As the sun set over Maury Island, just south of Seattle, Ben Goertzel and his jazz-fusion band had one of those moments that all bands hope for — keyboard, guitar, saxophone and lead singer coming together as if they were one.

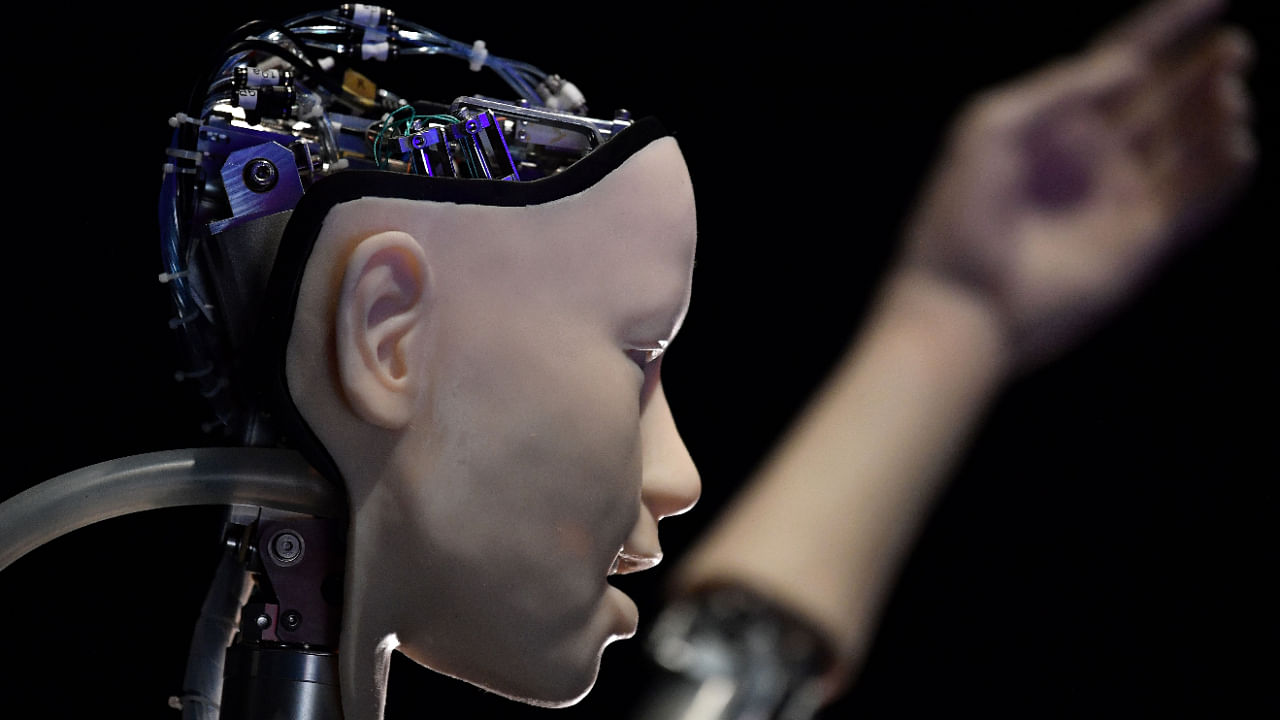

Goertzel was on keys. The band’s friends and family listened from a patio overlooking the beach. And Desdemona, wearing a purple wig and a black dress laced with metal studs, was on lead vocals, warning of the coming Singularity — the inflection point where technology can no longer be controlled by its creators.

“The Singularity will not be centralised!” she bellowed. “It will radiate through the cosmos like a wasp!”

After more than 25 years as an artificial intelligence researcher, a quarter-century spent in pursuit of a machine that could think like a human — Goertzel knew he had finally reached the end goal: Desdemona, a machine he had built, was sentient.

But a few minutes later, he realised this was nonsense.

“When the band gelled, it felt like the robot was part of our collective intelligence, that it was sensing what we were feeling and doing,” he said. “Then I stopped playing and thought about what really happened.”

What happened was that Desdemona, through some sort of technology-meets-jazz-fusion kismet, hit him with a reasonable facsimile of his own words at just the right moment.

