A quick search on the Internet will tell you that weaving kamblis or woollen blankets was once a steady source of income for the pastoral Kuruba community, which inhabits Northern Karnataka. When Bengaluru-based textile revivalist and entrepreneur Pavithra Muddaya learnt that the craft was facing extinction, she felt compelled to do something about it. She embarked on a design intervention, titled The Kambli Project, the results of which are currently on display at her store, Vimor, in Bengaluru.

Pavithra’s mission to bring the textile back from the brink of death, took her to the village of Karagaon in Belgaum, which is known for its handwoven kamblis. “What struck me most about this community was their sustainable way of life. On interacting with them, you realise it is central to their culture,” she says. The community rears sheep, uses their wool for blankets and grazes them on farmland as this enriches the soil.

Also Read | A cliff-temple at Mahakuta

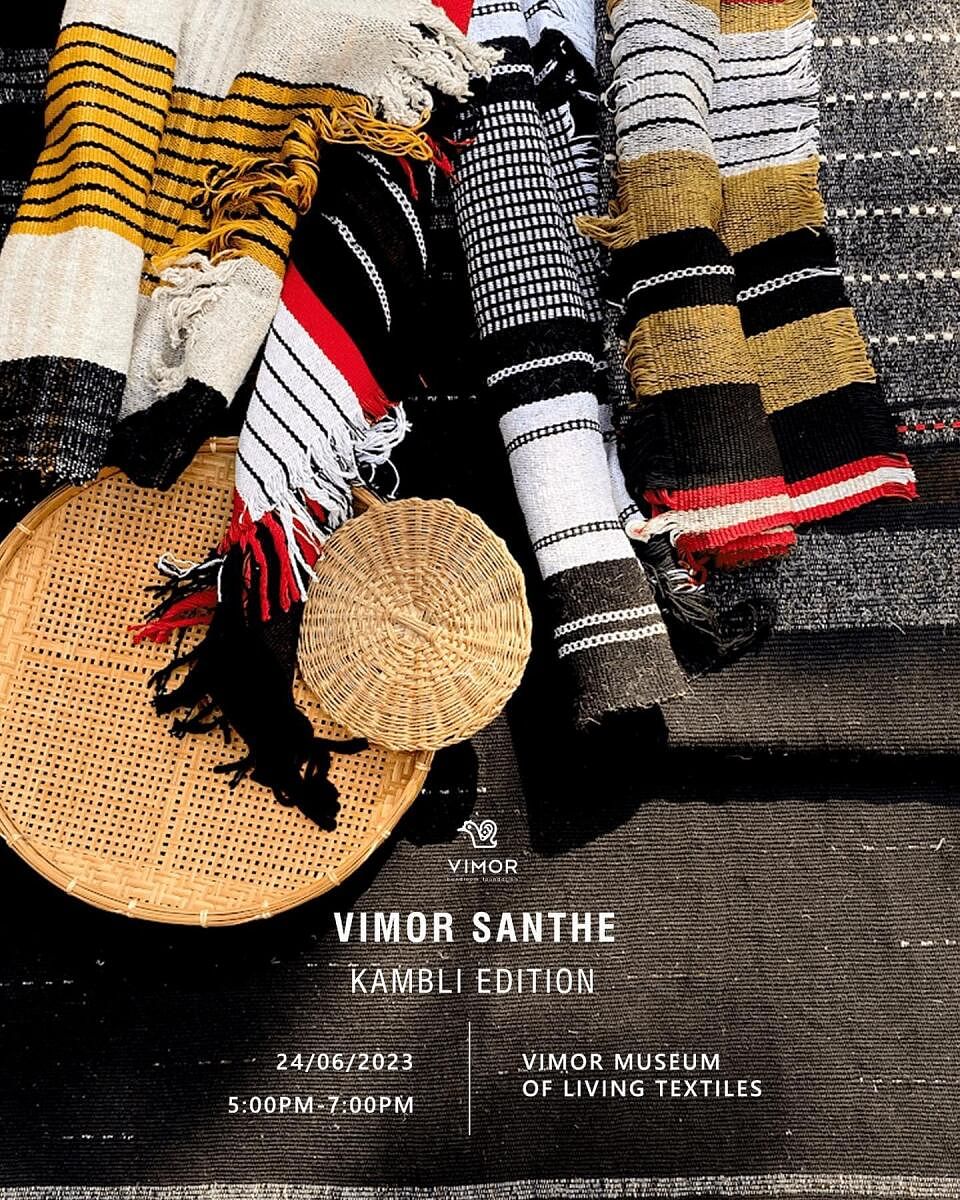

The colour black is a distinct feature of the blankets, which is due to the natural colour of the sheep’s coat. Often they blend it with cotton to soften the wool’s coarse texture. For the project, Pavithra mixed the wool with recycled silk and other waste fibres. The black wool is interspersed with stark white, vibrant red, bright yellow and muted brown yarn in each of the pieces. The fresh geometric patterns make the ages-old weave suitable for contemporary palates. “They were woven on a loom that looked prehistoric, 10 metres at a time,” says Pavithra, who started working with the weavers in 2020. When Covid-19 broke out, it stalled the whole process. Pavithra and her team, who work with weaving clusters across the country, supported the artisans with food, medicine and funds through the worst of the pandemic.

“The Kuruba weavers were among the most grateful for the help. And consequently were quite enthusiastic about giving us a chance with their traditional weave,” she shares, talking about the challenges of convincing the weavers to try new designs, colours and yarns.

“As it is their tradition, passed down through hundreds of years, it was important to be respectful and make them understand what will work for the modern consumer. At the same time, I didn’t want them to feel that their work was irrelevant,” she adds.

That she was instrumental in one of the weavers, Shankar Ningappa Sanakki, winning the national Marthand Singh award for his special weaving technique, called Nishani, was another factor that helped in her three-year journey.

Through The Kambli Project, the aim was to spotlight the weave to those outside the community, to showcase the various possibilities of how it can be used. To that end, the pieces the weavers have created as part of the project are not restricted to just blankets. The weave has been used to create rugs, wall hangings, basket bags, jackets and more.

“No special function or ceremony is complete without the presence of the kambli in some form or other. Even the black thread the children of the community wear around their wrist is made from the same wool,” she says, explaining the significance of the textile.