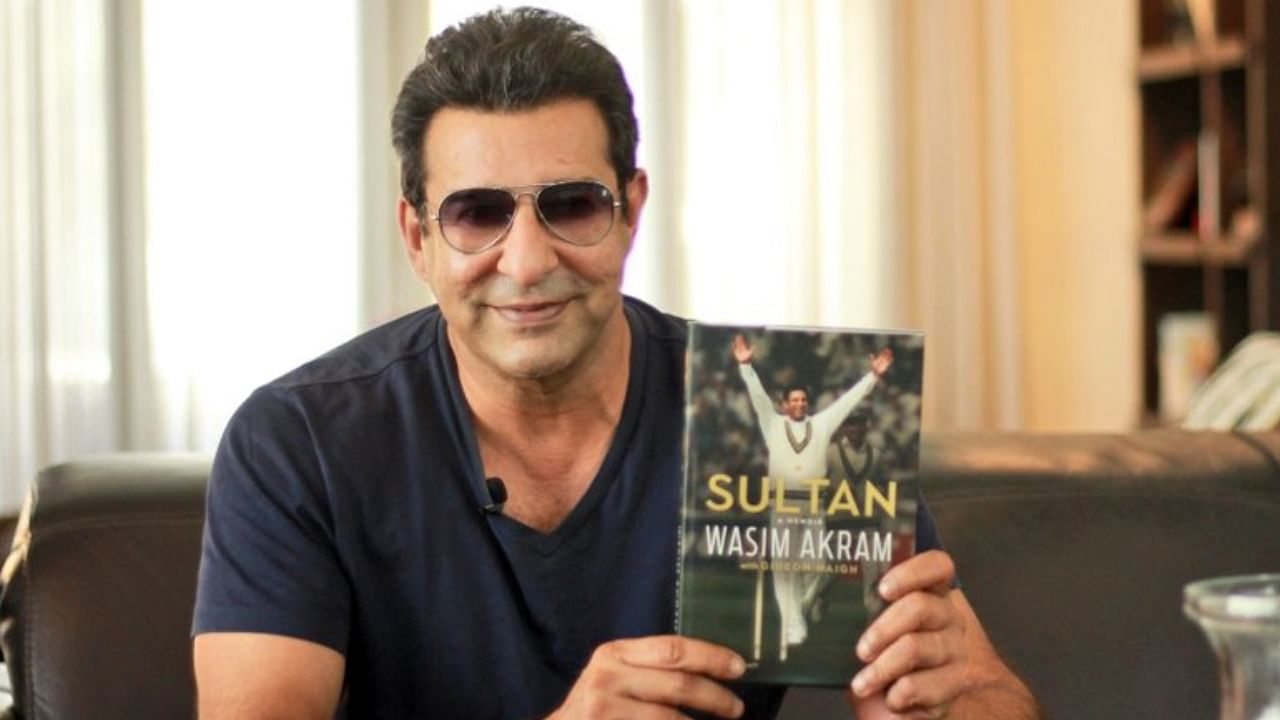

Wasim Akram's startling revelation about his cocaine addiction has shown that even the best of athletes are vulnerable to drug abuse, even more so when they don't plan for life post-retirement.

Speaking to a Pakistani sports channel on the revelations he made in his book, Akram, arguably the best left-arm pacer to have played the game, said he was clueless about his future after he retired from the game and that perhaps pushed him towards drugs.

Akram's case is a lesson for all current athletes on how to prepare for life after they are done with the game. An athlete like Akram might be invincible in what he does on the field but he remains human after all.

Gayatri Vartak, a sports psychologist who works with elite Indian sportspersons including cricketers, says an active athlete is also at risk of falling prey to drug abuse and not just someone who has left the professional sport.

Former Zimbabwe captain Brendon Taylor's name comes to mind when one thinks of an active cricketer admitting to cocaine use.

Former England cricketer Chris Lewis had got 13 years in jail way back in 2009 for cocaine smuggling though he denied having used the substance. He had admitted that he smoked cannabis.

Former India cricketer L Sivaramakrishnan and Australian legend Shane Warne used to smoke but were not into drugs.

Vartak delved deep into possible reasons that lure athletes, both present and former, to the menace of drugs.

Also Read: The Suryakumar phenomenon

"What happens is as an elite sportsperson or a high achiever, there is a lot happening in your life in terms of training, travelling, tournaments and suddenly when you quit sport it leaves a big void and athletes often find it hard to deal with that void.

"...because sometimes they have not thought about how to replace that void. That is what really causes this. So retirement has to be planned first of all. A lot of times it is not planned at all," Vartak, who is also a former badminton player, told PTI.

By his own admission, Akram did not plan for retirement and had he done that, he might not have developed a cocaine addiction.

"I did not know what to do after retirement. I wasn't a businessman, I wasn't an Indian cricketer who had enough financial security and could relax.

"I was worried about my future and then company matters a lot but in the end, if I have to blame someone, I would only blame myself," the great left-arm pacer told A Sports.

Like Akram, life post-retirement can be a rude shock for a lot of athletes and therefore the pressing need to prepare them for the road ahead.

Vartak feels a lot of time is spent on the timing of retirement but often not enough attention is paid to the transition from an athlete to an ex-athlete.

"Retirement is obviously going in an athlete's mind for a while but the conversation is always about the timing of the retirement. It has to be more than just the timing, it has to be about how you are going to deal with a change in identity.

"From an active cricketer to an ex-cricketer. What are the changes that are going to happen in your everyday life? What are the new routines you are going to form? If you do that, the chance of having that void reduces drastically and hence the risky behaviour associated with it," she said.

Besides planning or the lack of it, an athlete's surroundings also play a big role. A cricketer is steeped in the dressing room environment. In his playing days, he spends most of his time, on and off the field, with his teammates but once he exits those surroundings, he could feel lost.

"If you specialise in one thing over long and your peer group, at least in cricket, becomes your teammates. When you don't play, those teammates don't become a part of your life because some of them are still playing and some of them live away, the new social circle doesn't really get formed.

"As an athlete, you are also a little wary of people who come around you, you are not sure what their agenda is. All of this contributes to loneliness and then it could lead to risky behaviour," Vartak explained.

An active athlete too is at the risk of losing their way and end up with drug abuse, she reckoned.

"At the elite level, you have a lot of ups and downs. When you are playing well and everything is working for you but sometimes you lose the purpose of what you are doing. The why is not as clear as you would like it to be and when there is plenty of time, you end up indulging."

Glamour associated with a top athlete's life can also be a contributor as not all are prepared to move away from the spotlight.

"There is a big trade-off with your athletic identity. People identify you with that all your life and suddenly now you are an ex-athlete. The top 10 per cent can still carry on with an ex-athlete tag but not everybody can.

"So what do you replace that with? The replacement of identity has to be thought. Planning on financial, professional and personal aspects has to be thought of (once you start thinking of retirement)."

Mental health of top sportspersons including cricketers is spoken about a lot more now compared to a decade ago. There is less social stigma attached to it.

The career span of an athlete is much shorter than that of a common man who doesn't have to retire before 60, making them equally vulnerable to drug abuse if not more.

"A common man's retirement age is around 55 while an athlete's retirement age is much earlier so they have a massive number of years left in their lives to do something productive and a lot of their peers are not retiring with them as not all are of the same age. That is the difference that makes it harder (for athletes)," added Vartak.