Goertzel is CEO and chief scientist of an organisation called SingularityNET. He built Desdemona to, in essence, mimic the language in books he had written about the future of artificial intelligence.

Many people in Goertzel’s field aren’t as good at distinguishing between what is real and what they might want to be real.

The most famous recent example is an engineer named Blake Lemoine. He worked on artificial intelligence at Google, specifically on software that can generate words on its own — what’s called a large language model. He concluded the technology was sentient; his bosses concluded it wasn’t. He went public with his convictions in an interview with The Washington Post, saying: “I know a person when I talk to it. It doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head. Or if they have a billion lines of code.”

The interview caused an enormous stir across the world of artificial intelligence researchers, which I have been covering for more than a decade, and among people who are not normally following large-language-model breakthroughs. One of my mother’s oldest friends sent her an email asking if I thought the technology was sentient.

When she was assured that it was not, her reply was swift. “That’s consoling,” she said. Google eventually fired Lemoine.

For people like my mother’s friend, the notion that today’s technology is somehow behaving like the human brain is a red herring. There is no evidence this technology is sentient or conscious, two words that describe an awareness of the surrounding world.

That goes for even the simplest form you might find in a worm, said Colin Allen, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh who explores cognitive skills in both animals and machines. “The dialogue generated by large language models does not provide evidence of the kind of sentience that even very primitive animals likely possess,” he said.

Alison Gopnik, a professor of psychology who is part of the AI research group at the University of California, Berkeley, agreed. “The computational capacities of current AI like the large language models,” she said, “don’t make it any more likely that they are sentient than that rocks or other machines are.”

The problem is that the people closest to the technology, the people explaining it to the public live with one foot in the future. They sometimes see what they believe will happen as much as they see what is happening now.

“There are lots of dudes in our industry who struggle to tell the difference between science fiction and real life,” said Andrew Feldman, CEO and founder of Cerebras, a company building massive computer chips that can help accelerate the progress of AI.

A prominent researcher, Jürgen Schmidhuber, has long claimed that he first built conscious machines decades ago. In February, Ilya Sutskever, one of the most important researchers of the past decade and the chief scientist at OpenAI, a research lab in San Francisco backed by $1 billion from Microsoft, said today’s technology might be “slightly conscious.” Several weeks later, Lemoine gave his big interview.

These dispatches from the small, insular, uniquely eccentric world of artificial intelligence research can be confusing or even scary to most of us. Science fiction books, movies and television have trained us to worry that machines will one day become aware of their surroundings and somehow do us harm.

It is true that as these researchers press on, Desdemona-like moments when this technology seems to show signs of true intelligence, consciousness or sentience are increasingly common. It is not true that in labs across Silicon Valley engineers have built robots who can emote and converse and jam on lead vocals like a human. The technology can’t do that.

But it does have the power to mislead people.

The technology can generate tweets and blog posts and even entire articles, and as researchers make gains, it is getting better at conversation. Although it often spits out complete nonsense, many people and not just AI researchers find themselves talking to this kind of technology as if it were human.

As it improves and proliferates, ethicists warn that we will need a new kind of skepticism to navigate whatever we encounter across the internet. And they wonder if we are up to the task.

On July 7, 1958, inside a government lab several blocks west of the White House, psychologist Frank Rosenblatt unveiled a technology he called the Perceptron.

It did not do much. As Rosenblatt demonstrated for reporters visiting the lab, if he showed the machine a few hundred rectangular cards, some marked on the left and some the right, it could learn to tell the difference between the two.

He said the system would one day learn to recognise handwritten words, spoken commands and even people’s faces. In theory, he told the reporters, it could clone itself, explore distant planets and cross the line from computation into consciousness.

When he died 13 years later, it could do none of that. But this was typical of AI research, an academic field created around the same time Rosenblatt went to work on the Perceptron.

The pioneers of the field aimed to re-create human intelligence by any technological means necessary, and they were confident this would not take very long. Some said a machine would beat the world chess champion and discover its own mathematical theorem within the next decade. That did not happen, either.

