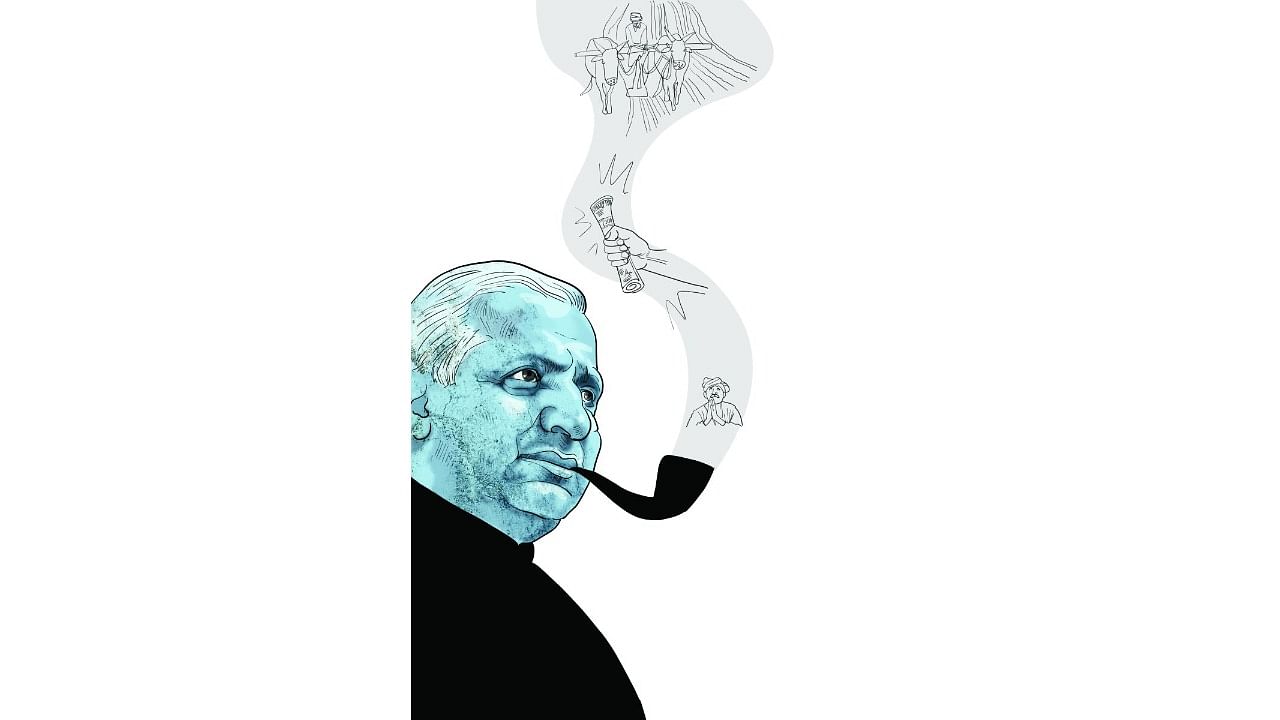

When Devaraj Urs stepped down as the CM in 1980 , P Lankesh, the renowned editor and filmmaker, wrote a piece about him. With IAS officers as intermediaries, the two had interacted, and Lankesh had said he might have profiled Urs much better had he spent five days independently with him.

I was haunted by what he had said about Urs’s rich, colourful personality. Over the years, I read and reread the piece. In 2015, newspaper reports said the Siddaramaiah government was preparing to celebrate Urs’s birth centenary. By then, I K Jahagirdar, Vaddarse Raghurama Shetty, and Ha.Ma. Nayak and others had written books about the Urs administration. As a reporter who had covered politics since 1990, I was intrigued by whatI had read and heard about Urs, and decided to meet people who had known him closely.

I made a list of about 40 people to talk to, covering such big names as H D Deve Gowda, A K Subbiah, S M Krishna, Dharam Singh, K H Srinivas, Mallikarjun Kharge, Kagodu Thimmappa, K R Ramesh Kumar, M Raghupathy. I started off by meeting them. I also met Urs’s childhood friends, relatives, journalists, and photographers.

