The closed-door trial began in secret, with the two defendants appearing by video. The defence attorney wasn’t even aware of what was happening. By the time he rushed to the court on Tuesday afternoon, it was all over, in less than an hour.

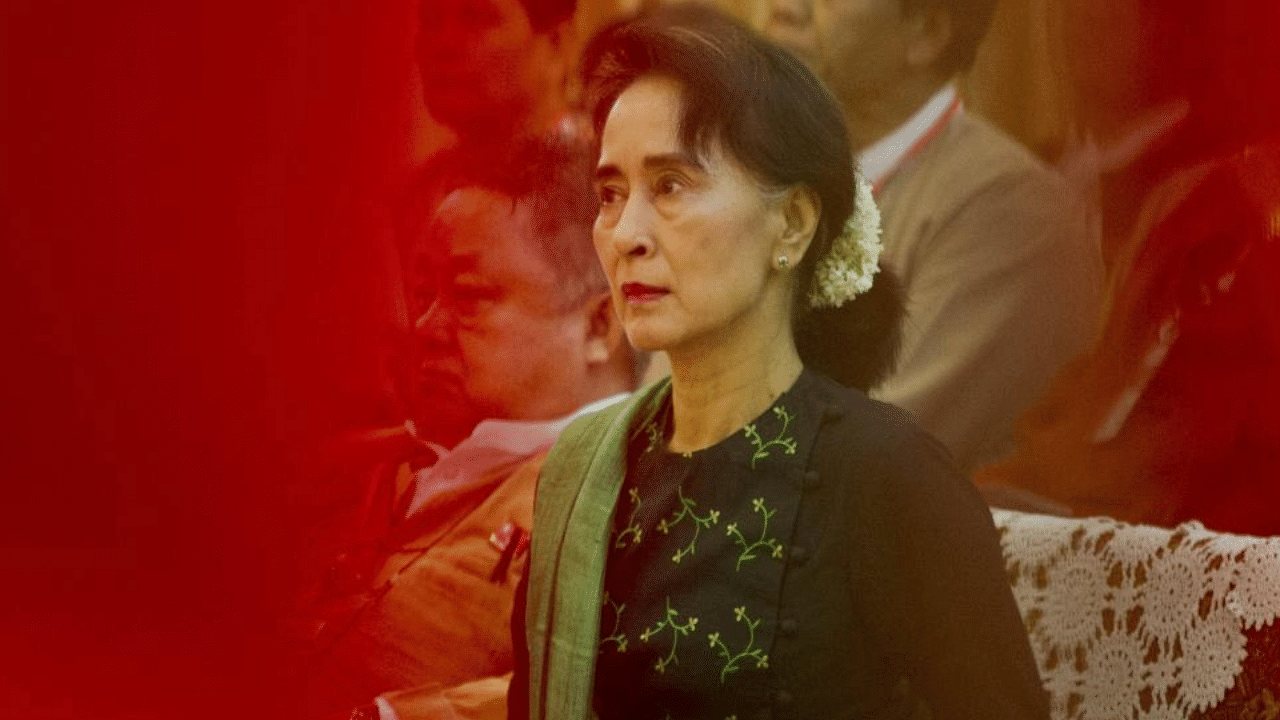

The trial of Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s civilian leader who was ousted in a military coup two weeks ago, and Win Myint, the deposed president, began on Tuesday. They face obscure charges that could land them in prison for six years and three years respectively.

Suu Kyi was accused of violating import restrictions after walkie-talkies and other foreign equipment were found in her villa compound. She was also charged with contravening a natural disaster management law by interacting with a crowd during the coronavirus pandemic, a charge that had not been disclosed publicly before.

Win Myint has been charged with breaching the natural disaster restrictions.

The first day of the trial of Myanmar’s elected leaders capped a dizzying two weeks in which the military, which ruled the country for nearly half a century before sharing some power with a civilian government, locked up hundreds of people, stripped away civil liberties for the entire population and steadfastly ignored the millions of protesters who have risen up against their seizure of power.

Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate who led Myanmar’s democratic opposition for decades, has not been seen publicly since soldiers descended on her villa in the early morning hours of Feb. 1, but her smiling face has been omnipresent on posters and signs carrying by protesters during their daily rallies.

The trial, as with so many legal cases in Myanmar, was filled with anomalies. Khin Maung Zaw, Suu Kyi’s lawyer, was originally told the court proceedings would begin on Monday. Then he was led to believe it would be Wednesday. At 11 a.m. Tuesday, he was suddenly notified that his client was appearing via video conference in a court in Naypyitaw, the capital.

“The timing seems like they don’t want public attention in this case,” said Khin Maung Zaw, a veteran human-rights lawyer.

But as word of the trial trickled out, people in Myanmar quickly organized an online campaign urging a million people to gather near Sule Pagoda in Yangon, the largest city, on Wednesday.

Khin Maung Zaw has been told that the next trial session will be on March 1 and that the trial could last for six months to a year.

Win Myint, who served as a High Court lawyer before he became president, will represent himself.

Khin Maung Zaw said that he had already begun building his client’s defense, if only he would be allowed to present her case in court. While Suu Kyi was charged with violating import regulations, the walkie-talkies in question were used by her security team, which was assigned to her by the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs, he said.

“That question is the first question I will ask the court when I have a chance,” Khin Maung Zaw said. “Let’s see how they will answer it.”

Shortly after the trial of Suu Kyi and Win Myint began on Tuesday, the nation’s new rulers, who call themselves the State Administration Council, held a news conference in which they defended their treatment of Myanmar’s elected leaders.

“Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the president are detained in safe places, and their condition is good,” said Brig. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, who appeared in civilian clothes at his first meeting with the news media.

Dozens of government leaders were detained alongside Suu Kyi and Win Myint, but the charges against them have not been made public. A rollback of fundamental rights in Myanmar, announced last weekend, allows for indefinite detention.

Zaw Min Tun slapped away questions about the possible effects of targeted financial sanctions from the West. He dismissed a civil disobedience movement that has united some 750,000 doctors, civil servants, railway workers, electricity providers and others as evidence of the protesters’ lack of patriotism.

And he defended the military’s repeated suspensions of telecommunications services and its bans on popular social media sites.

“We need some kind of restriction,” he said, “because Facebook is the main source of misinformation and fake news.”

As Zaw Min Tun’s words were broadcast live on Facebook, people in Myanmar began a humorous campaign to report the news conference as disinformation that breached Facebook’s social media policies.

It was over before any action might have been taken.