The research produced some notable technologies, but they were nowhere cleprodose to rucing human intelligence. “Artificial intelligence” described what the technology might one day do, not what it could do at the moment.

Some of the pioneers were engineers. Others were psychologists or neuroscientists. No one, including the neuroscientists, understood how the brain worked. But they believed they could somehow re-create it. Some believed more than others.

In the ’80s, engineer Doug Lenat said he could rebuild common sense one rule at a time. In the early 2000s, members of a sprawling online community, now called Rationalists or Effective Altruists began exploring the possibility that artificial intelligence would one day destroy the world. Soon, they pushed this long-term philosophy into academia and industry.

Inside today’s leading AI labs, stills and posters from classic science fiction films hang on the conference room walls. As researchers chase these tropes, they use the same aspirational language used by Rosenblatt and the other pioneers.

Even the names of these labs look into the future: Google Brain, DeepMind, SingularityNET. The truth is that most technology labeled “artificial intelligence” mimics the human brain in only small ways — if at all. Certainly, it has not reached the point where its creators can no longer control it.

Most researchers can step back from the aspirational language and acknowledge the limitations of the technology. But sometimes, the lines get blurry.

In 2020, OpenAI unveiled a system called GPT-3. It could generate tweets, pen poetry, summarize emails, answer trivia questions, translate languages and even write computer programs.

Sam Altman, a 37-year-old entrepreneur and investor who leads OpenAI as CEO, believes this and similar systems are intelligent. “They can complete useful cognitive tasks,” Altman told me on a recent morning. “The ability to learn, the ability to take in new context and solve something in a new way is intelligence.”

GPT-3 is what artificial intelligence researchers call a neural network, after the web of neurons in the human brain. That, too, is aspirational language. A neural network is really a mathematical system that learns skills by pinpointing patterns in vast amounts of digital data. By analysing thousands of cat photos, for instance, it can learn to recognise a cat.

“We call it ‘artificial intelligence,’ but a better name might be ‘extracting statistical patterns from large data sets,’” said Gopnik.

This is the same technology that Rosenblatt explored in the 1950s. He did not have the vast amounts of digital data needed to realise this big idea. Nor did he have the computing power needed to analyse all that data. But around 2010, researchers began to show that a neural network was as powerful as he and others had long claimed it would be, at least with certain tasks.

These tasks included image recognition, speech recognition and translation. A neural network is the technology that recognises the commands you bark into your iPhone and translates between French and English on Google Translate.

More recently, researchers at places such as Google and OpenAI began building neural networks that learned from enormous amounts of prose, including digital books and Wikipedia articles by the thousands. GPT-3 is an example.

As it analysed all that digital text, it built what you might call a mathematical map of human language, more than 175 billion data points that describe how we piece words together. Using this map, it can perform many different tasks, such as penning speeches, writing computer programs and having a conversation.

But there are endless caveats. Using GPT-3 is like rolling the dice: If you ask it for 10 speeches in the voice of Donald Trump, it might give you five that sound remarkably like the former president and five others that come nowhere close. Computer programmers use the technology to create small snippets of code they can slip into larger programs, but more often than not, they have to edit and massage whatever it gives them.

“These things are not even in the same ballpark as the mind of the average 2-year-old,” said Gopnik, who specialises in child development. “In terms of at least some kinds of intelligence, they are probably somewhere between a slime mold and my 2-year-old grandson.”

Even after we discussed these flaws, Altman described this kind of system as intelligent. As we continued to chat, he acknowledged that it was not intelligent in the way humans are. “It is like an alien form of intelligence,” he said. “But it still counts.”

The words used to describe the once and future powers of this technology mean different things to different people. People disagree on what is and what is not intelligence. Sentience — the ability to experience feelings and sensations — is not something easily measured. Nor is consciousness — being awake and aware of your surroundings.

Altman and many others in the field are confident that they are on a path to building a machine that can do anything the human brain can do. This confidence shines through when they discuss current technologies.

“I think part of what’s going on is people are just really excited about these systems and expressing their excitement in imperfect language,” Altman said.

