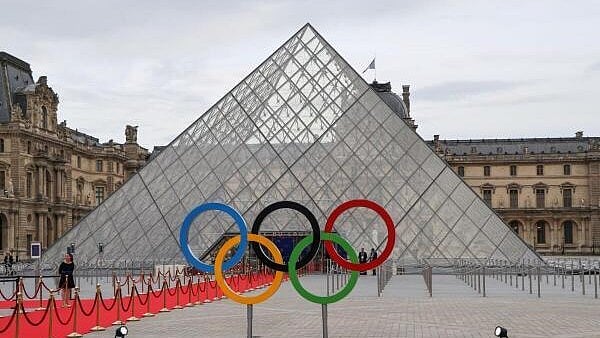

A view shows Olympic Rings set by the Pyramide du Louvre.

Credit: Reuters Photo

Paris: There is a glorious folly to the Paris Olympics, the first in the city since 1924, as if France in its perennial revolutionary ardor took a century to ponder something unimaginable, the transformation of a great city into a stadium.

The heart of Paris has fallen silent in preparation for the opening ceremony Friday, when a flotilla will usher thousands of athletes down the Seine, under the low-slung bridges where lovers like to linger. Not since the Covid-19 pandemic has the city been so still or so constrained.

From the Pont d'Austerlitz in the east to the Pont Mirabeau in the west, roads are closed; newly built stands for spectators line the riverbanks; fences enclose sidewalks; and residents need police-issued QR codes to reach their homes. The golden cherubs, nymphs and winged horses of the Pont Alexandre III gaze out on metal bleachers and possess of police.

The Olympic project is almost unthinkable in its audacity, and a major security headache, but then again, the Eiffel Tower would never have risen above Paris in 1889 if the many naysayers had prevailed. As it went up for the Paris World Fair, Guy de Maupassant called the tower a "giant hideous skeleton" that had driven him out of Paris.

Now, between its first and second floors, five giant Olympic rings -- in blue, yellow, black, green and red -- adorn the tower. They glow at night over the Champ de Mars Park, where the beach volleyball competition will be held. Nearby flows the Seine, beautified at a cost of about $1.5 billion and clean enough, it is said, for several Olympic events, including two 10-kilometer swims and the triathlon.

Swimming in the Seine was banned 101 years ago. All things come to an end. These Games, at a cost of about $4.75 billion, were conceived to be transformative in a lasting, environmentally conscious way. "We wanted a dash of revolution, something the French would look back at with pride," said Tony Estanguet, the head of the Paris Olympics committee.

Paris has seen its share of upheaval over the centuries. To walk its streets is to be accompanied by history and to be ambushed from time to time, even after many years, by some previously unnoticed inflection of beauty.

To be a "flâneur", poorly translatable as a wanderer, is a particularly Parisian state, capturing the random meandering of the observer who is entranced by the city and its people. "America is my country and Paris is my hometown," said Gertrude Stein, the novelist and art collector.

Wonderment is a common condition here. The way the light falls -- on a golden dome, or through the leaves of the plane trees, or on the limestone walls of a handsome boulevard, or across the shimmering water of the Seine at dusk -- stops visitors in their tracks. The City of Light is also the city of etched shadows ever redrawing its lines.

In summer, crowds of young people gather on the riverbank. They drink wine and beer. They play music. Sightseeing boats glide past, carrying tourists who wave and are waved at. The sensual conviviality that has made "Paris" and "romance" inseparable words is palpable.

Among the revelers, there is generally a reader or two holding a book, isolating earbuds in place, lost in solitary musing. Paris is a city where books are prized and authors celebrated in prominent posters and other ads that in the United States would be reserved for Hollywood movies.

It is also a city of formality and refuge. Quiet spaces abut architectural grandeur. You are never far from magnificence, perhaps most extravagantly illustrated by Napoleon Bonaparte's tomb at the Hôtel des Invalides, but never far, either, from an unsuspected covered arcade, like the Passage Verdeau, that snakes from a Grand Boulevard into an intimate world. Hidden enclaves like the little St. Vincent Cemetery in Montmartre are part of the ever-renewed mystery of the city.

Even in the approaches to the Grand Palais, built just off the Avenue des Champs-Élysées for the Paris World Fair of 1900, gravel paths lead through secluded greenery. The immense palace, with its classical stone facade and vaulted roof of iron, steel and glass, will host the taekwondo and fencing events. It seems a suitable setting for the saber.

A little farther down, at the Place de la Concorde, athletes in three-a-side basketball, break dancing (known in the Olympics as break) and BMX freestyle (motocross stunt riders) will compete for gold medals. Guests at the adjacent Crillon Hotel, the ne plus ultra of Paris luxury, may not be amused.

Of course, central Paris is not all of Paris. Much of the Games will take place in Seine-Saint-Denis, a densely populated neighborhood north of the city blighted by poverty, crime and the faltering integration of mainly North African immigrants, deprived of decent schools and opportunity.

