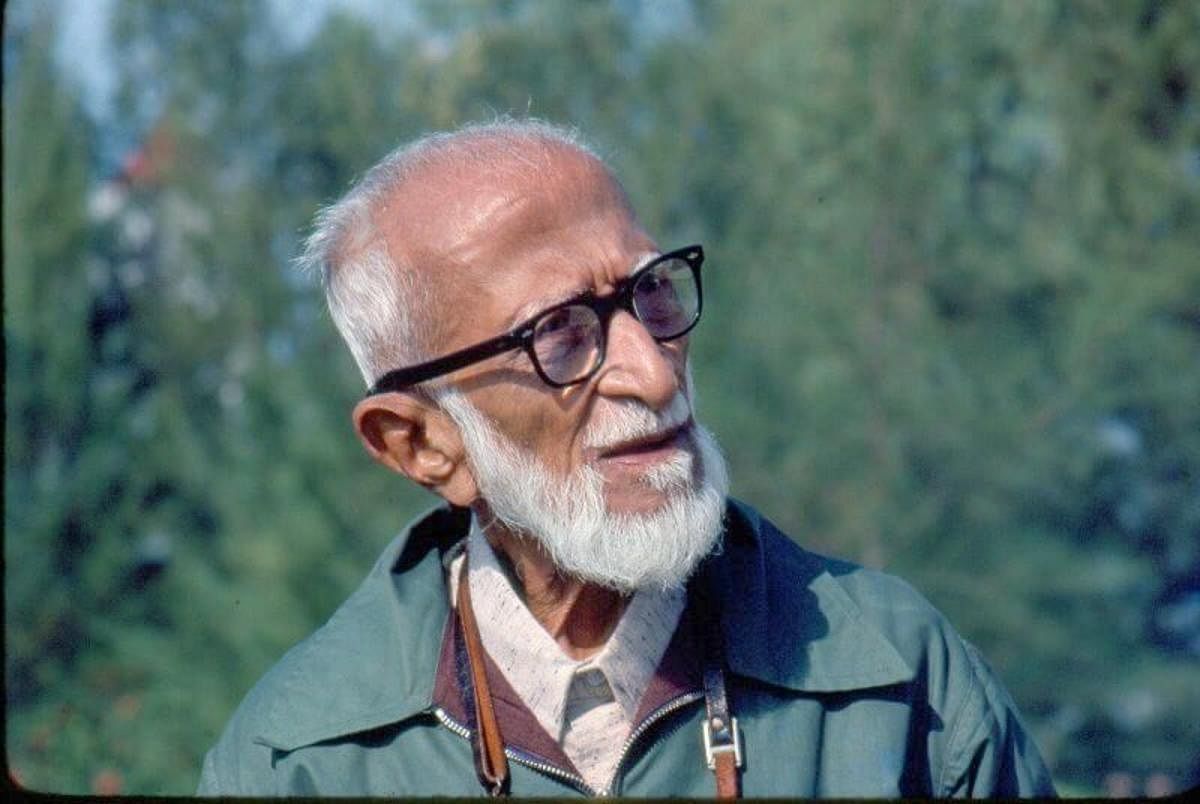

Where would Indian ornithology be without the famous birdman of India, Dr Salim Ali? Not very far; we would still be scrambling to put all the pieces together about the diverse and natural avifauna of this country, said the bird experts who knew him.

Born on November 12, 1896, at the tail end of the 19th Century when India was still a jewel in the British crown, Ali belonged to a well-to-do family that charted a path for him to a college education at St Xavier’s in Mumbai and after that, a respectable profession of some sort. In retrospect, his family should have known better.

As Bittu Sahgal, president of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), told DH: “Ali was anything but a conformist. He was not a backer of the status quo and being a natural outdoorsman, he was far from the classroom as he could possibly be in his mind.”

As an avid hunter, young Ali was known to walk through the woods around his family home with a Daisy airgun, shooting birds. But then sometime between 1915 and 1918, he shot a sparrow which was found to have a uncharacteristic yellow-coloured throat patch.

