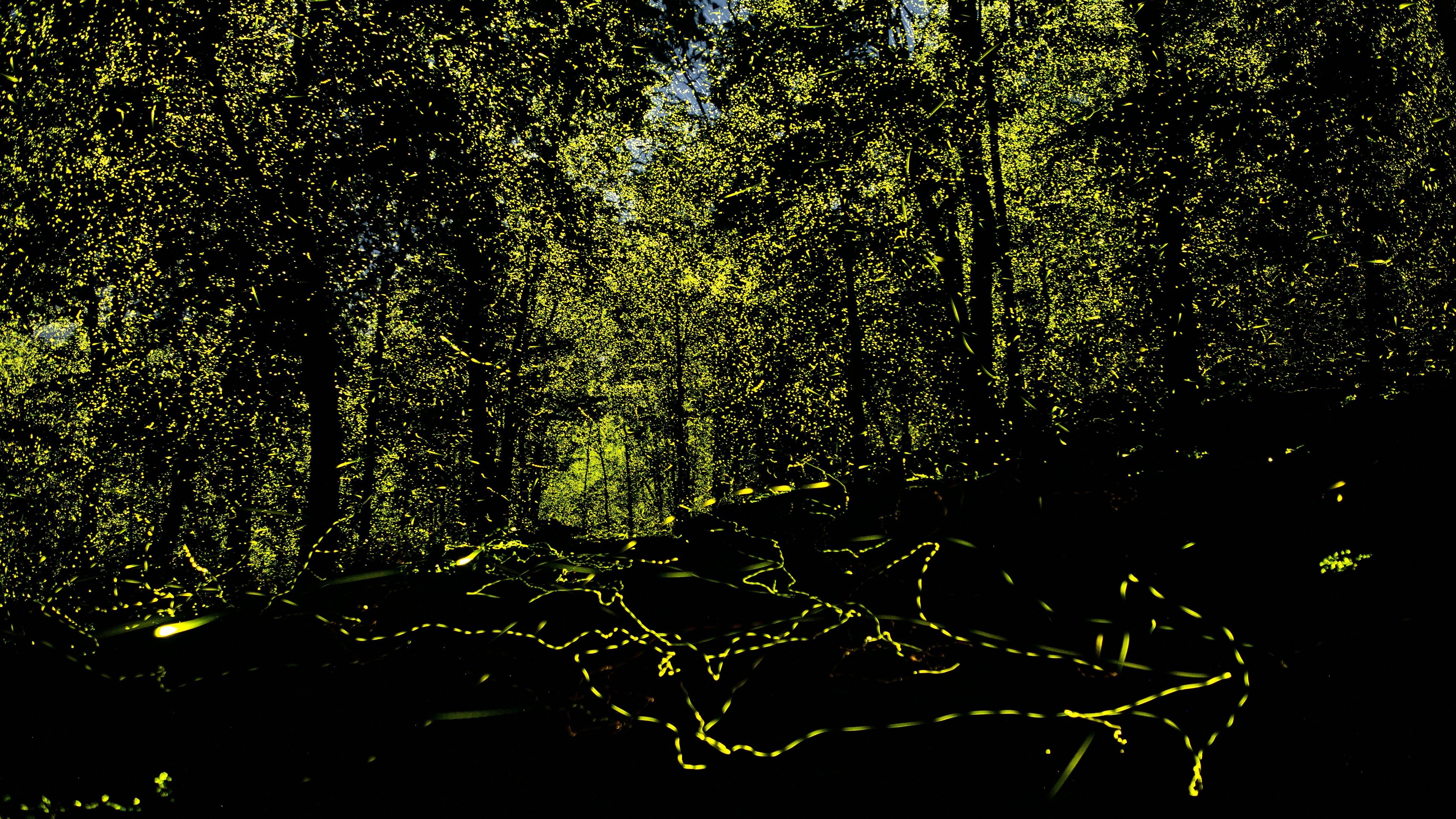

Male fireflies belonging to the Abscondita terminalis species coming down to mate.

PHOTO CREDIT: SRIRAM MURALI

Luminous trails shimmering in the gentle breeze cast a spell of wonder and magic in Anamalai Tiger Reserve(ATR) — a biodiversity hotspot in the Western Ghats known for being home to some of the largest populations of fireflies in the world. Several species of fireflies paint the dark, dense forests with their unique colours, flash patterns and mating rituals.

