The clandestine clinic was under fire, and the medics inside were in tears.

Hidden away in a Myanmar monastery, this safe haven had sprung up for those injured while protesting the military's overthrow of the government. But now security forces had discovered its location.

A bullet struck a young man in the throat as he defended the door, and the medical staff tried frantically to stop the hemorrhaging. The floor was slick with blood.

In Myanmar, the military has declared war on health care — and on doctors themselves, who were early and fierce opponents of the takeover in February. Security forces are arresting, attacking and killing medical workers, dubbing them enemies of the state. With medics driven underground amid a global pandemic, the country's already fragile healthcare system is crumbling.

“The junta is purposely targeting the whole healthcare system as a weapon of war,” says one Yangon doctor on the run for months, whose colleagues at an underground clinic were arrested during a raid. “We believe that treating patients, doing our humanitarian job, is a moral job….I didn't think that it would be accused as a crime.”

Inside the clinic that day, the young man shot in the throat was fading. His sister wailed. A minute later, he was dead.

One of the clinic's medical students, whose name like those of several other medics has been withheld to protect her from retaliation, began to sweat and cry. She had never seen anyone shot.

Now she too was at risk. Two protesters smashed the glass out of a window so the medics could escape. “We are so sorry,” the nurses told their patients.

One doctor stayed behind to finish suturing the patients' wounds. The others jumped through the window and hid in a nearby apartment complex for hours. Some were so terrified that they never returned home.

“I cry every day from that day,” the medical student says. “I cannot sleep. I cannot eat well.”

“That was a terrible day.”

The suffering caused by the military's takeover of this nation of 54 million has been relentless. Security forces have killed at least 890 people, including a 6-year-old girl they shot in the stomach, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, which monitors arrests and deaths in Myanmar. Around 5,100 people are in detention and thousands have been forcibly disappeared. The military, known as the Tatmadaw, and police have returned mutilated corpses to families as tools of terror.

Amid all the atrocities, the military's attacks on medics, one of the most revered professions in Myanmar, have sparked particular outrage. Myanmar is now one of the most dangerous places on earth for healthcare workers, with 240 attacks this year -- nearly half of the 508 globally tracked by the World Health Organization. That's by far the highest of any country.

“This is a group of folks who are standing up for what's right and standing up against decades of human rights abuses in Myanmar,” says Raha Wala, advocacy director of the U.S.-based Physicians for Human Rights. “The Tatmadaw is hell-bent on using any means necessary to quash their fundamental rights and freedoms.”

The military has issued arrest warrants for 400 doctors and 180 nurses, with photos of their faces plastered all over state media like “Wanted” posters. They are charged with supporting and taking part in the “civil disobedience” movement.

At least 157 healthcare workers have been arrested, 32 wounded and 12 killed since Feb. 1, according to Insecurity Insight, which analyzes conflicts around the globe. In recent weeks, arrest warrants have increasingly been issued for nurses.

Myanmar's medics and their advocates argue that these assaults violate international law, which makes it illegal to attack health workers and patients or deny them care based on their political affiliations. In 2016, after similar attacks in Syria, the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding that medics be granted safe passage by all parties in a war.

“In other country's protests, the medics are safe. They are exempt. Here, there are no exemptions,” says Dr. Nay Lin Tun, a general practitioner who has been on the run since February, and now provides care covertly.

Medics are targeted by the military because they are not only highly respected but also well-organised, with a strong network of unions and professional groups. In 2015, doctors pinned black ribbons to their uniforms to protest the appointment of military personnel to the Ministry of Health. Their Facebook page quickly gained thousands of followers, and the military appointments stopped.

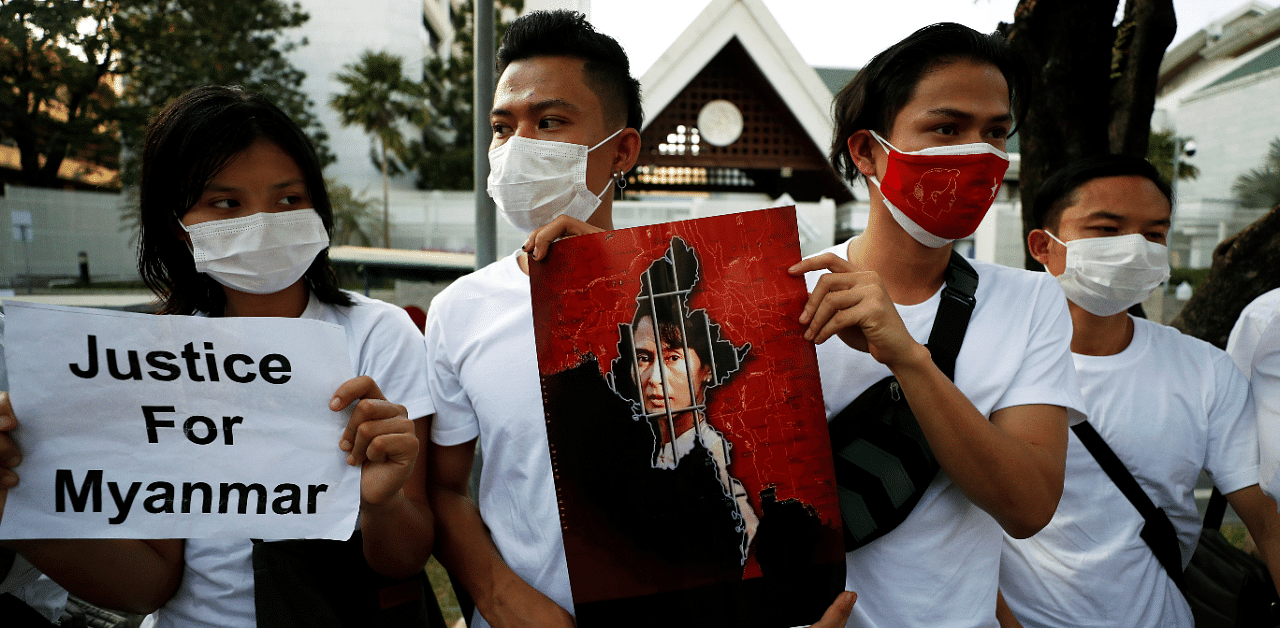

This time, the protest by medics started days after the military ousted democratically elected leaders, including Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, from power. From remote towns in the northern mountains to the main city of Yangon, they walked off their jobs on military-owned facilities, pinning red ribbons to their clothes.

The response from the military was fierce, with security forces beating medical workers and stealing supplies. Security forces have occupied at least 51 hospitals since the takeover, according to Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights and the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights.

On March 28, during a strike in the city of Monywa, a nurse was fatally shot in the head, according to AAPP. On May 8, hundreds of miles away in northern Kachin state, a doctor was arrested, tied up and also fatally shot in the head while passing a military base.