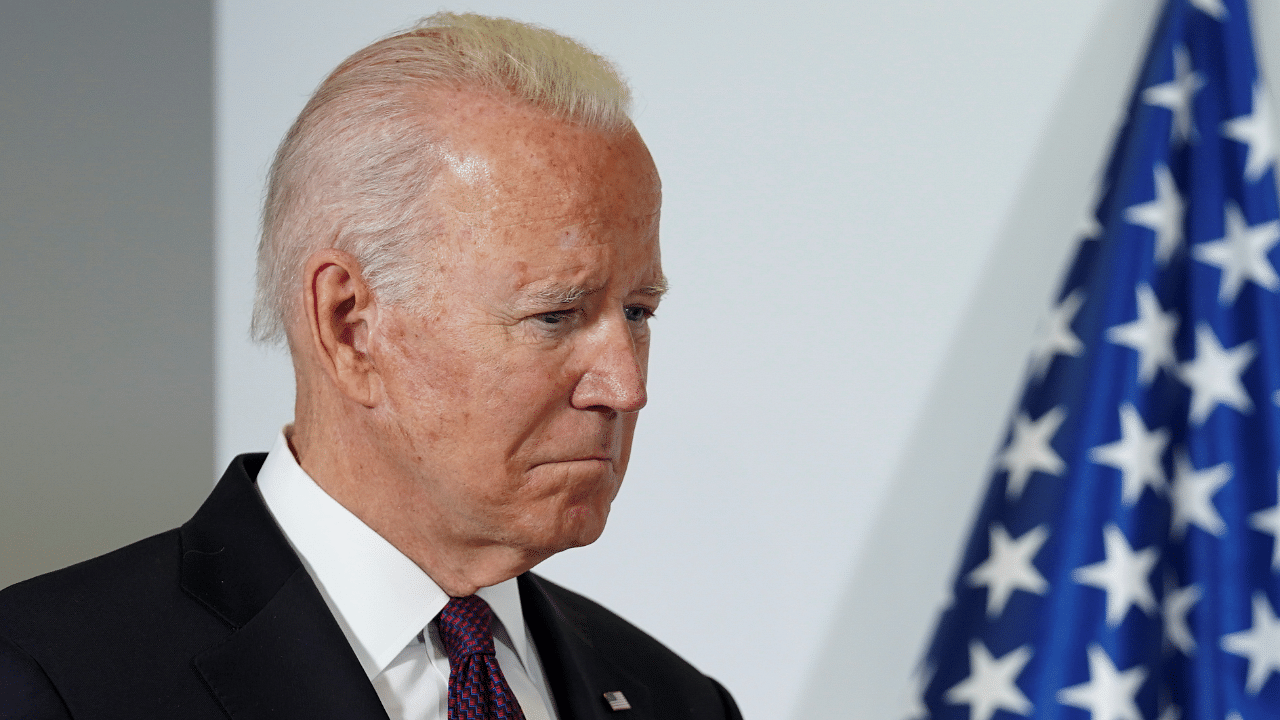

When President Joe Biden held a video call with European leaders about Ukraine this week, it had all the urgency of a Cold War-era crisis, replete with the specter of Russian tanks and troops menacing Eastern Europe. But Biden expanded the seats on his war council, adding Poland, Italy and the European Union to the familiar lineup of Britain, France and Germany.

The effort to be inclusive was no accident: After complaints from Europeans that they were blindsided by the swift US withdrawal from Afghanistan last summer, and that France was frozen out of a new defense alliance with Australia, Biden has gone out of his way to involve allies in every step of this crisis.

For the Biden administration, it amounts to a much-needed diplomatic reset. The United States, European officials say, has acted with energy and some dexterity in orchestrating the response to Russia’s threatening moves. Since mid-November, it has conducted at least 180 senior-level meetings or other contacts with European officials. Some marvel at having their American counterparts on speed dial.

Despite being dragged down at home by domestic problems and viewed as a transitional figure in some skeptical European capitals, Biden has emerged as the leader of the West’s effort to confront the threats from Russian President Vladimir Putin. The administration’s emphasis on unity, American officials say, is largely intended to frustrate Putin’s desire to use the crisis to fracture NATO.

Before delivering a written response to Putin’s security demands on Ukraine on Wednesday, the administration traded multiple drafts of the document with the Europeans, insisting that every paragraph that affected individual countries be reviewed, word for word, by their leaders, according to American officials.

“The concern here was ‘No surprises,’” said an official who was involved.

The Russians, who want the West to pledge that Ukraine will never join NATO, gave a cool reception to the US responses Thursday, saying there was “not much cause for optimism,” and leaving unclear what their next step might be.

In a phone call Thursday, Biden told Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy that the United States and its allies would “respond decisively if Russia further invades Ukraine,” according to a White House statement, and that the United States was considering ways to help Ukraine’s economy.

The United States also called for the United Nations Security Council to hold an open meeting on Monday to discuss “Russia’s threatening behavior against Ukraine.”

“This is not a moment to wait and see,” Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield said in a statement Thursday.

The United States is not relying on diplomacy alone. It has put 8,500 troops on alert to be deployed to Eastern Europe, sent defensive weapons to Ukraine and is negotiating to divert natural gas from other suppliers if Russia cuts off pipelines that supply Germany and other countries.

