On the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, it would be a useful undertaking for someone steeped in cinema to make an association between film motifs and the trajectory of the nation.

But before one does this, it should be acknowledged that not all cinemas in India —and there are several — have the same relationship with the nation. In the first place, there are regional language cinemas that address exclusive local identities in a way that the mainstream Hindi film generally does not, even though it was once focused on the Hindi belt.

State and nation

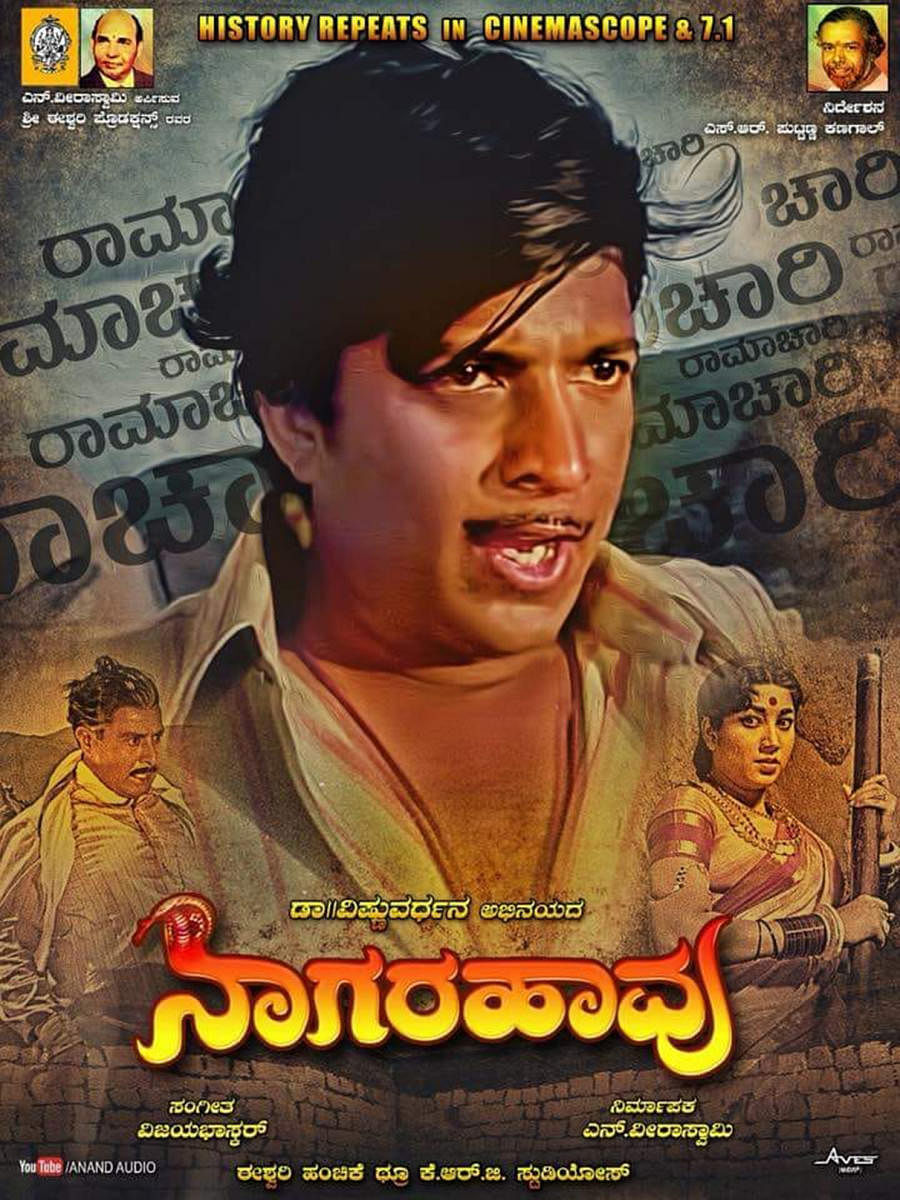

Regional language cinemas are more ambivalent about the nation. To give just an instance from Kannada, in Nagara Haavu (1972) the protagonist reveres his teacher Chamayya but hates his college principal, who he ties up half naked to a pole. Chamayya’s home has pictures of Kannada cultural figures while the principal’s walls have pictures of national leaders like Nehru. The Hindi film is hence more indicative of the nation’s trajectory in the public consciousness, or that of its pan-Indian audiences.

The motifs exhibited are almost always sharply aligned with the socio-political developments at the national level although it will take some decipherment to bring it out. For instance, the court scene is in evidence only after 1947 and the court, representing the moral authority of the independent nation-state, is the sacred site where the truth must be admitted even by those accused. We have in films like Awaara (1951) and CID (1956) the motif of the policeman or judge being judged in court as a token of the law enforcement itself being held to account.

