When the Centre accorded classical status to Tamil in 2004, some scholars argued it would open a Pandora’s box but those who resisted the Hindi imposition in south India felt the move might at least help the states reassert their regional identity and linguistic economy.

They hoped that such a move would help broaden the scope of federalism and create a democratic space incorporating equity as members of marginalised communities would get training and access to study and critique classical texts.

Two decades later, the number of ‘classical languages’ has grown to six but scholars and officials say not much has changed in the states' engagement with their historical roots, with the possible exception of Tamil Nadu, where an anti-Hindi wave dating back to 1930s created a sense of urgency to protect and promote Dravidian identity rooted in its classical texts.

The Centre for Excellence of Classical Tamil, which functioned from a corner of the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysuru for two years shifted to Chennai and transformed into the Central Institute of Classical Tamil (CICT). It also got a standalone building in 2022.

Though the institute appointed its full-time director only in 2020, it didn’t fall behind in research activities aimed at establishing the ancientness and uniqueness of Tamil.

In 16 years of its existence, the CICT published over 40 books on Tamil establishing its relevance. The institute has also released audio versions of Thirukkural, Pathu Paatu, and Tholkappiam, while pursuing several other areas of research. Also, it has eight publications in multimedia and non-book format under its name.

As a result, the funds flowed. Between 2014-15 and 2019-20, the CIST received an average of Rs 8.33 crore every year as against the annual average grant of Rs 1.02 crore given to Kannada and Telugu. The CIST received Rs 11.73 crore in 2020-21, not to mention the cost of a new building at Rs 24 crore.

High priority for Hindi

This stands in stark contrast to the zest with which the central governments have moved to impose Hindi, starting from language policy to the recent zeal, as announced in Lok Sabha, of promoting Hindi in foreign countries as a 'high priority'.

Data from 2017 to 2020 shows that the Department of Official Language alone has spent an average of Rs 65 crore every year to promote Hindi. This doesn't include the expenditure incurred by other government departments and institutions which pay for promoting Hindi from their pockets.

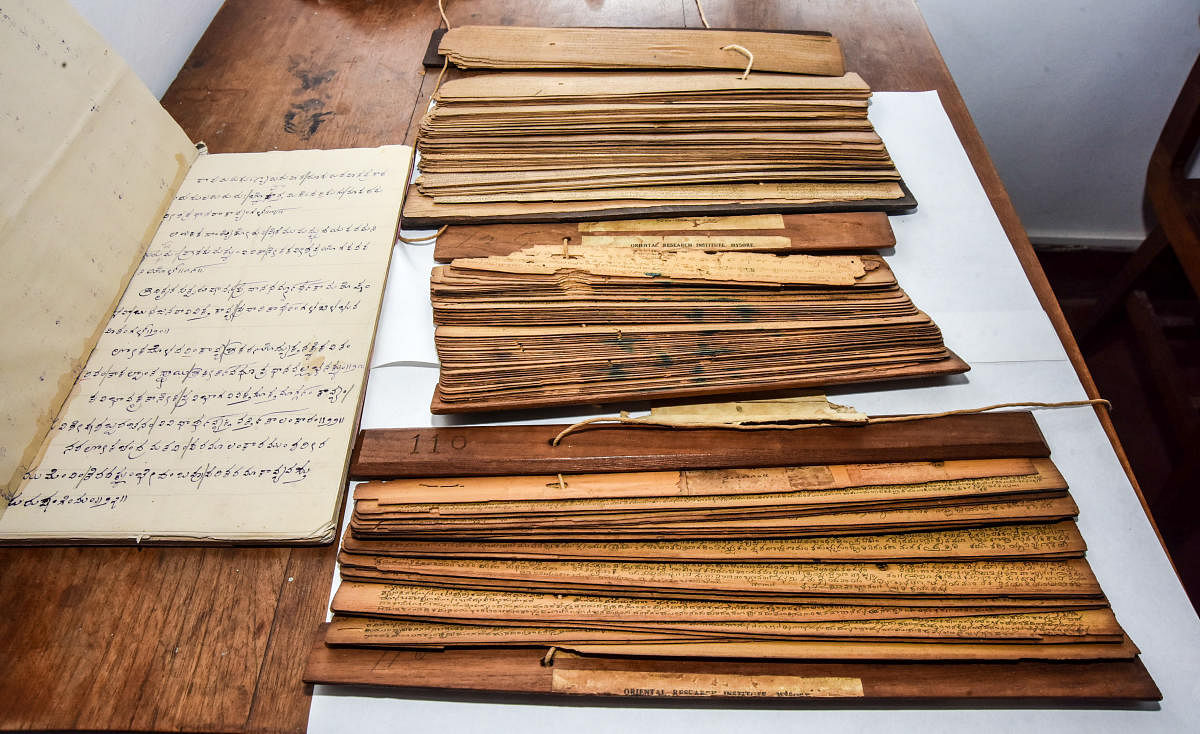

Kannada and Telugu both received classical status in 2008. The Centre of Excellence for Studies in Classical Kannada is yet to find its feet with the state and the central governments failing to provide a physical set-up and institutional autonomy in the past decade.

