The need to protect various living forms, many of which are disappearing at an unprecedented rate, is often an afterthought in today’s human-centric world. Although our well-being strongly depends on the health of our environment, measures to protect the natural world are met with sluggish actions.

“The only effective way to conserve biodiversity is to integrate conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and human welfare,” says ecologist Kamaljit S Bawa, Founder of Bengaluru-based Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE).

“Beyond local communities, all of us are dependent on services provided by nature such as water, soils, medicines, pollinators, recreation, spiritual enrichment, and so on. Biodiversity is the basis of our food systems and rural economy.”

India, the world’s most populous country, is megadiverse country harbouring about a tenth of the planet’s lifeforms, some of which are not found anywhere else. So how must the county balance protection of biodiversity while ensuring that people get benefited?

In a recent study, a consortium of conservation scientists from various Indian institutes has identified key landscapes across the country that could be targeted for biodiversity conservation while ensuring human well-being. The study, published in the journal Nature Sustainability, is part of the National Mission on Biodiversity and Human Well-Being (NMBHW)—a national initiative to integrate biodiversity conservation with people’s socio-economic development.

So far, India’s protected areas, which constitute less than 5% of the country’s land, are designated based on iconic or keystone species that live there, like tigers and elephants, ignoring the connectedness of ecosystems and their benefits to people. For example, grasslands are considered ‘wastelands’ and aren’t protected. But, they are also home to some endemic species. People depend on it for livestock grazing, cattle fodder and firewood.

“In countries like India, human welfare and economic aspirations are important considerations; as are nature’s benefits to humans,” says Arjun Srivathsa, a wildlife biologist at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bengaluru, and the corresponding author of the study. “These aspects are often ignored while demarcating areas for biodiversity conservation.”

Besides, these protected areas overlap administrative boundaries making it a challenge to implement conservation policies. They are small, often not sufficient to stop or address the loss of biodiversity or benefit people as an ecosystem. “For many wide-ranging species, and for large landscape-scale processes, we need to conserve large swathes of connected areas,” argues Srivathsa.

To identify such landscapes, the researchers aggregated data from various sources on the different habitats and ecosystems across India, including deserts, ravines, open grasslands and rocky outcrops.

Identifying the overlaps

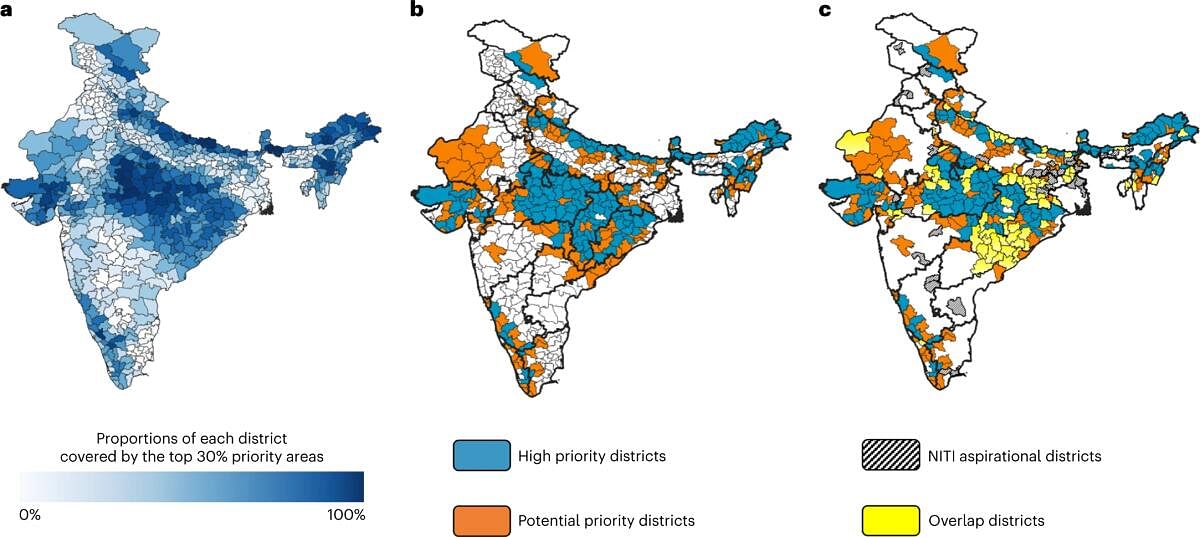

The analysis identified 338 districts across the country as hotspots for optimal conservation. Among them, 169 districts are ‘high priority’ districts where natural habitats, biodiversity and benefits to humans from the ecosystem are optimal and span across a large area, and 72 districts overlap with NITI Aayog’s Aspirational District Programme—an initiative designed to transform 112 most under-developed districts across the country.

Geographically, the 338 districts seem to be distributed across the Western Ghats, the Himalayas, the historically-neglected deserts and semi-arid landscapes of Western India, and in central and eastern India. However, only 15% of the currently-designated protected areas overlap with the identified priority conservation areas.

The final map of priority conservation areas included areas on the borders of various administrative zones, highlighting that landscape conservation needs to consider the ‘connectivity’ of the pockets of land. “Our detailed fine-resolution maps provide information that can be used for extremely localised interventions,” says Srivathsa about the findings. “At the large landscape scale, we can see what land parcels are relatively more important.”

“This study identifies conservation priority areas that represent critical natural habitats, provide crucial ecosystem services and contain a diversity of threatened species and can thus help in evidence-based conservation planning at a landscape level,” says ecologist Asmita Sengupta from ATREE, not involved in the study.

In the ‘high-priority’ districts, the authors suggest that authorities focus on retaining habitats, deprioritising mega-infrastructure projects like dams and highways, and working with local communities to steward the ecosystem outside protected areas. In the remaining ‘potential priority’ districts, conservation can be incentivised by paying communities, promoting agroforestry and restoring ecosystems.

The study’s findings serve as the first step in NMBHW by pinpointing where concrete actions to realise a sustainable future could be taken up. “While it is a good piece of work, it will be important that together, we follow up on ways to implement the knowledge acquired through this collaborative exercise,” says Uma Ramakrishnan from NCBS, the lead author.

In the face of climate change and rapid biodiversity loss, protecting nature to protect ourselves is perhaps a win-win strategy. As the study’s findings show, India’s approach to conservation needs a big rethink. “Our narrative about conservation needs to change,” says Bawa. “Biodiversity conservation is not about a bunch of unique plant and animal species but how we secure our future and of our planet.”