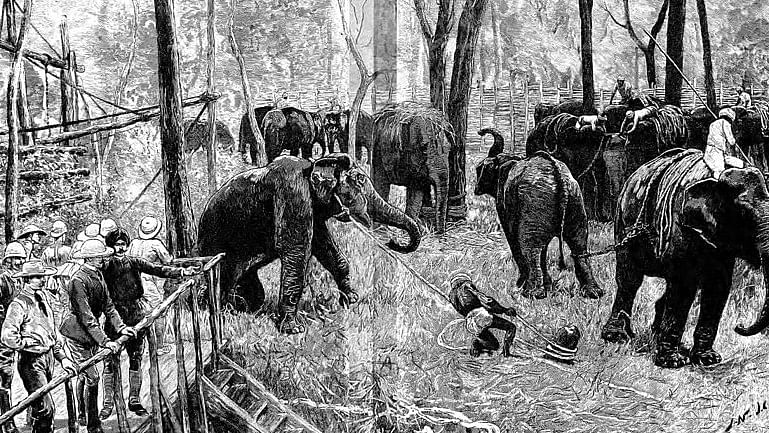

An illustration of G P Sanderson, King Albert Victor and the Maharaja of Mysore watching a 'khedda' operation. Photo

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Accounts of 19th-century princely Mysore offer interesting details about the state’s natural resources — particularly its jungles. Hunting for game (shikar), tracking animals, khedda operations and the lives of people living in the forests are all well-documented. Some officials in the forest establishment have also left day-to-day diaries. The narratives of British naturalist G P Sanderson, for instance, throw much light on these aspects.

The name G P Sanderson is synonymous with khedda operations in the second half of the 19th century in princely Mysore. Khedda first began during the time of Hyder Ali in the Kakanakote region. But due to the cost of operation and lack of infrastructure, it was gradually given up.

In September 1873, with the arrival of G P Sanderson at Chamarajanagar, the capturing of wild elephants began to be commissioned. Due to his interest in hunting, the naturalist had developed an expertise in capturing wild animals. He was accompanied by the mahouts of the Maharaja (Chamaraja X).

Sanderson came up with a new system to capture wild elephants and subsequently train them for forestry work. His method involved driving herds into a ‘khedda’ or a fenced enclosure, instead of trapping them in pits.

In 1874, the Commissionerate established the Department of Khedda to capture wild elephants in Chamarajanagar. G P Sanderson soon began to supervise these operations.

In his book ‘Thirteen Years Among the Wild Beasts of India’, Sanderson narrates his experiences.

The team primarily worked in the regions now known as Chikkamole and Doddamole, located in Chamarajanagar taluk. Elephants visited these places frequently. Many times, they used to emerge from the nearby B R Hills. In Sanderson’s accounts, we come across references to Honnuhole river, Ramasamudra lake and several tribal hamlets located in the region. There are also names of locals who were trained by him in capturing and taming wild elephants.

By the time the khedda department was established, Sanderson was already well-versed in the operations and his knowledge of the region. With the help of the locals, he had built a small house consisting of a drawing room, dining and a sit-out surrounded by a trench and fence. Gradually, his acquaintance grew with the local people, who traditionally worked in salt-making.

Training the community

Sanderson has also recorded details about the character and behaviour of elephants in captivity. His book includes a fascinating pencil drawing which marks out the routes of elephants, driven from and to different directions.

Both in Chikkamole and Doddamole, Sanderson worked to share his knowledge with the locals. He taught them to use different types of equipment to catch elephants. He also taught them the art of riding tamed elephants.

In the first drive, 16 male elephants of different sizes, including 3 large tuskers, three ‘mucknas’ (or tuskless males), 30 females and nine calves were caught. Among them, 25 were auctioned and the rest were sent to different establishments. The experiment, having succeeded, was further expanded.

Sanderson also describes his experiences catching elephants at Chittagong, and shares these stories with his companions upon his return to Chamarajanagar.

The new area of operation was the Kakanakote region, in the present-day Mysuru district. A novel feature of the operations here was the extensive use of telegraph. A line was erected through the jungle, spanning 36 miles from Kakanakote to Hunsur, where there was a telegraph station with an all-India network.

Over the years, Sanderson came to be named the ‘hathi king’ or ‘elephant king’ by the press for his exploits in developing new methods and training elephants. Today, his memoirs take us to a different time, one of daring khedda operations.