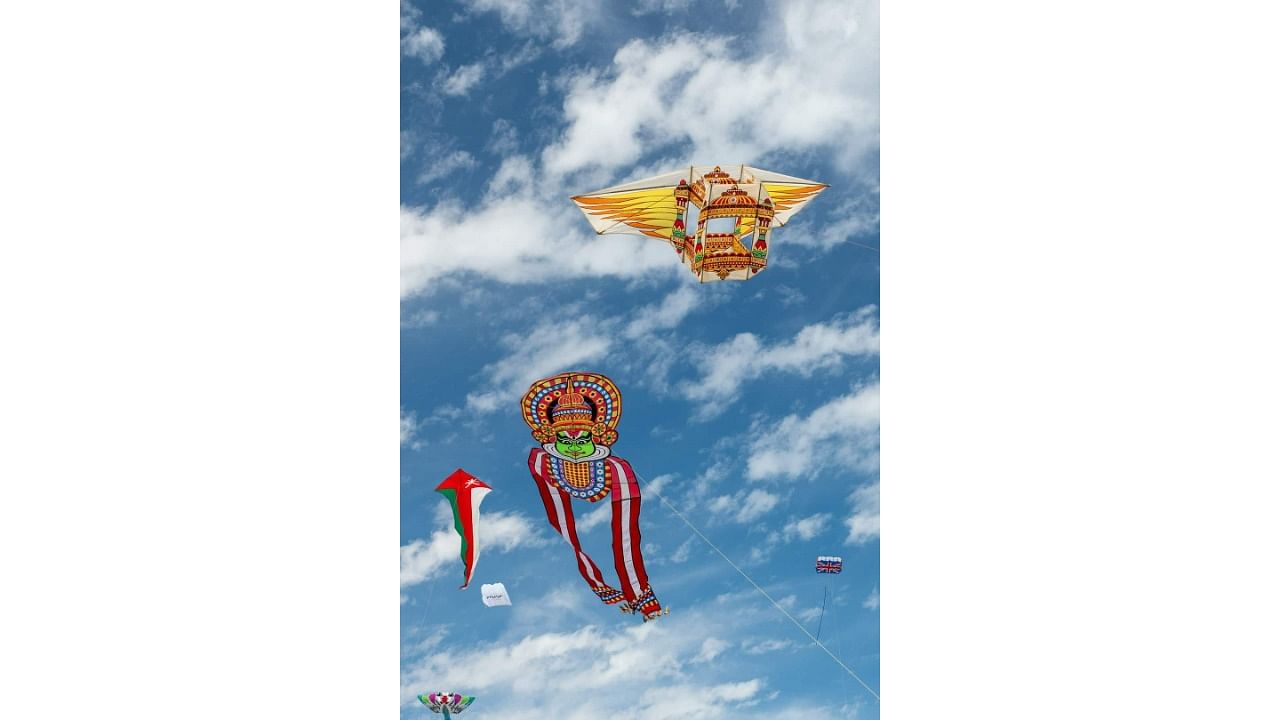

Kites made by Team Mangalore take to the skies at a kite festival.

Credit: Special arrangement

As in other parts of the country, the arrival of Uttarayana, or Sankranti, brings with it national and international kite festivals in the towns of Karnataka. While the blue sky, dotted with colourful shows or fancy kites, is what grabs our gaze instantly at these festivals, little do we realise that kites are beyond pieces of paper and spars.

Right from designing, cutting, pasting and stitching to tying the kite lines considering principles of aerodynamics, each kite is a combination of art, craft and science.

There are just a few artisans in Karnataka who custom-make such kites against orders, as most kitists make them on their own.

Showing the 36-foot-long ‘Kathakali’ kite being recreated in Mangaluru, Sarvesh Rao explains that he leads ‘Team Mangalore’, a group of kite lovers from the region. Back in 2006, a similar design created by the team had entered the Limca Book of Records for being the largest kite in India. This year, the team recreated it, as the old one had faded after years of use. Nearly 8 to 10 people toiled for over a month to recreate the kite.

