An asteroid hurtling towards the Earth and people scrambling to save humanity from impending extinction is a plot familiar to any science fiction lover.

Early on Tuesday morning, NASA played out this very script in real life, sans the extinction-level threat to humankind.

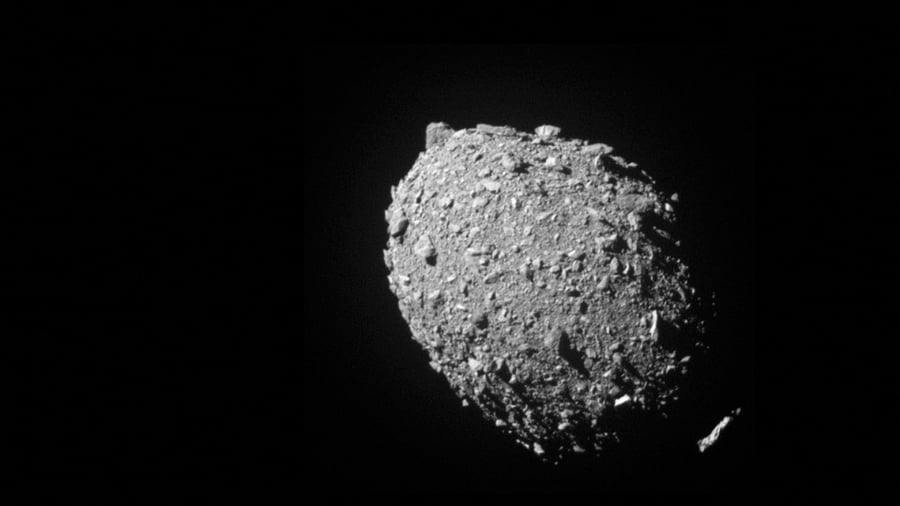

After 10 months in space, NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft crashed into the asteroid Dimorphos, roughly the size of a football stadium, some 11 million kilometres from the Earth.

While neither Dimorphos, nor Didymos, the larger asteroid the former orbits, posed any threat to Earth, Tuesday's mission was the first demonstration of what future planetary defence technology might look like.

No rock too far

While crashing a spacecraft into an asteroid seems like a fairly simple task on paper, it requires tremendous technology-driven precision.

First, DART had to distinguish between the two asteroids, Dimorphos and Didymos, around an hour before the collision, a feat it achieved with the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO).

Coupled with sophisticated guidance systems and Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation (SMART Nav) algorithms, the 570 kilogram DART spacecraft hurtled through space and crashed into Dimorphos at a speed of a whopping 14,000 miles per hour.

With the crash, NASA demonstrated that it can accurately target small asteroids millions of kilometres away from the Earth, a capability that is critical to the success of future planetary defence missions.

"Now we know we can aim a spacecraft with the precision needed to impact even a small body in space. Just a small change in its speed is all we need to make a significant difference in the path an asteroid travels," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

What happens now?

While the successful impact of the DART spacecraft with Dimorphos marked the end of a long project for engineers, asteroid scientists will now have to examine data and the images captured to determine the effectiveness of the collision.

A little over two weeks before the DART spacecraft crashed into Dimorphos, its CubeSat companion, the Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube), deployed from it to capture images of the impact and the cloud of ejected matter from the collision.

Further, at the time of impact, the James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble, and around 40 Earth-based telescopes were pointed towards Dimorphos to capture the collision.

The data collected from the same will now be analysed over the coming days and weeks to determine whether DART managed to deflect Dimorphos to the extent that was expected.

Dimorphos orbits Didymos every 11 hours and 55 minutes and scientists will measure how much Dimorphos has sped up after the collision. The collision is expected to have moved Dimorphos closer to Didymos, and the change in orbital time is expected to be seven minutes.

Why is it important?

While there is no threat to the Earth from rogue asteroids at the moment (NASA doesn’t foresee any asteroid collisions for the next 100 years), DART provides a platform for the development of future asteroid deflection technology against unwelcome celestial visitors.

“DART’s success provides a significant addition to the essential toolbox we must have to protect Earth from a devastating impact by an asteroid. This demonstrates we are no longer powerless to prevent this type of natural disaster. Coupled with enhanced capabilities to accelerate finding the remaining hazardous asteroid population by our next Planetary Defense mission, the Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor, a DART successor could provide what we need to save the day,” said Lindley Johnson, NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer.

(With agency inputs)