Flashes of large congregations of fireflies fill the forests during specific times of the year. The timing and quality of the South West and North East monsoons determine when the fireflies come out to flash. Fireflies are seasonal and time every stage of their life with available moisture.

Like most insects, fireflies go through a complete metamorphosis containing four stages in their life cycle. Born as tiny larvae, they feed on soft-bodied insects for up to a year, growing as long as 5 to 6 cm.

Typically, firefly larvae feed on earthworms, slugs and snails. In ATR, they feed on leeches. Studies by Wild and Dark Earth, a nongovernment organisation conserving nocturnal habitats, show that the larvae consume 5 to 10 leeches every night. These voracious predators hardly have any predators. They are toxic and distasteful.

Like the colourful poisonous frogs in the Amazon rainforests, the larvae ensure their identity is known through bioluminescence. They glow in a distinct, bright lime-green colour, warning predators. The larvae need moisture to prevent them from desiccating. During the peak summer, they move towards any residual moisture underground. In ATR, the wet, evergreen forests provide the perfect habitat for firefly larvae.

At the peak of summer, when the forest is parched, the firefly larvae await the seasonal rains to surface up to the ground. After a couple of heavy showers, the larvae become active again and prepare to go into pupation. The pupae also need a moist environment to stay put for almost two weeks. They choose shaded spots under dead logs and leaf litter

Blinking in sync

Fireflies can prolong any stage of their life cycle and wait for seasonal rains to move on. Once they pupate, they become the adult fireflies with wings that we are familiar with. These winged beetles flash and mate for the next two weeks, involving intricate flash patterns and mating rituals.

The most common species found here are the synchronous fireflies that flash in unison in one of nature’s greatest light symphonies. Male fireflies perched on trees coordinate their flashes to attract females from a distance. Several sparkles (groups of fireflies) flash in rhythmic and cyclical patterns in a yellowish-green colour.

Darkness is a cue for fireflies to flash. Fireflies in the trenches glow first, followed by the ones up in the canopy. After several hours of synchronous flashing, they come down looking for mates. Male fireflies fly low to the ground, each with its unique flash pattern, to woo females. When a female likes an individual, it signals by mimicking the male’s flash pattern.

The pair continue to glow as they mate. These are fireflies of the genus Abscondita. During the day, they prefer to rest on trees with large leaves, protecting them from sunlight. At night, they choose interspersed trees so that their flashes can be seen from a distance. They display themselves in large numbers within the reserve, even on the teak and rosewood plantations.

New colours and designs

The winter months after the northeast monsoon rains bring out other fireflies with unique flash patterns and colours. Some flash in quick bursts, while others glow constantly in all shades of yellow and green.

Grasslands and riverine habitats host fireflies that flash in quick and increasing bursts of flashes as they fly, looking for mates. Dense, wooded, hilly evergreen forests host a very unique species of firefly.

Belonging to the genus Lamprigera, these recently discovered fireflies hover in the air and fly swiftly while glowing constantly in lime green and blue. Within thirty minutes of sunset, male fireflies fly low to the ground, looking to attract flightless females under dense foliage. Females stay in the larval form throughout their lives. Their flashes appear blue from a distance due to the Purkinje effect—eyes being more sensitive to blue light at night.

Six species documented

Wild and Dark Earth members have studied firefly behaviour, ecology and diversity in ATR since 2022. The team has documented six species of fireflies, two of which could be new. Scientists at the Advanced Institute for Wildlife Conservation and the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) have been helping the team to identify the species.

We are also keen on monitoring firefly populations and understanding the factors that affect them. The timing and quality of the monsoon rains play a critical role in a successful firefly season. The lack of enough rain caused a decline in populations in one forest area in 2023. Climate change poses a significant threat to their survival. A few seasons with little rains could wipe them off the reserve.

Though artificial lights do not pose an imminent threat because there’s hardly any development within the reserve, the light spills from nearby towns must be monitored. With firefly populations declining across the world, it is critical to conserve these precious habitats.

(The author is a co-founder of Wild and Dark Earth and an IUCN Species Survival Commission Firefly Specialist Group member)