One of the great shaggy-dog mysteries of the sky continues to mesmerize astronomers. That would be the nature of a strange interloper, Oumuamua, that came zooming through the solar system in 2017. Interstellar comet? Cosmic iceberg? Alien space wreck?

Last week two astronomers from Arizona State University, Alan Jackson and Steven Desch, offered the most solid explanation yet: Oumuamua was a chip off a faraway planet belonging to another star. Long ago, a collision with an asteroid broke it off and sent it careering through space.

“This research is exciting in that we’ve probably resolved the mystery of what Oumuamua is, and we can reasonably identify it as a chunk of an ‘exo-Pluto,’ a Pluto-like planet in another solar system,” Desch said in a statement released by the American Geophysical Union. “Until now, we’ve had no way to know if other solar systems have Pluto-like planets, but now we have seen a chunk of one pass by Earth.”

They announced their results at a meeting of the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference on March 17 and in a pair of papers in The Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The operative words are “probably resolved.” Although astronomers agree that the new model could answer some questions about the mystery flyby, many more remain in motion.

“What makes Oumuamua both interesting and frustrating is that none of the theories are a slam-dunk,” said Gregory Laughlin, an astronomer at Yale who has studied Oumuamua.

Astronomers in Hawaii, patrolling for killer asteroids and other flashes in the night with the Pan-STARRS1 telescope on Maui, first spotted this mystery object speeding away from the sun at 50 miles per second on October 19, 2017. They called it Oumuamua — Hawaiian for “scout” or “messenger.” But what was the message?

The trajectory of the object indicated that it had come from outside the solar system and that after a brief buzz past the inner worlds of our system it was bound for deep space. By the time it was noticed, it had already passed Earth. Astronomers concluded from the variations in its brightness that it was a tumbling object, longer than it was wide.

Astronomers had long thought than an orphan comet might be the first interstellar visitor to our region because comets, residing in distant clouds, are easily detached from their home stars. Oumuamua did not have a tail, however, or the gaseous cloud that forms around a comet nucleus, so it was tentatively identified as a wandering asteroid.

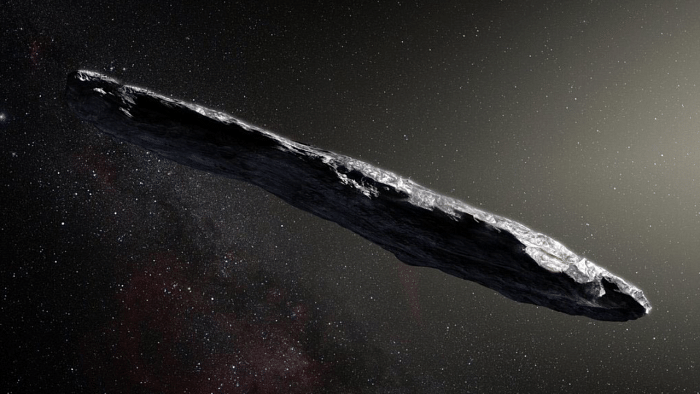

An artist’s conception of a reddish, cigar-shaped rock gained widespread circulation. Some astronomers have suggested that it could be shaped like a pancake.

But when Oumuamua was on the way out of the solar system, it sped up. Comets often act this way, as they are given a kick from jets of evaporating gas on their surfaces. So perhaps it was a comet after all — but a weird one. An illustration accompanying Jackson and Desch’s result shows it looking like a cracker or a flying cow chip.

The mystery deepened in 2018 with the discovery of 2I/Borisov, another interstellar interloper that behaved more like an ordinary comet.

Theories and models abounded in the literature. Avi Loeb, an astronomer at Harvard, rode onto the bestseller list earlier this year with a book, “Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth,” arguing that Oumuamua was an alien space vessel of some kind, and scolding the astronomical community for not thinking more outside the box about extraterrestrial life. The object’s imputed shape, he said, could be perfectly consistent with that of a light sail of the type that Loeb and his colleagues, in an ambitious project called Breakthrough Starshot, hope to send to Alpha Centauri sometime this century.

But an international team of comet experts writing in Nature Astronomy in 2019 under the name of the Oumuamua ISSI Team concluded that all the data were consistent with “a purely natural origin” for Oumuamua.

Last year Laughlin of Yale and his student Darryl Seligman, now at the University of Chicago, suggested that Oumuamua was a primordial iceberg of hydrogen that had formed in the dark, cold centre of a molecular cloud, one of the vast assemblages of primordial gas that give rise to stars.

