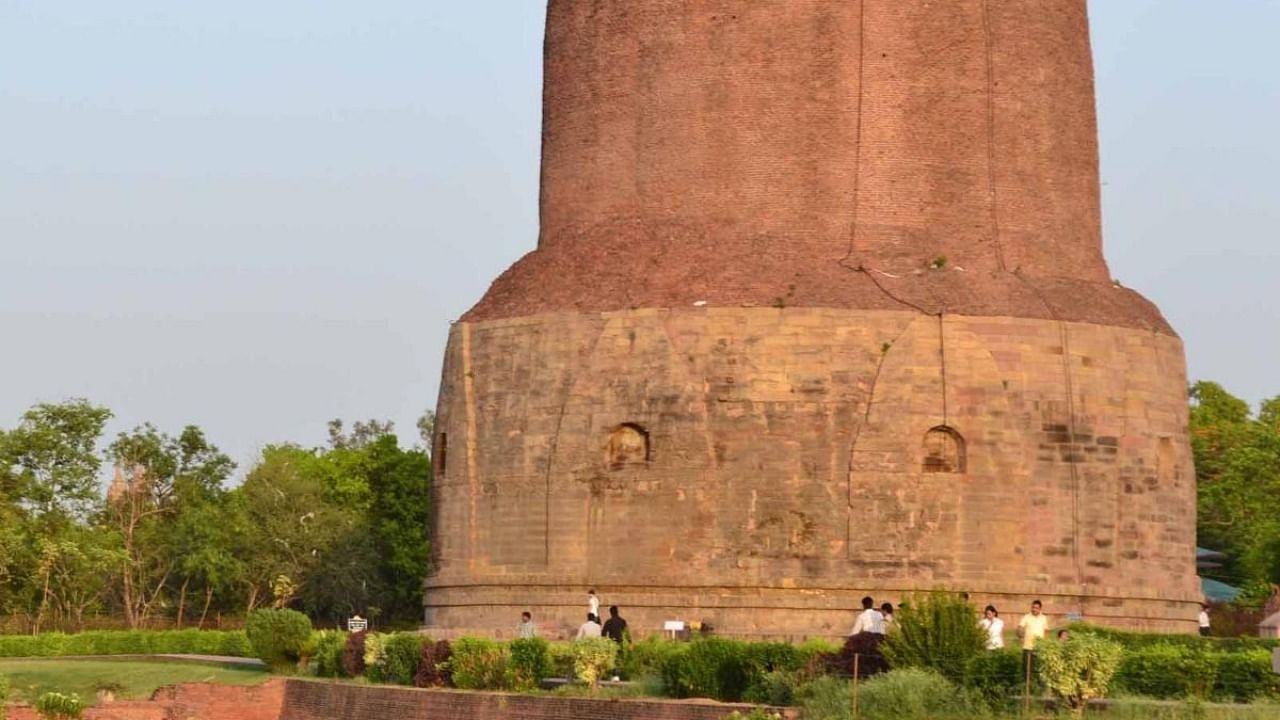

The duo shared their passion for philology and archaeology and collaborated to literally dig into Indian history. They studied coins, seals and other artefacts unearthed during excavations, and their research enabled a historically accurate understanding of various Indian dynasties in some semblance of chronology. Most importantly, their study of ancient inscriptions found on rock faces and pillars, especially those on the stupas of Sarnath, helped decipher the entire Brahmi script, revealing a whole new body of knowledge to the world.

Prinsep published a comprehensive collection of ancient Indian epigraphy in 1877, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, the first volume of which contains the first-ever description of Ashoka’s edicts – comprising 33 inscriptions, etched on a number of pillars, boulders and cave walls. Consequently, it was firmly established that Ashoka of the Mauryan dynasty, who reigned between 269 BCE and 231 BCE, had commissioned these edicts.

The pillars, boulders and caves, representing the early evidence of the teachings of Buddhism, scattered across the Indian subcontinent, from India to Bangladesh to Pakistan and Nepal, more or less proved that Ashoka had taken it upon himself to, almost single-handedly, spread the message of Buddhism across the length and breadth of the land.

We were able to learn from these edicts that Buddhism was evangelised by Ashoka as far as the Mediterranean. Today, if we know so much about Ashoka, we have the facts unearthed by James Prinsep to thank for in large measure.

Similarly, many ancient cities, such as Rajagriha, Sankisa, Shravasti and Kaushambi et al, were identified, thanks to Cunningham’s painstaking excavation efforts. Ashoka’s monolithic capitals, relics of the Gupta and post-Gupta eras, and numerous Buddhist stupas came to light as a consequence, and have now made their way into our history textbooks and tourist brochures. The monastery at Sarnath, where the Buddha first preached Dharma to his five disciples is a prime example. Innumerable inscriptions were deciphered, leading to documentation of Indian history that left no doubt as to the magnificence of her past.

Until Cunningham’s times, King Priyadarshi and Ashoka were opined to be different kings. It was thanks to the works of Prinsep and subsequent excavations by a gold miner, C Beadon, that Ashoka and Priyadarshi, Devanampriya and Ashoka were all confirmed to be one and the same.

One could go on. But my point is to point out that raw fact-finding to bolster history is hard work involving rigorous scholarship and not a matter of mere subjective opinions.

At the same time, proven historical facts need not be discounted merely because those facts come from members of colonial rulers or even a Mughal emperor, especially if their facts and record-keeping were rigorous; all the more because the Hindu tradition was never predominantly a record-keeping tradition – even the scriptures were transmitted word-of-mouth. We have a long way to go to learn about the rigour that raw fact-finding in history can typically involve.

Nor can fact-finding be a ruse to set historical wrongs right. Excavations may show factually that a present-day masjid or church was a Hindu or Jain temple a few hundred years ago, or that a temple today was once a Buddhist monastery, or that a Shaivite temple today was once a Vaishnavite temple or vice versa, and so on. Centuries ago, it was par for the course for one kingdom steeped in one faith to wage war upon another that bowed to a different god, and equally par for the course to destroy their places of worship and replace them with their own. This happened worldwide, not just in India. But in today’s enlightened world (or maybe it is not), such fact-finding cannot be an attempt to undo the wrongs of the past, in the commitment of which wrongs the current generations had absolutely no role.

Rewriting of history texts may well be required, but it has to be hard scholarly painstaking work, and not texts overseen by government servants or driven by public opinion for narrow political gains, which we are in danger of witnessing.

(The writer is an academic and an author)