B Subbayya Shetty, hailing from Surathkal, Mangaluru, was the land reforms minister in the Urs regime. He spoke about Urs in great detail. He gave me more names. Eventually, I met 61 people, and chronicled what they had to say. The chapters are in their voices, with little intervention from me.

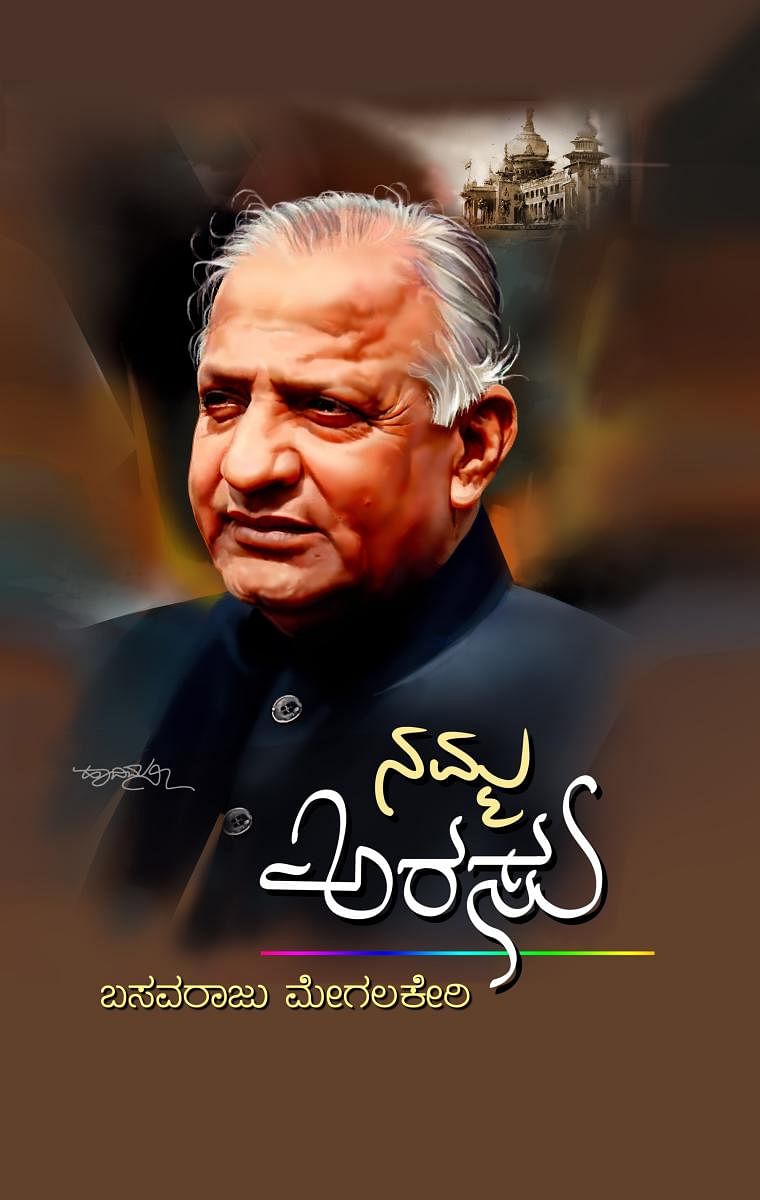

Writing a book on this scale was not easy. In print, it ran into 584 pages. I was in Bengaluru, and Urs’s friends and associates stretched all the way from here till Bidar. I made several trips. I was delighted with the information coming my way.

Revolutionary Chief minister?

Would it be correct to say Urs was the most daring, most revolutionary chief minister of Karnataka? I would say yes. The idea of land reforms was dear to the Congress, and the party had been talking about it since 1962. Two feudal castes dominate Karnataka politics: the Lingayats and the Vokkaligas. It was difficult, if not impossible, for any government to antagonise them. Chief ministers alternated between them, so if anyone tried to implement land reforms, he would be in danger of losing his chair.

