Scientists have successfully revived microbes that had lain dormant at the bottom of the sea since the age of the dinosaurs, allowing the organisms to eat and even multiply after eons in the deep.

Their research sheds light on the remarkable survival power of some of Earth's most primitive species, which can exist for tens of millions of years with barely any oxygen or food before springing back to life in the lab.

A team led by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology analysed ancient sediment samples deposited more than 100 million years ago on the seabed of the South Pacific.

The region is renowned for having far fewer nutrients in its sediment than normal, making it a far-from-ideal site to maintain life over millennia.

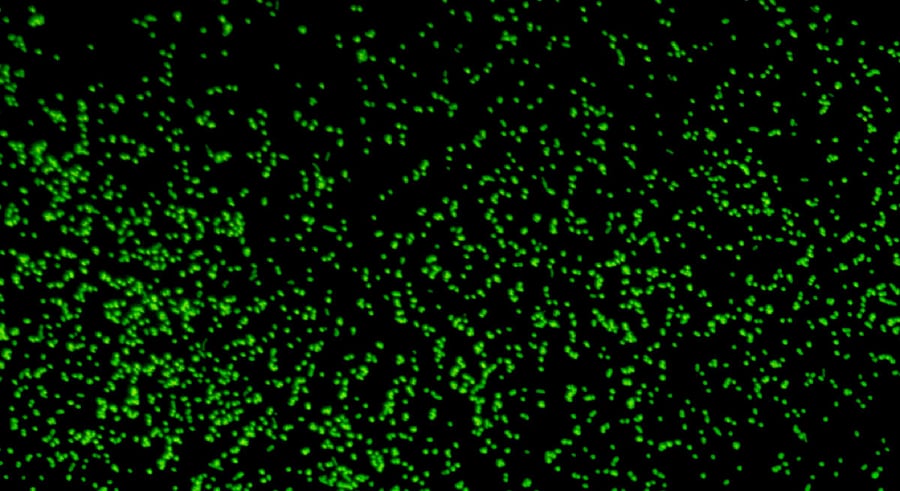

The team incubated the samples to help coax the microbes out of their epoch-spanning slumber.

Astonishingly, they were able to revive nearly all of the microorganisms.

"When I found them, I was first sceptical whether the findings are from some mistake or a failure in the experiment," said lead author Yuki Morono.

"We now know that there is no age limit for (organisms in the) sub-seafloor biosphere," he told AFP.

URI Graduate School of Oceanography professor and study co-author Steven D'Hondt said the microbes came from the oldest sediment drilled from the seabed.

"In the oldest sediment we've drilled, with the least amount of food, there are still living organisms, and they can wake up, grow and multiply," he said.

Morono explained that oxygen traces in the sediment allowed the microbes to stay alive for millions of years while expending virtually no energy.

Energy levels for seabed microbes "are million of times lower than that of surface microbes," he said.

Such levels would be far too low to sustain the surface microbes, and Morono said it was a mystery how the seabed organisms had managed to survive.

Previous studies have shown how bacteria can live on some of the least hospitable places on Earth, including around undersea vents that are devoid of oxygen.

Morono said the new research, published in the journal Nature Communications, proved the remarkable staying power of some of Earth's simplest living structures.

"Unlike us, microbes grow their population by divisions, so they do not actually have the concept of lifespan," he added.