Every experiment sets out to prove a hypothesis, and Tom Brady formulated an outrageous one last March, when he chose to flee the empire he helped build in New England to sign with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Going from a franchise with whom he had won six titles to one that had won a total of six playoff games, Brady believed that, at age 43, he could master a new offense, acclimate to a new team and conquer a new conference, all while the coronavirus pandemic limited in-person activity.

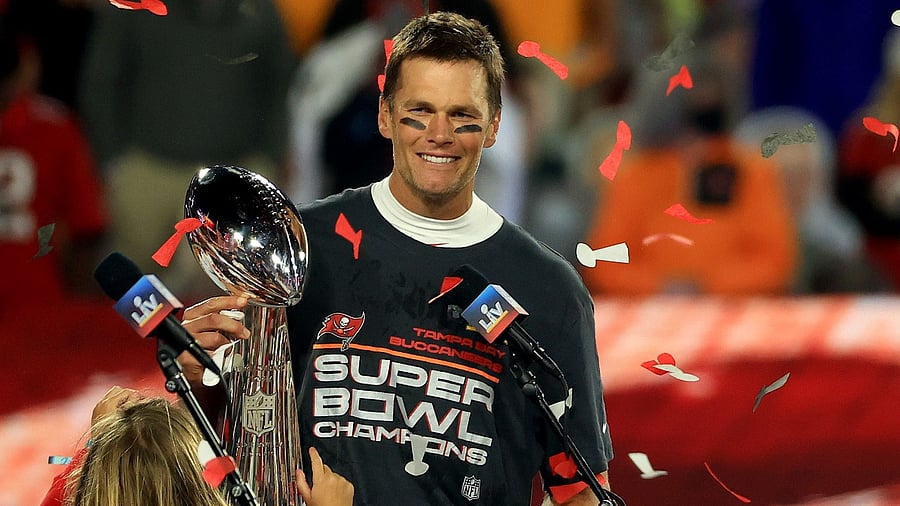

The most precious of NFL baubles is the Super Bowl ring, and each of Brady’s — seven, the latest secured on Sunday night — reinforce an indomitable truth: When he has something to prove, he is just about unbeatable.

Flicking away the Kansas City Chiefs’ dynastic aspirations and the quarterback who poses the most credible threat to someday matching him, Brady guided the Buccaneers to a 31-9 romp that recalibrated his own standard for greatness.

In winning his seventh title — more than any NFL franchise, more than John Elway and his boyhood idol, Joe Montana, combined, more than Michael Jordan in the NBA — Brady, backed by a ferocious defense that swarmed Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes, threw three touchdown passes to deliver the Buccaneers franchise’s second championship in front of a partisan crowd at their home field, Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Florida.

This Super Bowl win was, for Brady, undoubtedly his hardest, his sweetest and his strangest, too, captured at the end of the most improbable, unbelievable season in NFL history. The coronavirus pandemic upended schedules, postponed games and infected more than 700 players, coaches and staff — as well as Brady’s parents, Tom Sr. and Galynn — and it tempered the spectacle surrounding the country’s most-watched sporting event.

For this untidy heap of a season even to reach Sunday’s capstone, it was as if the NFL struck a cosmic bargain: In exchange for ploughing through a full 256-game slate — and without creating a closed environment in which to play — it would be granted the most tantalizing quarterback matchup in the Super Bowl era, Brady and Mahomes, the best of all-time against the best of this time.

Never before had the last two Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks faced each other, and in some circles the game had been distilled in rather crude, and imprecise, terms, as a referendum on each of their legacies — as if Brady’s would be tarnished with a defeat, or if four seasons into Mahomes’ glorious career his was somehow linked to the outcome.

Mahomes had won 16 of 17 starts this season, but he and his team collapsed amid a deluge of penalties, drops and pressure from the Buccaneers, who, exploiting the Chiefs’ diluted offensive line, revelled in it, inflicted it, even embraced it. At halftime, Mahomes had 67 yards and Kansas City trailed by 15 points, tied for its largest deficit of the Mahomes era.

The only other time Mahomes’ team had been behind by that many points across the last three seasons occurred in October 2018, in a loss to Brady at New England. Brady spent two decades there, where he and Bill Belichick were the immovable objects of the postseason, winning six championships as the most famous quarterback-coach tandem of this generation.

What Belichick must have been wondering Sunday night as New England wept, watching Brady throw each touchdown to a former Patriots teammate — two to Rob Gronkowski, who came out of retirement for the chance to play again with his old pal, and one, just before halftime, to Antonio Brown.

Brady’s time in New England will forever be a part of him, but now he wears a skull and crossbones on his helmet, can dress in shorts to practice in the winter and reports to a 68-year-old coach, Bruce Arians, who, coming out of retirement to coach the Buccaneers, represents the stylistic antithesis of Belichick. When asked recently about pursuing Brady during the offseason, Arians responded with a rhetorical question: “Do you sit and live in a closet trying to be safe, or are you going to have some fun?”

Brady’s arrival in Tampa reflected a certain harmonic convergence, a confluence of foresight, audacity and serendipity largely alien to the Buccaneers, who hadn’t won a playoff game since capturing their only title in the 2002 season.

Their quest was nicknamed Operation Shoeless Joe Jackson, a wink to the prophesy from the movie “Field of Dreams”: “If you build it, they will come.” Brady valued how general manager Jason Licht had assembled a team that solved problems around him instead of asking him to solve them himself.

The Buccaneers loaded up on playmaking receivers, linebackers who excelled in coverage and aggressive defensive backs who matured as the season progressed. Before it even started, their cornerbacks coach, Kevin Ross, wrote on a board all the quarterbacks they would be facing — Matt Ryan, Drew Brees, Aaron Rodgers and Mahomes, who torched them in Week 12 for 462 yards and three touchdowns. But that defeat proved to be an inflection point for the Buccaneers, who had moonwalked through the first three months, going 7-5, shuffling forward at the same time as they drifted backward.

They closed the season by winning their last four, then defeated three consecutive division champions — and two of Brady’s elite quarterbacking peers, Brees and Rodgers — on the road to advance to their first Super Bowl since the 2002 season, when they throttled the Raiders. That team, like this one, teemed with defensive talent and needed an outsider, coach Jon Gruden, to synthesize it into a champion. Brady conferred the Buccaneers with hope and credibility and possibility.

In a measure of Brady’s sustained excellence, consider that he has now quarterbacked not only the most recent team to win consecutive Super Bowls, with New England after the 2003 and 2004 seasons, but also the last two to ruin repeat bids. If a classic defensive play foiled Seattle after the 2014 season, then it was a comprehensive effort that smothered the Chiefs, with the Buccaneers forcing two turnovers and preventing Kansas City from scoring even a touchdown.

Brady ousted three Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks during this championship run, but unlike Brees and Rodgers, Mahomes, 25, has plenty of seasons remaining to flaunt his exceptional talent. The league is now Mahomes’, and with the Chiefs’ inventive coaching staff and nucleus of bountiful young talent, his time will very likely come again.

But the championship belongs to Brady, who, 10 Super Bowls down, has already started plotting his offseason objective: He wants to get faster.

As he smiled the other day, Brady said he wanted to catch up with the younger generation of quarterbacks. Really, though, it is they who are trying to catch up with him, always and forever.