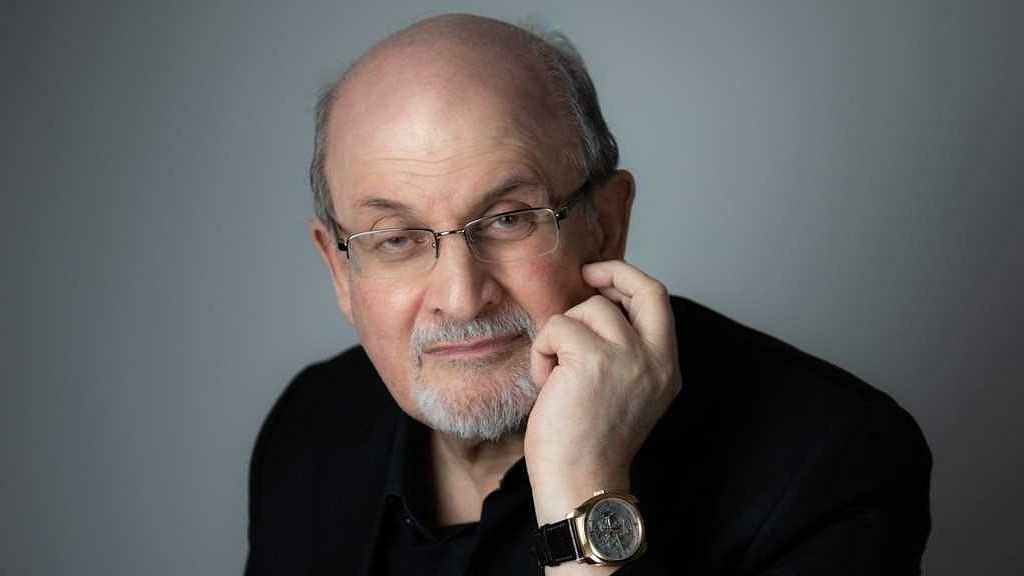

Although Salman Rushdie was forced to go into hiding for several years in the 1990s, he has been living freely in New York in recent years, his friends say, appearing in public without evident security, even as his status as a high-profile author and champion of free speech has made him a celebrity.

In an interview last year, Rushdie, 75, was casual and easygoing as he spoke about literature from his Manhattan home, adopting the air of someone who had long ago reentered society and reveled in being a man about town. Asked about the long-standing call for his death, he answered simply, “Oh, I have to live my life.”

That was a dramatic change from 1988, when his novel The Satanic Verses was published. Some Muslims considered it blasphemous because it fictionalised part of the life of the Prophet Mohammed, and the following year Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran, issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill Rushdie.

Rushdie lived in London for some 10 years after the fatwa was issued. In the first few months, his wife at the time, novelist Marianne Wiggins, said the couple had moved 56 times, once every three days. The couple soon separated, under strain from the tense life they lived.

After that, Rushdie remained largely under British police protection, at a fortified safe house with security gate and a porch with a double door. The house was equipped with bulletproof glass, security cameras, fortified walls, lodging for six police officers and “bombproof net curtains.”

Six years after the fatwa was issued, Rushdie began to appear in public again. In September 1995, he attended his first publicly scheduled appearance, at a London panel discussion called “Writers and the State.”

“The term ‘coming out’ has gone through some unusual metamorphoses,” a smiling and relaxed Rushdie said. “Thank you for attending this little coming-out party.”

At the time, Rushdie was never without heavily armed bodyguards. Still, as Sarah Lyall of The New York Times reported, “he travels, eats in restaurants, appears at bookstores and is a regular fixture at London’s smartest literary parties.”

In 2000, Rushdie appeared as a writer in a music video for U2 song The Ground Beneath Her Feet. In a scene at a book party in 2001 film Bridget Jones’s Diary Rushdie appeared as himself, playfully sending up his reputation as an intimidating intellectual.

More recently, he had a cameo in a 2017 episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm advising Larry David about how to handle the fatwa placed on him after David’s character, appearing on television to promote a musical he wrote based on Rushdie’s life, mocked the ayatollah on television.

Describing his decision to go on the show, Rushdie later said that “if we’d reached the point where we can make fun of it, then that feels good.”

Suzanne Nossel, CEO of free speech organisation PEN America, said that Rushdie had done many events with the organisation in recent years, without any special security arrangements by PEN.

“There was a feeling that the threat had lifted and he was able to focus on the threats facing others, standing up for others facing peril,” Nossel said.

Ayad Akhtar, a novelist, playwright and the current president of PEN America, is a friend of Rushdie’s. He never saw Rushdie bring along any kind of security detail to public events or venues, he said, nor had they ever discussed the threats he faced.

Rushdie’s early work questioned the founding myths of India and Pakistan and eventually Islam, Akhtar said, calling The Satanic Verses a seminal moment for his own development as a young Muslim writer.

“Playing that role as a writer,” Akhtar said, “as a questioning conscience for all of us who came from the subcontinent or were born into the faith, it was a singular act of creativity, courage and brilliance.”