“The kite is completely handmade using imported ripstop nylon fabric and bamboo spars. It costs nearly Rs 50,000,” says Rao.

He adds that their kites usually depict aspects of Indian culture, including Bharatanatyam, Yakshagana, Bhootakola, Pushpak Vimaan and Garudas, as they are in high demand at international kite festivals.

Every night, Rao, along with his team comprising of working professionals in various fields, sits in a hall on the third floor of his house in Mangaluru. Here, these kites begin their journey from the ground.

Dinesh Holla, a kite designer associated with Team Mangalore explains: “First, we design the kite considering the shape, colour scheme and proportion. Then, a paper print of the design is stuck to the ground and a background cloth is cut as per the outline. Following this, small pieces of colourful ripstop fabric are stuck and stitched to the background cloth as per the design. Once ready, the background cloth is detached.”

“It is sheer hard work as every small piece needs to be stitched intricately,” Holla adds.

Once the fabric kite is ready, bamboo sticks are stripped, trimmed and coupled (joined to the fabric) to form a frame (or spar). Then comes the role of a science expert, who plans on attaching the bridle. This is followed by attaching kite lines made of nylon, fibre or other materials.

Inspired designs

Another kite-flying enthusiast, Sandesh Kaddi from Belagavi, who has engaged in the hobby for more than 15 years, specialises in making geometric-shaped kites.

Drawing inspiration from floor tiles, glass work and other day-to-day objects, Kaddi transfers the design onto a graph sheet and then stitches the kite using locally available materials like those used to make umbrellas and parachutes. He also makes miniature kites (4x4 inches) using paper and bamboo spars.

“Making kites is not taught in schools and most kite-flyers from Karnataka learn the skills through trial and error,” says Kaddi, a businessman by profession. He learnt kite-making from the internet and by interacting with other kite designers.

Earlier, kites were generally flown using ‘manjha’, string coated with glass or other abrasives. This resulted in the death of thousands of birds every year. It has been banned by the National Green Tribunal.

Kaddi says a majority of professional kite-flyers from Karnataka do not use manjha anymore and instead use high-tensile strings made of varied materials.

V K Rao, a master kite-flyer from Karnataka, says he has been increasingly using kites to give social awareness messages. The kitist has flown kites on several national and international platforms including for television and film shoots.

His kites carry messages on voting rights, yoga and more. He prints his message on canvas in a large font that is visible from far-off distances.

Festival season

Kite-flying traditionally comes alive during the Hindu month of Aashada, in June-July, when the wind speed is conducive. The trend of organising kite festivals during Uttarayana has trickled down from northern Indian states and Gujarat.

In the villages of southern Karnataka, kite-flying is ritualistically arranged on Aashada Ekadashi. “On that day, kite-flyers fast. The kites that they fly do not have elaborate designs and are simple,” says V K Rao.

Elaborating on the unique kites of south Karnataka, Prasanna Kandvara of the Doddaballapura Galipata Kala Sangha says that they heat strips of bamboo, smoothen them and tie them to form a frame. They then cover it with paper or plastic. The uniqueness of these kites lies in the fact that they paint elaborate pictures of gods, goddesses, cartoons, birds, animals and film stars on them.

During Aashada, each expert from their group paints around 300 to 400 such kites, he says.

Sadir Hussain, who has been making kites at his home in Shivaji Nagar in Bengaluru for the last 20 years, says he learnt the skill from his father. Every year, he makes around 15,000 fighter kites that range from Rs 1 to Rs 50, and also creates show kites against orders. Kites with eagle and cartoon designs are the most popular, he adds.

However, professional kite-makers are dwindling in Bengaluru, says Hussain. From 20 to 30 kite-makers a decade ago, only four are left now, he explains. “Kite-making can grow into a craft industry just like in Gujarat, if the government provides a platform to sell kites,” says Hussain.

Currently, the artisans are only busy during the peak season, forcing them to think of alternative jobs.

Sarvesh Rao shares a similar concern. He feels that kite-making is dying a slow death as the art is not being passed on to the younger generation. Their group has conducted some workshops on kite-making for children, but he feels the younger generation has not experienced the joy of sports like kite-flying.