Indira’s backing

In 1969, the Congress split into the Syndicate and the Indira factions, and Urs became the convenor of the latter. He was chief minister between 1972 and 1977 and 1978 and 1980.

Mysore state was renamed Karnataka by the Urs government on November 1, 1973. Indira backed the land reforms initiative between 1962-72, and at the end of the 10 years, Urs went ahead and implemented it. It changed everything in Karnataka--its politics, economics, and social relations.

Uttar Pradesh had tried its hand at land distribution, but had faced challenges because of the land-owning Thakurs. Here, Urs had spent 10 years thinking about it. He made N Huchamasti Gowda the revenue minister and Subbayya Shetty the land reforms minister. J H Patel who was in the opposition (Praja Socialist Party) supported Urs. So with a Vokkaliga in Huchamasti Gowda, a Lingayat support in J H Patel and a Bunt in Shetty, he made leaders of the major land-owning castes lead the initiative. That is why it worked.

Urs, hailing from the community, was a landowner himself. He had completed his BSc from Central College in Bengaluru and gone back to his village. While working on his land, he saw the inequality in land ownership. Holdings were small, and tillers only got to keep a small share of what they cultivated. He thought if the tillers became landowners they might be able to lead a better life.

Cushioning the blow

When the land reforms were first announced, Deve Gowda opposed them. He was the leader of the opposition then. He told Urs the trader Settys, Iyengars, and Brahmins would have nowhere to go since they depended on their inherited land holdings for survival. They would become homeless, he said. That did happen. Urs resolved this by giving them a monthly allowance.

In a meeting with minister D B Chandre Gowda, Urs saw a coffee planter wearing a coat with a patch. The planter had fallen on bad days because of the reforms. Urs started giving an allowance to coffee planters also. Today, many things have changed, and anyone can buy land in Karnataka. In 1974, when Urs introduced the Karnataka Land reforms Act, about 7.8 lakh landless families became landlords overnight. Cheluvayya, a labourer at Urs’s farm, got 15 acres. Urs said the reforms should start from him, so no one could point a finger at him.

As a champion of social justice, Urs brought about great transformation. He supported minuscule castes, the religious minorities, and communities deprived of their share in politics, education and employment. He picked people on the margins and brought them into politics. Some examples are Mallikarjun Kharge, Dharam Singh, Veerappa Moily, Veeranna Mattikatti, Margaret Alva, H Vishwanath, M Raghupathy, and T B Jayachandra.

Peanut vendor story

In the 1970s, he picked Hameed Shah, a youth selling peanuts to contest from Shivajinagar. Everybody in the Congress laughed at him but the peanut vendor went on to win by a big margin of 10,000 votes. In Bidar, Urs came to know about B Narayan Rao, from a sheep rearing community. The rich zamindars used to drive the community’s boys away when they took their flock grazing on community land. The young Narayana Rao protested and met Urs. Urs travelled all the way to Bidar, instilled confidence in the community, and made Narayan Rao an MLA. Rao made a name for his honesty and served a term in 2018 during Siddaramiah’s regime. He died in 2020.

Veerappa Moily was an LIC agent when Urs spotted him and gave him a ticket to contest from the Karkala seat. Urs made him a minister in his first term. Moily later went on to become chief minister.

Basava or Urs?

I worked for Lankesh Patrike for 20 years. In 1999, we decided to select a ‘Person of the Millennium’ for Karnataka, inspired by a survey Time magazine had conducted then. We zeroed in on two names: Basavanna and Urs. Lankesh said we should go with Urs. “He changed Karnataka definitively,” Lankesh said.

Corruption question

Urs’s closest associates told him that the people perceived his government as corrupt. Despite his idealism, Urs could do little to curb corruption. He had to keep his MLAs with him, and while they profited from his idea of social justice, they weren’t averse to abandoning him and switching sides. Urs was convinced he needed them at all costs.

