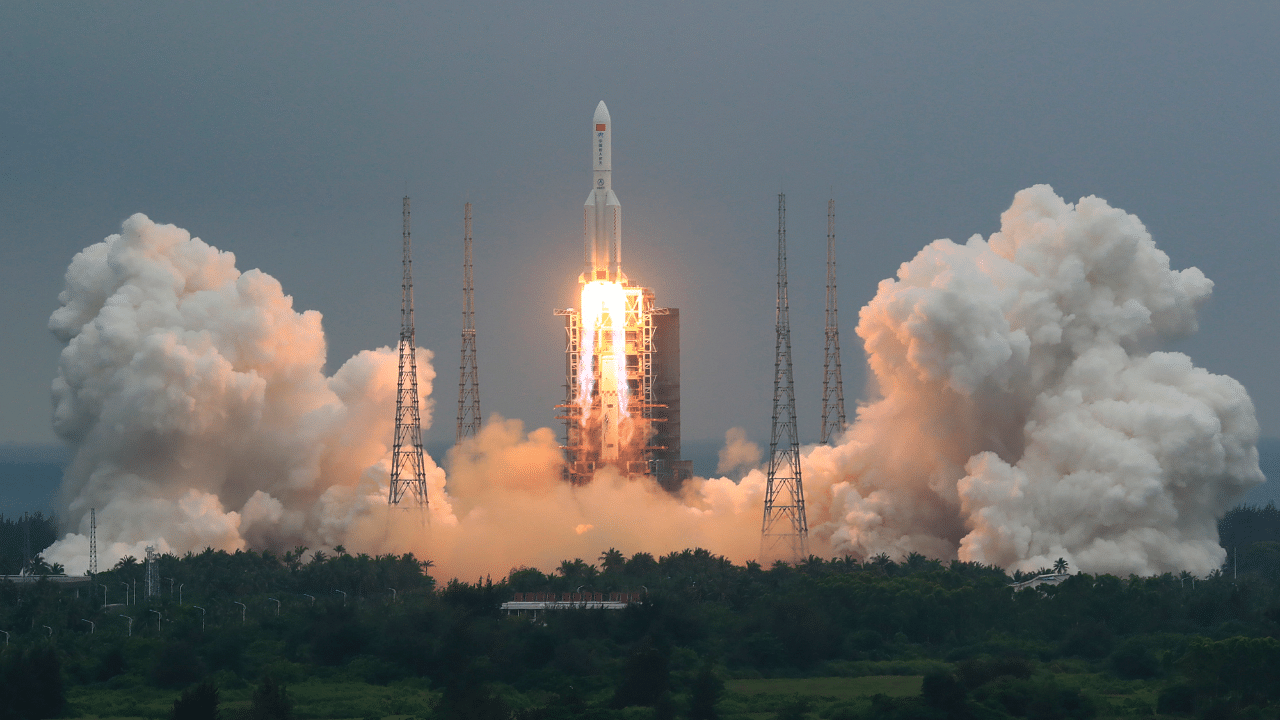

The launch of the first module of China's new space station - "Heavenly Palace" - on Thursday underlined how far the country has come in achieving its space dream.

The Tianhe core module houses life support equipment and a living space for astronauts, and is another key step in Beijing's grand plans to establish a permanent human presence in space.

Beijing has poured billions into its military-run space programme, with hopes of having a crewed space station by 2022 and eventually sending humans to the Moon.

The country has come a long way in its race to catch up with the United States and Russia, whose astronauts and cosmonauts have decades of experience in space exploration.

But Beijing sees its space project as a mark of its rising global stature and growing technological might.

Here is a look at China's space programme through the decades, and where it is headed:

Soon after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, Chairman Mao Zedong pronounced: "We too will make satellites."

It took more than a decade, but in 1970, China launched its first satellite on a Long March rocket.

Human spaceflight took decades longer, with Yang Liwei becoming the first Chinese "taikonaut" in 2003.

As the launch approached, concerns over the viability of the mission caused Beijing to cancel a live television broadcast at the last minute.

But it went smoothly, with Yang orbiting the Earth 14 times during a 21-hour flight aboard the Shenzhou 5.

China has launched five crewed missions since.

Following in the footsteps of the United States and Russia, China is striving to build a space station circling the planet.

The Tiangong-1 lab was launched in September 2011.

In 2013, the second Chinese woman in space, Wang Yaping, gave a video class from inside the space module to children across the world's most populous country.

The craft was also used for medical experiments and, most importantly, tests intended to prepare for the construction of a space station.

That was followed by the "Jade Rabbit" lunar rover in 2013, which first appeared a dud when it turned dormant and stopped sending signals back to Earth.

It made a dramatic recovery, however, ultimately surveying the Moon's surface for 31 months -- well beyond its expected lifespan.

In 2016, China launched its second orbital lab, the Tiangong-2. Taikonauts who have visited the station have run experiments on growing rice and other plants.

Under President Xi Jinping, plans for China's "space dream", as he calls it, have been put into overdrive.

China is looking to finally catch up with the US and Russia after years of belatedly matching their milestones.

In addition to a space station, China is also planning to build a base on the Moon, and the country's National Space Administration has said it aims to launch a crewed lunar mission by 2029.

But lunar work was dealt a setback in 2017 when the Long March-5 Y2, a powerful heavy-lift rocket, failed to launch on a mission to send communication satellites into orbit.

That forced the postponement of the launch of Chang'e-5, which was originally scheduled to collect Moon samples in the second half of 2017.

Another robot, the Chang'e-4, landed on the far side of the Moon in January 2019 -- a historic first.

This was followed by one which landed on the near side of the Moon late last year and raised a Chinese flag on the Moon's surface.

The unmanned Chinese spacecraft returned to earth in December with rocks and soil from the Moon -- the first lunar samples collected in four decades.

And the first images of Mars were sent back by the five-tonne Tianwen-1 in February, days before it entered the Red Planet's orbit.

It includes a Mars orbiter, a lander and a rover that will study the planet's soil.

China hopes to ultimately land the rover in May in Utopia, a massive impact basin on Mars.

The Chinese space station named Tiangong -- meaning "heavenly palace" -- will need around 10 missions to bring up more parts and assemble them into orbit.

Once completed, it is expected to remain in low Earth orbit at between 400 and 450 kilometres above our planet for 15 years.

It would realise an ambition to keep a long-term human presence in space.

While China does not plan to use its space station for international cooperation on the scale of the ISS, Beijing has said it is open to foreign collaboration.

But it is not yet clear how extensive that cooperation will be in a project of national prestige and security.

As the rocket carrying the first module tore through the sky, state media was in triumphant mood.

"A palace in the sky will no longer be just a romantic fantasy of the ancients," the TV anchor said.