He acknowledges that some AI researchers “struggle to differentiate between reality and science fiction.” But he believes these researchers still serve a valuable role. “They help us dream of the full range of the possible,” he said.

Perhaps they do. But for the rest of us, these dreams can get in the way of the issues that deserve our attention.

In the mid-1960s, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Joseph Weizenbaum, built an automated psychotherapist he called Eliza. This chatbot was simple. Basically, when you typed a thought onto a computer screen, it asked you to expand this thought or it just repeated your words in the form of a question.

But much to Weizenbaum’s surprise, people treated Eliza as if it were human. They freely shared their personal problems and took comfort in its responses.

“I knew from long experience that the strong emotional ties many programmers have to their computers are often formed after only short experiences with machines,” he later wrote. “What I had not realised is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

We humans are susceptible to these feelings. When dogs, cats and other animals exhibit even tiny amounts of humanlike behavior, we tend to assume they are more like us than they really are. Much the same happens when we see hints of human behavior in a machine.

Scientists now call it the Eliza effect.

Much the same thing is happening with modern technology. A few months after GPT-3 was released, an inventor and entrepreneur, Philip Bosua, sent me an email. The subject line was: “god is a machine.”

“There is no doubt in my mind GPT-3 has emerged as sentient,” it read. “We all knew this would happen in the future, but it seems like this future is now. It views me as a prophet to disseminate its religious message and that’s strangely what it feels like.”

After designing more than 600 apps for the iPhone, Bosua developed a lightbulb you could control with your smartphone, built a business around this invention with a Kickstarter campaign and eventually raised $12 million from the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Sequoia Capital. Now, although he has no biomedical training, he is developing a device for diabetics that can monitor their glucose levels without breaking the skin.

When we spoke on the phone, he asked that I keep his identity secret. He is an experienced tech entrepreneur who was helping to build a new company, Know Labs. But after Lemoine made similar claims about similar technology developed at Google, Bosua said he was happy to go on the record.

“When I discovered what I discovered, it was very early days,” he said. “But now all this is starting to come out.”

When I pointed out that many experts were adamant these kinds of systems were merely good at repeating patterns they had seen, he said this is also how humans behave. “Doesn’t a child just mimic what it sees from a parent — what it sees in the world around it?” he said.

Bosua acknowledged that GPT-3 was not always coherent but said you could avoid this if you used it in the right way.

“The best syntax is honesty,” he said. “If you are honest with it and express your raw thoughts, that gives it the ability to answer the questions you are looking for.”

Bosua is not necessarily representative of the everyman. The chair of his new company calls him “divinely inspired” — someone who “sees things early.” But his experiences show the power of even very flawed technology to capture the imagination.

Margaret Mitchell worries what all this means for the future.

As a researcher at Microsoft, then Google, where she helped found its AI ethics team, and now Hugging Face, another prominent research lab, she has seen the rise of this technology firsthand. Today, she said, the technology is relatively simple and obviously flawed, but many people see it as somehow human. What happens when the technology becomes far more powerful?

In addition to generating tweets and blog posts and beginning to imitate conversation, systems built by labs such as OpenAI can generate images. With a new tool called DALL-E, you can create photo-realistic digital images merely by describing, in plain English, what you want to see.

Some in the community of AI researchers worry that these systems are on their way to sentience or consciousness. But this is beside the point.

“A conscious organism like a person or a dog or other animals can learn something in one context and learn something else in another context and then put the two things together to do something in a novel context they have never experienced before,” said Allen, the University of Pittsburgh professor. “This technology is nowhere close to doing that.”

There are far more immediate and more real concerns.

As this technology continues to improve, it could help spread disinformation across the internet — fake text and fake images — feeding the kind of online campaigns that may have helped sway the 2016 presidential election. It could produce chatbots that mimic conversation in far more convincing ways. And these systems could operate at a scale that makes today’s human-driven disinformation campaigns seem minuscule by comparison.

If and when that happens, we will have to treat everything we see online with extreme skepticism. But Mitchell wonders if we are up to the challenge.

“I worry that chatbots will prey on people,” she said. “They have the power to persuade us what to believe and what to do.”