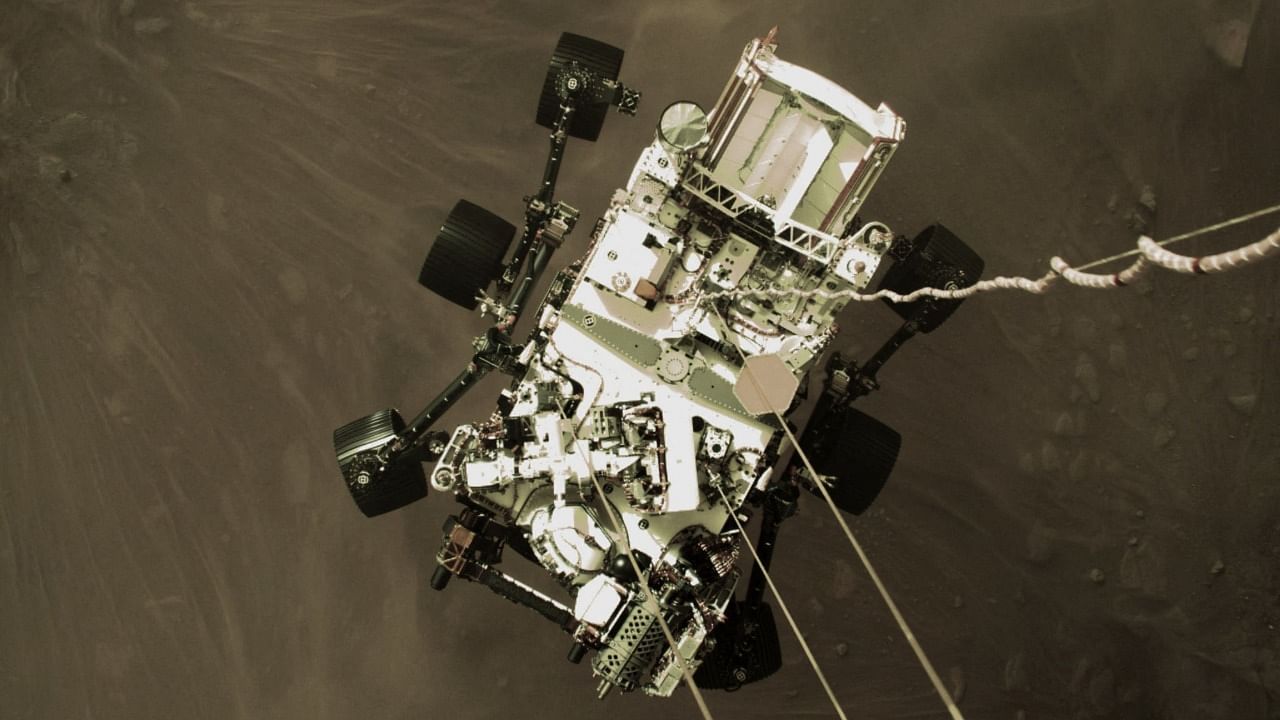

With its impeccable landing on Thursday, NASA's Perseverance became the fifth rover to reach Mars -- so when can we finally expect the long-held goal of a crewed expedition to materialize?

NASA's current Artemis program is billed as a "Moon to Mars" mission, and acting administrator Steve Jurczyk has reiterated his aspiration of "the mid-to-end of the 2030s" for American boots on the Red Planet.

But while the trip is technologically almost within grasp, experts say it's probably still decades out because of funding uncertainties.

Wernher von Braun, the architect of the Apollo program, started work on a Mars mission right after the Moon landing in 1969, but the plan, like many after it, never got off the drawing board.

What makes it so hard? For a start, the sheer distance.

Astronauts bound for Mars will have to travel about 140 million miles (225 million kilometres), depending on where the two planets are relative to each other.

That means a trip that's many months long, where astronauts will face two major health risks: radiation and microgravity.

The former raises the lifetime chances of developing cancer while the latter decreases bone density and muscle mass.

If things go wrong, any problems will have to be solved on the planet itself.

That said, scientists have learned plenty of lessons from astronauts' missions to the Moon and to space stations.

"We have demonstrated on Earth-orbiting spacecraft the ability for astronauts to survive for a year and a half," said Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer for the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

The general ideas of how to execute a Mars mission are in place, but "it's the details" that are lacking, he added.

One way to reduce the radiation exposure on the journey is getting there faster, said Laura Forczyk, the founder of space consulting firm Astralytical and a planetary scientist.

This could involve using nuclear thermal propulsion which produces far more thrust than the energy produced by traditional chemical rockets.

Another could be building a spacecraft with water containers strapped to it that absorb space radiation, said McDowell.

Once there, we'll need to find ways to breathe in the 95 per cent carbon dioxide atmosphere. Perseverance has an instrument on board to convert carbon dioxide to oxygen, as a technical demonstration.

Other solutions involve breaking down the ice at the planet's poles into oxygen and hydrogen, which will also fuel rockets.

Also Read | Kannadathi-US scientist's touch to Mars landing

Radiation will also be challenging on the planet, because of its ultra thin atmosphere and lack of a protective magnetosphere, so shelters will need to be well shielded, or even underground.

The feasibility also comes down to how much risk we are willing to tolerate, said G. Scott Hubbard, NASA's first Mars program director who's now at Stanford.

During the Shuttle era, said Hubbard, "the demand was that the astronauts face no more than three per cent increased risk in death."

"They have now raised that -- deep space missions are somewhere between 10 and 30 percent, depending on the mission, so NASA's taking a more aggressive or open posture," he added.

That could involve raising the permissible level of total radiation astronauts can be exposed to over their lifetimes, which NASA is also considering, said Forczyk.

The experts agreed the biggest hurdle is getting buy-in from the US president and Congress.

"If humanity as a species, specifically the American taxpayer, decides to put large amounts of money into it, we could be there by the 2030s," said McDowell.

He doesn't think that's on the cards, but said he would be surprised if it happened later than the 2040s, a conclusion shared by Forczyk.

President Joe Biden hasn't yet outlined his Mars vision, though his spokeswoman Jen Psaki said this month the Artemis program had the administration's "support."

Still, the agency is facing budget constraints and is not expected to meet its goal of returning astronauts to the Moon by 2024, which would also push back Mars.

Could NASA be beaten to it by SpaceX, the company founded by billionaire Elon Musk, who is targeting a first human mission in 2026?

Musk has been developing the next-generation Starship rocket for the purpose -- though two prototypes blew up in spectacular fashion on their recent test runs.

These might look bad, but the risks SpaceX is able to take, and NASA as a government agency can't, gives it valuable data, argued Hubbard.

That could eventually give SpaceX an edge over NASA's chosen rocket, the troubled Space Launch System (SLS) which is beset by delays and cost overrun.

But not even one of the richest people in the world can foot the entire bill for Mars themselves.

Hubbard sees a public-private partnership as more likely, with SpaceX providing the transport and NASA solving the many other problems.