Seven months in space, a mission that was decades in the making and cost billions of dollars, all to answer the question: was there ever life on Mars?

NASA's Perseverance rover prepares for touchdown on the Red Planet Thursday to search for telltale signs of microbes that might have existed there billions of years ago, when conditions were warmer and wetter than they are today.

Over the course of several years, it will attempt to collect 30 rock and soil samples in sealed tubes, to be eventually sent back to Earth sometime in the 2030s for lab analysis.

"It's of course trying to make significant progress in answering one of the questions that has been with us for many centuries, namely: are we alone in the universe?" NASA Associate Administrator Thomas Zurbuchen said Wednesday.

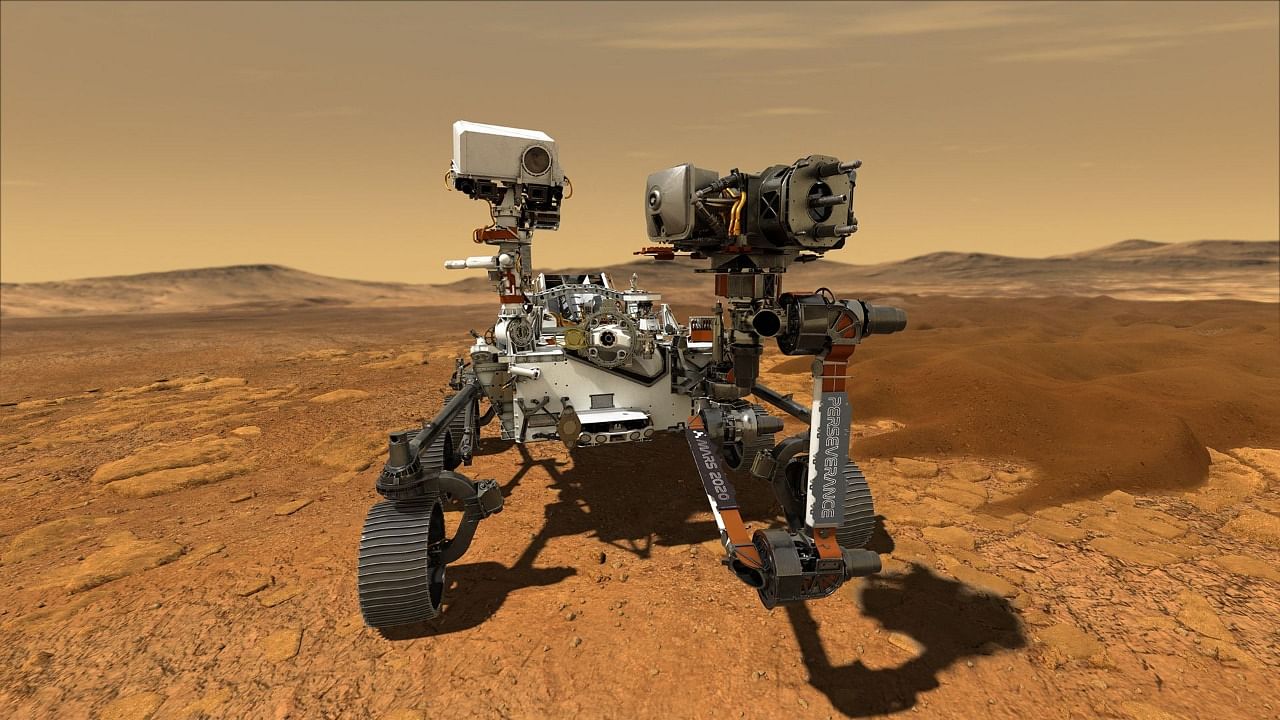

Perseverance is the largest and most sophisticated vehicle ever sent to Mars.

About the size of an SUV, it weighs a ton, is equipped with a seven-foot (two-metre) long robotic arm, has 19 cameras, two microphones, and a suite of cutting-edge instruments to assist in its scientific goals.

Before it can embark on its lofty quest, it will first need to survive the dreaded "seven minutes of terror" -- the risky landing procedure that has scuppered nearly 50 per cent of all missions to the planet.

Shortly after 3:30 pm Eastern Time (0230 IST), the spacecraft will careen into the Martian atmosphere at 12,500 miles per hour (20,000 kilometres per hour), protected by its heat shield.

It will then deploy a supersonic parachute the size of a Little League field, before firing up an eight-engined jetpack to slow its descent even further, and then eventually lower the rover carefully to the ground on a set of cables.

Its target site, the Jezero Crater, is full of perilous terrain, but thanks to new instruments Perseverance is capable of landing with far greater precision than any robot sent before it.

Scientists believe that around 3.5 billion years ago the crater was home to a river that flowed into a lake, depositing sediment in a fan-shaped delta.

"We have very strong evidence that Mars could have supported life in its distant past," Ken Williford, the mission's deputy project scientist said Wednesday.

But if past exploration has determined the planet was once habitable, Perseverance is tasked with determining whether it was actually inhabited.

It will begin drilling its first samples in summer, and its engineers have planned for it to traverse first the delta, then the ancient lake shore, and finally the edges of the crater.

Perseverance's top speed of 0.1 miles per hour is sluggish by Earth standards but faster than any of its predecessors, and along the way it will deploy new instruments to scan for organic matter, map chemical composition, and zap rocks with a laser to study the vapour.

"We astrobiologists have been dreaming about this mission for decades," said Mary Voytek, head of NASA's astrobiology program.

Despite its state-of-the-art technology, bringing samples back to Earth remains crucial because of anticipated ambiguities in the specimens it documents.

For example, fossils that arose from ancient microbes may look suspiciously similar to patterns caused by precipitation.

Before getting to the main mission, NASA wants to run several eye-catching experiments.

Tucked under Perseverance's belly is a small helicopter drone that will attempt the first powered flight on another planet.

The helicopter, dubbed Ingenuity, will have to achieve lift in an atmosphere that's one per cent the density of Earth's, in a demonstration of concept that could revolutionize the way we explore other planets

Another experiment involves an instrument that can convert oxygen from Mars' primarily carbon dioxide atmosphere, much like a plant, using the process of electrolysis to produce 10 grams of oxygen an hour.

The idea is that humans eventually won't need to carry their own oxygen, which is crucial for rocket fuel as well as for breathing.

Perseverance's two microphones will meanwhile attempt to record the Martian soundscape for the very first time, after past efforts failed.

The rover is only the fifth ever to set its wheels down on Mars. The feat was first accomplished in 1997 and all of them have been American.

That will probably soon change: China's Tianwen-1 spacecraft entered Martian orbit last week and is expected to touch down with a stationary lander and a rover in May.