Modernity is a key notion in the 1950s as represented by the city in films like Guru Dutt’s (Aar Paar, 1954) or the dam in Insaan Jaag Utha (1959). Modernity is still an uncertain proposition and in Naya Daur (1957), there is a race between the horse-cart and the bus with the horse-cart winning. Agrarian issues like indebtedness are dealt with in Mother India (1956) and Ganga Jumna (1961), although the discourse implies the punishment of the rebel. There was the Telangana Communist insurrection in the early 1950s and these films covertly invoke that.

The male stars ruling Hindi cinema in this period were Dilip Kumar, who played the existential hero in Babul (1950) and Jogan (1950) when India was confronted by an uncertain ‘freedom’, Raj Kapoor, whose films are preoccupied with poverty and class antagonisms, and Dev Anand, whose ambivalent persona is used to respond to the moral impact of modernity (Baazi, 1951).

China war effect

The cinema up to 1962 is socially responsive but everything changes after that, with the humiliation of the India-China War. Films become romances, which is a way of stepping out of social responsibility (Mere Mehboob, 1963). The ascendancy of Rajendra Kumar may owe to this factor. The escapist entertainment of the period (Waqt, 1965) owes to the same disillusionment with the Nehruvian nation.

Where the city had represented the hopes of modernity, films retreated to hill stations (Woh Kaun Thi?, 1964) and foreign locales (Love in Tokyo, 1966). The relative successes of the 1965 war with Pakistan partly relieved the public gloom in India, then also facing a severe food crisis. The patriotism of Upkar (1967), with its covert anti-Nehru rhetoric, may be taken to reflect upon this. The late 1960s was also the period of the Green Revolution, and Upkar, by dealing with the progressive farmer, also invokes that.

The advent of glam girls

Hindi cinema’s escapism and reliance on vapid romances continue into the early 1970s and Rajesh Khanna (Aradhana, 1969) was to this period what Rajendra Kumar was to an earlier one. The heroines (Sharmila Tagore, Hema Malini) are also more glamorous and decorative than the stronger ones of the 1950s (like Nargis).

Indira Gandhi made a difference to Indian cinema in the 1970s by heralding art and middle cinema through governmental policy as a way of bringing back social responsibility into films. Apart from this, Amitabh and the ‘angry young man’ were also an effect of her radical polemic, the yearnings she awakened among the disadvantaged.

In the 1980s, the nation-state was under siege by divisive forces (notably in Punjab) and the policeman, who had already lost his lustre beginning with the 1960s, is seen at the mercy of gangland lords (Tezaab, 1988). Regional and group identities trump the national one in Ek Duuje Ke Liye (1981), and rape is a motif, equated in Insaaf Ka Tarazu (1980), with ‘dishonouring the nation’.

Liberalisation themes

Much has been written about 1990s cinema after liberalisation (Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, 1994) when the state was no longer featured through its institutions. If it was, it was equated with private enterprise, since it was as indifferent to legality (Satya, 1998). The patriotism of the 1990s (1942: A Love Story, Border, Lagaan) is also different. Conflict with an exclusive external enemy replaces the concurrent internal conflict of Upkar. Shahrukh Khan’s early persona suggests someone amoral because of the uncertainties brought about by the demise of the moral Nehruvian state.

The global age transformed cinema once again through the multiplex revolution, when audience segments could be targeted. What came to be called ‘hatke’ cinema or ‘New Bollywood’ are simply the targeting of Anglophone urban Indians (with spending power) by films like 3 Idiots (2009) and Peepli Live (2010), the latter reducing farmers to comic figures. Salman Khan is the single non-English speaking hero in this scenario. Sports films eulogise corporate endorsements (Iqbal, 2005) while sneering at government incentives (Chak de India, 2007).

Rise of the south

The most recent transformation is the new wave of Hindu patriotism unleashed by right-wing affiliates. The decline of the male star and resounding flops from erstwhile matinee idols suggests the end of multiple narratives to represent the trajectory of the nation. If there is a sense that the nation has only one meaning, Bollywood becomes redundant, making way for regional films to step into the space in dubbed Hindi versions.

Hindi cinema was once truly national, as can be seen from the above, but with a single narrative of the nation gradually prevailing, the chaos and noise of regional cinema (KGF, RRR) can be understood as the polyphony resisting it. Regardless of how deafening these films are, I still do not hesitate to welcome them.

(The author is a well-known film critic.)