“When he took the bird to the BNHS for inspection, the society’s Honorary Secretary W S Millard had a shock. The bird, a yellow-throated sparrow, the Petronia xanthocollis, was a rare species of bird that had not been common,” Sahgal explained.

Certain that he had stumbled upon something rare, if not precious, appeared to trigger something in the young Ali. Sahgal believes it was a formative moment for the young man. “Millard took him under his wing (in a manner of speaking) and Ali decided he would study birds to understand why species were so different,” he added.

However, his sidetrack into the Society forced him to quit college. His exasperated family sent him packing to Tavoy in Burma (now Myanmar), in 1919, to manage the family’s wolfram (tungsten) mining and timber business. The assignment proved godsend because Ali was able to wander in the thick forests around the mining concern, becoming acquainted with the birds in that part of Burma and with forest department officials, J C Hopwood and Berthold Ribbentrop who helped him refine his birding skills.

Soon, the mining company had also gone bust and Ali returned to Mumbai, where by 1928, he could be found at the-then newly opened Prince of Wales Museum, working as a guide lecturer. In the intervening years between being a failed mining executive and a lecturer, Ali had returned to St Xavier’s where he had obtained a BSc in Zoology.

By 1947, he had become an influential figure behind the BNHS and was canvassing the government to help set up several wildlife reserves, chief of all the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary (Keoladeo National Park).

Dr S Subramanya, a former faculty at the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru who worked with him at Point Calimere, Bharatpur and at Harike during 1980-81 described slim, diminutive Ali as a force of nature, whose energy appeared boundless.

“He would continue to trudge through forest tracks when most younger companies were ready to stop. He never really had any formal degree in ornithology, but the remarkable thing about him was his passion for Indian birds, which allowed him to write 'The Book of Indian Birds' in 1941, through which he bought birdwatching, which was usually a pass-time of the elite till then, to the common man of India.

But it was a series of bird surveys in various Princely States of Hyderabad, Travancore and Cochin, Bhopal, Bastar, Bahawalpur, Mysore, Gujarat, Kutch, Gwalior and Indore between 1930-1956 and a number of exploratory trips across India, that really enabled him to gain first-hand knowledge on distribution, habits and ecology of Indian birds.

During 1939-40, he undertook a survey of the 'Birds of Mysore' with the permission of the Mysore Durbar and it spanned across nine districts of the state. One of the significant outcomes of this survey was the declaration of the islets in the midstream of Cauvery River near Srirangapatna, as the Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary, which he chanced upon during the survey. No sooner he finished his survey in 1940, he wrote to the Mysore Government highlighting the need for conservation of the spectacular congregation of birds, and an order was issued overnight.

An honorary doctorate followed in 1958 which finally gave him the title of “Dr,” which obviated his lack of a formal PhD. “It was a validation of his expertise,” Sahgal explained.

Then, in 1964, came the first volume of what would be his 10-volume magnum opus, “The Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan,” co-authored with the American conservationist, Sidney Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution. Dr Subramanya describes the volumes as the third such attempt at an avifaunal masterwork.

The first attempted by the 19th century Indian Civil Servant, A O Hume, whose work was quashed after his copious notes on birds were stolen by a servant and sold as scrap paper. The second attempt was by Hugh Whistler, a policeman and birdwatcher who collaborated with British ornithologist Claud Buchanan Ticehurst and together worked on the ultimate handbook on Indian birds. Both men died before it could be completed in the 1940s. However, this work would later become the base for Ali and Ripley’s “Handbook of the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent.”

“It is a monumental work that is still regarded as the final word on the matter of Indian birds,” Sahgal said.

Where would we be without this seminal work? “Not to the extent where we are now. His work filled a huge gap in our understanding of Indian birds and their range of diversity, habits and distribution in India,” Dr Subramanya added.

But his contributions were more deep-seated than that to Sahgal. “He was really the first to understand and make clear what we were doing to the biodiversity of the Indian subcontinent, which was once the richest on the planet. He really understood that India after independence undertook a decision to destroy our natural riches to create jobs and sustain the economy,” Sahgal said.

“Once we understood its impact, we realised what needed to be restored. This is what is driving conservation efforts in the country. That was Dr Ali’s ultimate legacy,” he added.