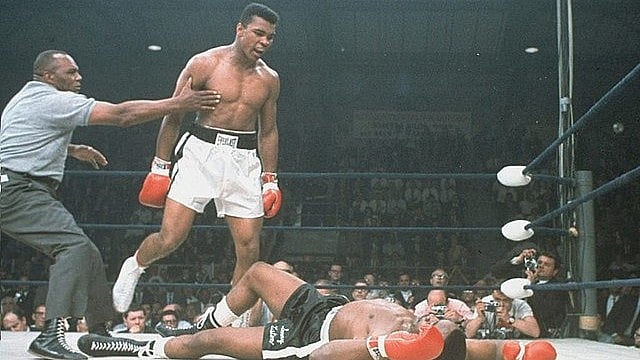

Muhammad Ali.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Impossible is just a big word thrown around by small men who find it easier to live in the world they’ve been given than to explore the power they have to change it. Impossible is not a fact. It’s an opinion. Impossible is not a declaration. It’s a dare. Impossible is potential. Impossible is temporary. Impossible is nothing.”

- Muhammad Ali

I’m a little wary of people who blow their own trumpet loudly and often, so it was with mixed feelings of awe and a sort of distaste that I waited for Muhammad Ali. Three-time winner of the World heavyweight title and the winner of 56 of the 61 professional fights of his career, Ali was a force to reckon with. Ah… there he was. The stooped posture and shuffling steps that he developed towards the end of his life made my heart soften — this was not the man who declared that he would “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. The hands can’t hit what the eyes can’t see. Now you see me, now you don’t” boxer of legend. It was a man old beyond his years and stricken with Parkinson’s. “Thank you, sir, for agreeing to meet with me,” I said. Ali nodded and smiled as he sat down. “Can we start with you telling us something about your early life? You weren’t born Mohammed Ali, were you?” “My birth name was Cassius Clay. I was named after a white farmer who emancipated 40 slaves. In the 50s segregation and slavery were a ‘natural’ phenomena in the American south. My father painted billboards and my mother worked as a domestic help. As a child, I saw all the white objects and people in literature, in media and even in household products and I wondered why black people weren’t shown like that.”

Ah… there was the activist Ali that we knew so well in his later days. But we were getting ahead of ourselves. “Yes, I’d love to hear more on that but can you first tell us how you got into boxing?” “A Louisville policeman, Joe Martin saw some potential in me and began to tutor me in boxing at the age of 12. I think I caught people’s attention in the early days more because of my personality than because of my boxing,” he laughed. “I wasn’t by any stretch of imagination humble. And I know that that put off some people who thought that a black man had no right to be so outrageously defiant. I told people that I was the greatest and people believed it! I did, however, win the Olympic gold in 1960 but it was in 1964 that the game that stunned everyone came. I challenged Sonny Liston for the heavyweight championship of the world. And I won! That same year, I accepted the teachings of the Nation of Islam and changed my name.”

“Why did you refuse to join the army? Wasn’t it unpatriotic?” I asked rather disingenuously. “Unless you have a very good reason to kill, war is wrong,” said Ali, repeating what he had said at the time. Ali was banned from boxing and returned to the ring only in 1970. He was no longer as fast as he once was and in 1971, he lost to Joe Frazier who was then the heavy weight champion. “How did it feel when you lost to Frazier?” I asked. Ali shrugged. “At the end of the day, It’s just a job. Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up. You shouldn’t fear failure,” he went on. “We must take risks to progress in life. When you saw me in the boxing ring fighting, it wasn’t just so I could beat my opponent. My fighting had a purpose. I had to be successful in order to get people to listen to the things I had to say... I hoped to inspire others to take control of their lives and to live with pride and self-determination.”

“There was no point to an Olympic medal if I was still denied service at a diner.” I remembered that this had happened right after the Olympic win. “You see, I was the Louisville Lip, no doubt, but I want to be remembered as someone who spoke the unflinching truth to his generation and became a symbol of dignity to all African Americans.” “Yes, your charm and wit are legendary,” I said. “I especially remember that interview where you countered the argument that not all white people are racists.” Ali chuckled. “Yes. What?! I’m going to forget the 400 years of lynching and killing and raping and depriving my people of freedom and justice and equality… and I’m gonna look at two or three white people who are trying to do right and ignore the million trying to kill me? I’m not that big of a fool,”

“I think you made your point loud and clear,” I said with a grin. It was certainly louder and clearer than the myriad “It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am.” statements.