When Urs died, he owed a bank Rs 1.3 lakh, and he had taken books on credit from Higginbothams. He also owed money to a petrol bunk, a travel agency and a newspaper vendor. All his dues were paid off by M S Ramaiah, a contractor who later set up an educational empire. Mohan, Urs’s son-in-law, had pledged his land to a land bank and taken a loan. The interest had grown massively. Urs’s daughter Bharati spoke to me about his personal life, and how he was at home. If Urs was corrupt, and by several accounts he was, his immediate family did not benefit from it. One day, at the Chamundeshwari temple in Mysuru, the priest on duty asked him about his gotra. “Karnataka gotra,” Urs said. He had three daughters, and he said after they were married, he and his wife Chikkammanni Urs would return to their village and live the farming life. Another son-in-law, M D Nataraj, brought Urs a bad name.

His decline in politics

After the land reforms, Urs became hugely popular. The media projected Urs as a national leader in 1978. When Indira Gandhi won the election in Chikmagalur, he was honoured by the party in Delhi. But slowly Indira Gandhi became aware of his popularity. Her son Sanjay Gandhi played a role in undermining Urs. She picked many of Urs’s rivals and gave them prominence: Gundu Rao, F M Khan, H M Revanna, K H Srinivas.

S M Krishna wouldn’t talk beyond a point. He just maintained that he, as a Vokkaliga leader, had been told by ‘madam’ (Indira) to support Urs. In 1977, people in Mandya were upset that Cauvery water would be diverted to supply drinking water to Mysuru. A minister then, Krishna had resigned and gone to Mandya to support the protests against Urs. During our conversations, and despite my repeated prompting, Krishna said nothing about this incident.

Two moneybags

His main financial support came from R N Desai, a Lingayat leader from Raichur. He gave Urs all the money without expecting anything in return. Another supporter was the liquor baron Srihari Khoday. Desai and Khoday were two pillars of financial support. Urs used to say the party could use their financial support to help others but it shouldn’t give them power as it would pose a danger to democracy. A capitalist, he believed, could not be a people’s leader.

Urs told Khoday to stop doing business, and spend his money on social causes. Urs was a voracious reader. He read all kinds of books. He had a huge interest in music, the former diplomat Chiranjeev Singh told me. Urs used to attend concerts. He was also a foodie. He used to exercise a lot at a traditional gymnasium, called Garadimane. He always had two dumbbells in the car, besides books.

Objectivity check

Most of Urs’s associates are now in their 80s and 90s. Some people I was interviewing died while the book was in progress. I would go and meet people at the assigned time. Sometimes I got half an hour, sometimes five minutes. Raghupathy couldn’t sit for long because he had knee pain. I spent more than a month and a half with him. At 89, Deve Gowda has a sharp memory. He recalled dates accurately. Some leaders spoke more about themselves, and how they had helped Urs, than about his nature and personality.

Objectivity is a problem when you write a book mainly on the basis of spoken accounts. How do you gauge their credibility? I often felt what Deve Gowda was saying about Urs was not true, but I put it down in the book nevertheless. Readers, I thought, would discern the truth. I called Moily more than 50 times. He kept dodging me. I later heard that Urs had found out something about Moily and confronted him, and so Moily had stopped speaking about Urs. The dates were a challenge. People mixed up dates. I got some references from the Vidhana Soudha library.

I set aside two hours every day for five years, and rewrote and edited my manuscript about 100 times. I worked from 2015 to 2020 to meet people and transcribe everything.

A lost legacy?

During Urs’s time, and in the subsequent decade, Karnataka saw many movements, for students’ and farmers’ causes, for Kannada. But his legacy lies in ruins today. Subsequent governments changed land ownership laws, and ‘land for the tiller’ is an idea that no longer finds favour in India. Many of the poor young men he picked became filthy rich, but their communities remained more or less as backward as they were in his time. In three to four decades, his reforms wore off, but their revolutionary nature had drawn the attention of political thinkers and academics from across the world. Will his idealism inspire change in the future? Perhaps, but the wind is blowing in another direction at the moment.

(Transalted and transcribed by Akash Hedge.)