The problem was that it was hard to explain how the hydrogen, which freezes at a temperature around 3 degrees Kelvin, barely above absolute zero, would stay frozen on the long trip from its birth to here.

Inspired by the hydrogen ice idea, Jackson and Desch investigated other kinds of icebergs that might fill the bill. They finally hit on nitrogen.

“We’ve never seen any examples of hydrogen ice in nature,” Desch said in an email. But when the New Horizons spacecraft went past the previously unexplored Pluto in 2015, it found a world awash in nitrogen glaciers.

“Oumuamua was small, about half as long as a city block and only as thick as a three-story building, but it was very shiny,” they wrote in one of their papers. “The shininess is about the same as the surfaces of Pluto and Triton, which are also covered in nitrogen ice.” Triton is a moon of Neptune.

In the scenario favoured by Desch and Jackson, the nascent Oumuamua was knocked from a Pluto-like object that was circling a distant star some half-billion years ago. It would have originally been roundish, but as it travelled through space it was carved away by cosmic rays.

By the time it entered our solar system in 1995 or so, it had lost half its original mass, according to their model. During its passage around the sun it likely melted to a sliver, like a bar of soap in the shower, the researchers say. Only 10% would have remained by the time it left the solar system, boosted by the rocket-like effect of evaporating nitrogen.

Nitrogen sublimates at about 25 degrees Kelvin, Desch said: “We calculate that Oumuamua reached temperatures in the 45 to 50 K range while it rounded the sun, so it was sublimating nitrogen gas like crazy, hence the strong mass loss.”

Desch and Jackson concluded: “A key advantage of the proposal we advance here of a nitrogen ice fragment is that it can simultaneously explain all of the important observational characteristics of Oumuamua, and that material of this composition is found in the solar system. We, therefore, conclude that Oumuamua is an example of an uncommon but certainly not exotic object: a fragment of a differentiated Pluto-like planet from another stellar system.”

Of course, that’s not the end of the story.

In an email, Loeb complained, among other things, that if Oumuamua was made of nitrogen it should also contain carbon (which was not detected by the Spitzer Space Telescope), because both nitrogen and carbon are produced by a thermonuclear carbon-nitrogen-oxygen cycle in stars.

Desch responded in an email: “Spoken like a cosmologist!” He went on to note that planets have ways of sifting and separating the elements they were born with. Otherwise, Earth’s atmosphere, which is 79% nitrogen, should be several per cent carbon instead of one-tenth of 1% carbon. Or, as another astronomer pointed out, the Great Lakes would all be full of sparkling water.

Desch noted, moreover, that the reddish colour of Oumuamua is an exact match to the redness of the ice on Pluto, which is 0.1% carbon, in the form of methane.

Another issue is statistics. How is it that these cosmic icebergs are so common — more than 50 trillion per cubic light-year of space, according to a calculation by Laughlin — that the Pan-STARRS project would have discovered one after just five years of searching?

“That puts a lot of pressure on the galaxy to manufacture exo-Plutos,” Laughlin said.

If so, Oumuamua was just the tip of an unsuspected iceberg, so to speak, which is exactly what Desch and Jackson contend.

A lot of things get ejected from planetary systems, Desch pointed out; older papers assumed that these would be as big as comets, and so predicted them in much lower numbers. But if they are smaller, Desch added, there would be many more fragments flying out, so something like Oumuamua would not necessarily be an anomaly.

“So far we’ve seen one N2 ice fragment and one comet among the interstellar objects,” he wrote in an email. “Small-number statistics doesn’t get much smaller than that.” Those numbers were about what is expected, according to their calculations, he said: “Maybe we got a little lucky to see one so quickly, but it’s not a fluke or anything. This is a common object to be entering our solar system.”

If more are out there to be seen, they should soon be detectable by the Vera Rubin Observatory, a giant telescope in Chile that will start stalking the sky later this decade.

Other astronomers have suggested a different creation mechanics, in which a distant planet passing close to its star is torn apart by tidal forces. This would result in fragments even more oblong, closer in resemblance to a cigar than a cookie, casting doubt on the nitrogen ice theory, Laughlin said. That is a controversy that could be resolved by better images, if and when the next interstellar interloper comes by.

But as Laughlin said, nature might have the last laugh. “Given the rule of thumb that 99% of one’s own cool ideas tend not to work out,” he said, “I think the smart money is on another object with Oumuamua’s characteristic weirdnesses never again being observed.”