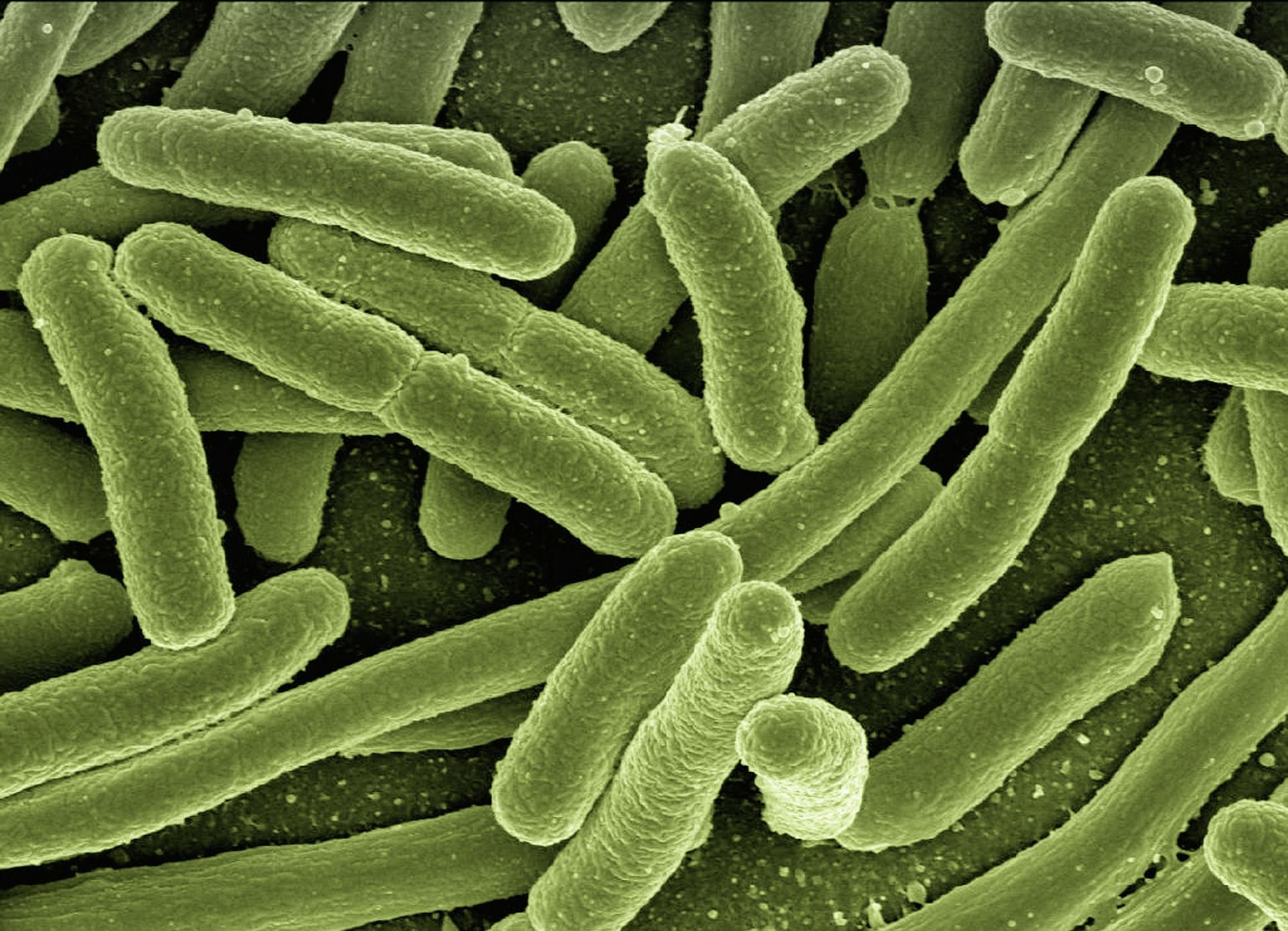

Scientists at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have discovered two species of bacteria that feed on metal, manganese to be specific, by accident.

For almost a century, scientists have been predicting the existence of such microbes, but they have been discovered only now.

If Marvel’s Magneto can manipulate metal at will, these microscopic organisms possess the power to eat them all up, for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Jared Leadbetter, a microbiologist, in collaboration with postdoctoral scholar Hang Yu, dubbed the two species of bacteria as ‘Candidatus Manganitrophus noduliformans’ and ‘Ramlibacter lithotrophicus’, according to the science magazine Nature.

"These are the first bacteria found to use manganese as their source of fuel," says Leadbetter in his findings. They can metabolise seemingly unlikely materials like manganese and release energy that is useful to their cell.

Scientists were aware earlier that this bacteria would be able to degrade pollutants in groundwater through a process called bioremediation. During this process, several key organisms will “reduce” manganese oxide (donate electrons, similar to how humans use oxygen). For the first time, scientists have an inkling where the manganese oxide comes from.

Leadbetter had left a glass jar soiled with a light, chalk-like form of manganese to soak in tap water in his Caltech office sink for an unrelated experiment. Returning to his office after months, he found the jar coated with a dark substance, according to the Science Daily article.

"I thought, 'What is that?'" he told the magazine, "I started to wonder if long-sought-after microbes might be responsible, so we systematically performed tests to figure that out.”

The black coating turned out to be oxidised manganese produced by the metal-eating bacteria that had most probably come from the tap water, the report said.

"There is evidence that relatives of these creatures reside in groundwater, and a portion of Pasadena's drinking water is pumped from local aquifers," he said.

This finding can shed light on why drinking-water-distribution systems are frequently clogged by manganese oxides, in a dark and slum-like form.

"There is a whole set of environmental engineering literature on drinking-water-distribution systems getting clogged by manganese oxides," said Leadbetter, to Science Daily.

"But how and for what reason such material is generated there has remained an enigma. Clearly, many scientists have considered that bacteria using manganese for energy might be responsible, but evidence supporting this idea was not available until now," he said.

"The bacteria we have discovered can produce it, thus they enjoy a lifestyle that also serves to supply the other microbes with what they need to perform reactions that we consider to be beneficial and desirable," says Leadbetter.

The research, funded by Caltech and NASA, can solve the mystery of manganese modules that dot the seafloor. As large as a grapefruit, these nodules were first spotted by mariners of the HMS Challenger in 1870s. In more recent times, mining companies have made plans to harvest and exploit these nodules as rare metals are found within.

Leadbetter and Yu now think that similar microbes might be responsible for the formation of these nodules at the bottom of the sea, according to the article. They plan to investigate the matter further as little is understood about how these nodules are formed in the first place. "This underscores the need to better understand marine manganese nodules before they are decimated by mining," said Yu.

Geobiology, a professor Woodward Fischer at Caltech who was not involved in the experiment, also noted, “This discovery from Jared and Hang fills a major intellectual gap in our understanding of Earth's elemental cycles, and adds to the diverse ways in which manganese, an abstruse but common transition metal, has shaped the evolution of life on our planet.”