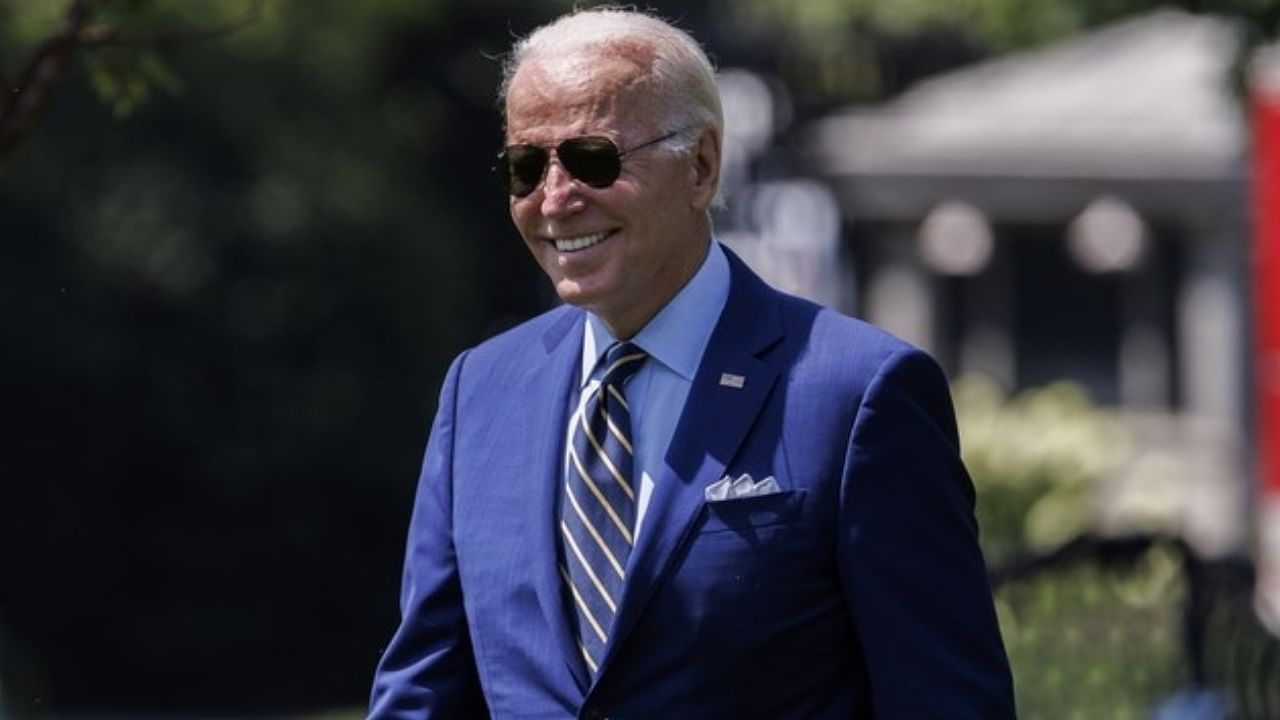

Soon after taking office, President Joe Biden went to State Department headquarters to tell the rest of the world that the United States could be counted on again after four years of Donald Trump's bull-in-the-china-shop foreign policy.

“America is back,” Biden said, in what has become a mantra.

But keeping his promises on the international stage has proved much more difficult than Biden might have expected. Domestic politics have routinely been a roadblock when it comes to taking action on climate change, taxes and pandemic relief, undermining hopes that Biden could swiftly restore the US to its unquestioned role as a global leader.

The result is an administration straining to maintain its credibility abroad while Biden fights a rearguard action on Capitol Hill. It's simply more difficult to press other countries to do more to address challenges that span borders when he's struggling to deliver on those same issues at home.

“Every new thing takes a little bit of the luster off, and contributes to a sense of a struggling president," said Michael O'Hanlon, the Brookings Institution director of research for foreign policy.

Biden has earned respect for marshaling an international response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the US has shipped more coronavirus vaccines around the world than any other country.

Adrienne Watson, a spokesperson for the National Security Council, said Biden “has restored our alliances, including our essential partnership with Europe, built new platforms and institutions in some of the most relevant regions of the world," including the Indo-Pacific, and shown leadership on "the issues that matter the most."

But his foreign policy record is much more mixed when he needs to secure support in Congress.