It is also a vibrant melting pot and a testament to France's growing diversity. The Olympic Village will be housed there, and a new 5,000-seat Aquatics Center. A clean river and a revitalized Seine-Saint-Denis integrated into a "Grand Paris" are two of the core aspirations of the Games.

They are noble ambitions, but in France, seeing is believing. Clashes over immigration policy in places like Seine-Saint-Denis have been one of the factors poisoning French politics of late, leaving the country deadlocked and with no more than a caretaker government as the Games begin.

Of course, malaise is nothing new in France; in fact, it's a French word for a long-term national condition.

I see this newly birthed stadium city through many-layered memory. There are places you come to at an impressionable age that will not leave you. Almost a half-century ago, I lived as a student in a tiny apartment at the bottom of the Rue Mouffetard on the Left Bank. I was studying French and giving English lessons three times a week in a high school in a southern suburb famous principally for its prison.

I would return in the early evening and wander around the Mouffetard market -- the mackerel glistening on their bed of ice, the serried ranks of eggplant, the raucous invitations to buy the last of the silvery sardines for a song. Acrid smoke from Gauloise cigarettes swirled in the wintry air. My single window on the city offered inexhaustible distraction.

The smoke has gone, largely, from Paris, and there are fewer bracing glasses of sauvignon blanc being served midmorning. English has made a devastating assault on French, with "le sharing" and "le bashing" among my recent least favorites.

Yet the unique texture of Paris endures -- that web of zinc roofs and dormer windows and chimney pots and black-grilled balconies and peeling off-white shutters and cobblestone streets and gravel pathways and flat-topped pollarded trees and inviting bistros with names like Chez Ginette that make it easy for movie directors like Wes Anderson to long to be French or even imagine they are.

Food still occupies a central place in Paris. Lunch remains an honored ritual, despite the encroachment of fast food. The advice of A J Liebling, the New Yorker writer and gourmand of Paris, remains useful: "Each day brings only two opportunities for fieldwork, and they are not to be wasted minimizing the intake of cholesterol."

Nothing is more Parisian than the hill of Montmartre, topped by the white-domed Basilique du Sacré-Coeur, besieged by tourists taking as many selfies as photographs of the splendid panorama beneath them. Here the likes of Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani lived, and here cyclists will climb repeatedly during the road-cycling Olympic event.

The Rue Lepic winds down the hill. At one of its curves stands Au Virage Lepic, or the Lepic Bend, a small restaurant with tables set close together.

"What we need from the Olympics is gaiety!" said Maria Leite, the owner of the restaurant, who complained that business was way down as tourists shied away from the Olympics and accompanying restrictions.

Michel Thiriet, 78, a habitué of the restaurant, was lunching alone on steak tartare. I asked him if he was enthused by the Olympics. No, he said, echoing the sentiment of many Parisians who have fled what they see as the life-complicating takeover of their city. For Thiriet, it was all a form of "megalomania."

He said he was a retired movie camera operator. And what, I wondered, does he do now? "I am awaiting death with tranquility," he said. Fierce realism is another characteristic of a city that has seen it all.

A poll last week by IFOP, a market-research group, found that 36% of French people were indifferent to the Games and 27% anxious about them. That may well change once it all begins. The Olympics will usher an expected 11.3 million visitors through the history of France, to the Palace of Versailles for equestrian events amid the urns and statuary and formal symmetry of the Gardens, where French royals once disported themselves before being decapitated in the Revolution of 1789.

At the Hôtel de Ville, or City Hall, more elaborate than many a royal palace, the Olympic marathon will begin. It was here, on Aug. 25, 1944, in a Paris just liberated from the Nazis, that Gen. Charles de Gaulle made one of his most memorable speeches. "Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris freed!" he said, before attributing the liberation to "the only France, the true France, the eternal France."

Nearby, on the Île de la Cité, stands the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, its spire now replaced after the fire of 2019 but still encased in scaffolding as its restoration nears completion. Beyond it, at the east end of the island, is the Memorial to the Martyrs of Deportation, among them the 75,000 Jews killed in Nazi camps by the other France, that of the collaborationist Vichy regime, against which de Gaulle fought and of which he said nothing in his speech.

In some ways, the very survival of Paris, marked at different times by religious wars, revolutionary terror and murderous hatred, is a miracle. In the small garden under the Pont Neuf, there is a plaque that commemorates the thousands of Protestants "assassinated because of their religion" in the city in August 1572. I never fail to stop there when I can.

From beneath the willows at the western edge of the Île de la Cité, which points its prow down the river, the city stretches away past the Louvre toward the faintly silhouetted hills of the suburb of St. Cloud. Many have asked, as many of the Olympic athletes no doubt will as they sail toward the Eiffel Tower and Trocadéro: What is this magical harmony of Paris?

It is grace and it is calm and it is consolation for the weary, but perhaps in the end it cannot be pinpointed, and that is of the nature of magic. "Fluctuat nec mergitur," says the city's motto. "She is rocked by the waves but does not sink." With luck, the Olympics will raise Paris still higher and, in a world marked by wars, offer reconciliation and peace.