Telugu, which remained far behind Kannada, got a push after Vice President Venkaiah Naidu took up its case in 2019 and facilitated building infrastructure in Nellore. Plans are afoot to establish a campus in Tirupati.

In Kerala, however, the project remained a non-starter though Malayalam received the classical tag in 2013. The Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University was established by the Kerala government one year before but sources said not much has been done to initiate research in Malayalam.

A Centre of Excellence started with support from the Central Institute of Indian Languages under the Malayalam University. But the appointment of staff to the centre was delayed. “Any support to the research, like fellowships and awards, could be extended only through the centre of excellence. Once it (centre) becomes operational, we can initiate some steps,” said Anil Vallathol, Malayalam University vice-chancellor.

A senior official in the Department of Kannada and Culture said political will was necessary to “make the files move in Delhi”. He noted that the Centre of Excellence for Studies in Classical Kannada has received Rs 13.30 crore of which Rs 5.71 crore has been spent. “The Union government reduced funding in 2013-14 after the institute failed to utilise even half of the funds given in the previous year,” an official said.

“We have lost precious time in petty politics and downright ignorance. In 2017, the department’s commissioner took the initiative to hold a meeting with all the stakeholders. The Bangalore University came forward to accommodate a classical Kannada institute, which was planned at a cost of Rs 20 crore. However, in the absence of political backing, red-tapism shelved the project,” he added.

Writer Purushotham Bilimale, who recently retired as the professor of Kannada at the Kannada Language Chair, JNU, said the government should vigorously push for research besides working on institutional autonomy and infrastructure. “The problem is that unlike in Tamil Nadu, many politicians in Karnataka do not recognise the links between language, culture and identity. As a result, we do not see much work beyond sloganeering. At present, we don’t have much to show as achievement apart from the work done in CCIL,” he said.

Such ignorance is visible with the state wasting a few opportunities. The Delhi University’s two UGC-funded posts for Kannada language studies have been lost since 2011 because the state government didn’t appoint anyone. The Kannada language department at the Banaras Hindu University was lost when the state government failed to appoint a professor for the chair.

Muddling history, language

In recent decades, many researchers have warned about the death of classical languages with Sheldon Pollock, a scholar of Sanskrit, noting that India was “well on its way to losing its memory”, thanks to perverted language politics and an education system that fails to value scholars.

Noting that the lack of scholars who can read classical works means the loss of ability to critique the past and surrendering it to the abusers of memory, Pollock warned: “If classical scholars in India or elsewhere cede control of memory, it will be left to the delusions and ravings of the anti-historians.”

Such an attitude has also led to the closing of democratic space in literature and history as typified by the incident of Delhi University dropping A K Ramanujan’s essay ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation’.

Literary critic and cultural activist Ganesh N Devy said such incidents happen despite the fact that many books belonging to the classical period were produced by different social classes but Brahminical classes claimed them and 'purified' them.

“I have heard four versions of Ramayana, including the Gondi Ramayana. To claim only one version is correct is an effort to reject the diversity of Ramayana. It is time for us in this country to enable all classes of people to access ancient books. The classical language status can be an opportunity. People should be able to say they accept Gita but can’t accept the justification of the Varna system in Chapter 18. Besides, there are important texts, like the Mrcchakatika, which talk of social transformation and people’s power. Such books should be given new readings and interpretations to enrich culture and society. It will help protect the diversity of our culture,” he noted.

Anusha S Rao, a doctoral student in religion at the University of Toronto, said the study of classical languages and religion as an academic discipline was crucial to combat anti-historical claims. “We are still a long way from that in India. I don’t think anti-historicist claims are new or restricted to the ruling establishment. We need to remember that we are doing an injustice to the past by trying to fit our ideas and beliefs into ancient texts, and funding classical studies would be a great step,” she added.

Rajendra Prasad, a poet based in Mandya with an interest in classical Kannada literature, said those who commit to such studies should be chosen based on merit and compensated on par with those who get jobs through professional courses.

(With inputs from E T B Sivapriyan in Chennai and Arjun Raghunath in Thiruvananthapuram)

Check out latest DH videos here