Although he has secured close to $54 billion in military and financial assistance for Ukraine — something Watson described as a historic amount delivered with “unprecedented speed” — Republicans remain uniformly opposed to many of his initiatives, and Biden has been hobbled because of disagreements among Democrats.

The latest problem has been the breakdown of on-and-off negotiations with Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., who pulled his support for a potential compromise on legislation to address climate change and create a global minimum tax.

On both issues, Biden had already made pledges or reached an international agreement, but the US commitment is now in doubt.

The global minimum tax is aimed at making it harder for companies to dodge taxes by moving from country to country in search of lower rates. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen played a leading role in negotiating the deal among 130 countries.

“Reaching this consensus wasn't easy," Biden said when the agreement was announced just over a year ago. "It took American vision, as well as a commitment to closely cooperate with our partners around the world. It's a testament to how leadership rooted in our values can deliver important progress for families everywhere.”

He acknowledged that “building on this agreement will also require us to take action here at home” — and now it looks like that action may not happen.

Biden wanted Congress to pass a proposal that would allow the US to impose extra taxes on companies that aren't paying at least 15%, either domestically or abroad.

But Manchin objected to tax changes in the legislation that's currently under consideration,

Administration officials said they are not giving up on a plan that they said would “level the playing field for US businesses, decrease incentives to move jobs offshore and close loopholes that corporations have used to shift profits overseas.”

"It's too important for our economic strength and competitiveness to not finalize this agreement, and we'll continue to look at every avenue possible to get it done," said Michael Kikukawa, a Treasury Department spokesman.

But pushing ahead with the original deal will likely prove difficult at this point, said Chye-Ching Huang, executive director of the Tax Law Center at the New York University School of Law.

"It's no doubt that this reduces the momentum,” she said.

She added: “There is a strong possibility that the major trading partners do this without the US but the path forward is rockier."

Manchin has also been an obstacle for Biden's climate change plans, a reflection of his outsize influence at a time when Democrats hold the narrowest of margins in the Senate.

A few months after taking office, Biden hosted a virtual conference with other world leaders, and he announced that he would increase the country's target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The decision was welcomed by scientists and politicians who worry that enough isn't being done to prevent the planet from warming to dangerous levels, and Biden has spoken of fighting climate change with “the power of our example.”

Biden's ability to meet his pledge, however, has been undermined twice recently. First the conservative majority on the Supreme Court limited the administration's powers to regulate emissions, and then Manchin said he wouldn't support new spending to support clean energy projects.

John Kerry, Biden's global climate envoy, said earlier this month that the administration's struggles could “slow the pace” of other countries' emissions cuts.

“They'll make their own analysis that will conceivably have an impact at what they decide to do or not," he said.

Biden is trying to demonstrate that he'll push forward on his own, without legislation, and he's considering declaring a state of emergency that would allow him to shift more resources toward climate initiatives.

But his powers are limited, and hitting the target may prove difficult, if not impossible.

Nathaniel Keohane, president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, said the clock is ticking until the next United Nations summit on climate change, which is scheduled for Egypt in November.

Unless the administration is able to demonstrate progress before then, “it will hamstring the US ability to continue to push more from other countries,” Keohane said. "It would deeply undermine US credibility on climate.”

He added, “More rhetoric is not going to satisfy the need at this point.”

Biden has also struggled to convince Congress to provide him with more funding to deal with the pandemic.

When Dr. Ashish Jha, who leads the administration's coronavirus task force, appeared in the White House briefing room for the first time in April, he emphasized that worldwide vaccinations were needed to prevent new variants from emerging.

“If we're going to fight a global pandemic, we have to have a global approach,” he said. “That means we need funding to ensure that we're getting shots in arms around the world.”

Biden originally wanted $22.5 billion. Lawmakers reduced the proposal to $15.6 billion, but even that was jettisoned from a $1.5 trillion government spending plan that the president signed in March.

Efforts to resuscitate the proposal have not been successful.

“The debacle over getting new money in the pipeline has really set us back," said J. Stephen Morrison, director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “There's paralysis and uncertainty."

Morrison emphasized that the United States has played “a very serious and honorable leadership role” with its donations of vaccines and its work with the World Bank to set up a new fund to prepare for future pandemics.

But without new legislation, Morrison said, more robust plans to support vaccination campaigns in other countries are on hold.

“We're in a difficult spot right now," he said.