“We had a low point in terms of trust and mutual respect last summer because of the Afghanistan breakdown,” said Wolfgang Ischinger, a former German ambassador to Washington. Now, he said, “no one can complain that there isn’t a renewed sense of American leadership.”

Biden’s handling of the crisis has not been without missteps: His recent statement that a “minor incursion” by Russia would provoke a different response from the West than an invasion angered Ukraine and alarmed European governments, especially those bordering Russia. It necessitated a hurried cleanup operation by the White House.

Europeans worry about Biden’s staying power, the potential return of former President Donald Trump and the resolve of the United States, for which Ukraine is not an on-the-doorstep crisis as it is for Europe. Some believe Putin is exploiting the same perceived vulnerabilities on both sides of the ocean.

“He senses weakness in Biden and a certain amount of political churn in Europe,” said Ian Bond, a former British diplomat who is now head of foreign policy at the Center for European Reform, a London research group. “Germany has a new government finding its feet, French elections, U.K. not in great shape, Europe emerging from pandemic. I think he does see Biden as a quite weak transitional figure.”

Indeed, Putin is driving events more than Biden. His aggressive tactics are forcing Europe and the United States together. And he has shown little interest in striking a deal on Ukraine with anyone other than the president of the “other superpower.”

That testifies to the central role of the United States in guaranteeing the security of Europe.

It also means that whatever the doubts about Biden in Moscow or European capitals, he will be the fulcrum of the West’s response. Europeans say he has embraced that role with more enthusiasm than either Trump or his former boss, President Barack Obama.

Trump withheld military aid to Ukraine and pressured its president to investigate Biden, then looming as his political rival. Obama did not view Ukraine as a core strategic interest of the United States even after the annexation of Crimea, prompting France and Germany to create a group that has met periodically with Russia and Ukraine since 2014 to discuss how to curb hostilities.

“When the Ukrainian crisis erupted in 2014, the American policy was ‘Try not to get involved,’” said Gérard Araud, a former French ambassador to Washington. “They outsourced the handling of it to France and Germany.”

The White House’s efforts in part reflect the bitter lesson of the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, when Europeans criticized the United States for failing to consult them, a charge the White House disputes.

Ischinger, who now chairs the Munich Security Conference, recalled an American official telling him at that time that the era had passed in which the United States viewed itself as a “European power,” one whose active involvement was critical to the continent’s strategic balance.

“What we have witnessed over the last couple of weeks demonstrates this was an incorrect assessment,” he said.

This time, American officials have consulted with a galaxy of groups encompassing the political and security bureaucracy of the European continent: the EU, the European Commission, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the Bucharest Nine, a group of eastern NATO members.

“They learned a real lesson from Afghanistan,” said Ivo Daalder, a former American ambassador to NATO. “They have been extraordinarily effective, in a way we haven’t seen for a long time, in engaging with allies.”

One challenge for Biden, experts say, is the lack of a European leader to help pull the rest of the continent into line. That was the role former German Chancellor Angela Merkel played for Obama and President George W. Bush. It was the role former British Prime Minister Tony Blair played for Bush, with little success on Iraq, and for President Bill Clinton, with more success on Kosovo.

Britain’s current prime minister, Boris Johnson, is preoccupied by a scandal over parties at Downing Street during the pandemic. In any event, Britain’s departure from the EU has deprived it of its traditional role as a bridge between Washington and Brussels, although it remains a central player in NATO.

Britain has tried to stake out a forceful role, shipping anti-tank weapons to Ukraine and drafting legislation that will allow it to impose sanctions on Russia if it launches an invasion. But it is driven more by a post-Brexit desire to act independently than to serve as a wingman for Washington.

France has also hardened its position, with President Emmanuel Macron offering to send troops to Romania to reinforce NATO’s eastern flank. But Macron faces an election in April, and he, too, has asserted a more independent role for Europe in engaging with Russia. On Friday, he and Putin will speak by phone.

French diplomats said Macron’s efforts should not be viewed as an obstacle to the United States because he has pledged to take any common European position to NATO, where it would be thrashed out with the Americans.

“Macron’s problem is Germany,” Araud said.

The new coalition government in Germany is being pulled in different directions, with the Greens and the Free Democrats more inclined to take a hard line against Moscow, while the Social Democrats are traditionally eager to preserve trade and diplomatic ties. Chancellor Olaf Scholz, a Social Democrat, has been a diffident figure so far.

“You don’t have reassuring Merkel, who can calm things down and keep everything pulling in the same direction,” said Jonathan Powell, who served as chief of staff to Blair.

Despite all the potential for disunity, diplomats point out that Europe, NATO and the United States agree on two fundamental issues. No one plans to send combat troops into Ukraine. All agree on the importance of imposing sanctions on Russia, though the Europeans, particularly the Germans, may balk at the most draconian measures because of the collateral damage to their economies.

European officials insist that Germany is willing to pay a significant price and that nothing is off the table, including the Nord Stream 2 pipeline that would send gas from Russia to Western Europe — and give Putin valuable leverage.

Putin’s string of provocations — moving large numbers of troops into Belarus, and holding large military exercises on Ukraine’s borders, naval exercises in the Baltic Sea and even a planned exercise off the coast of Ireland — have drawn Europeans and Americans together in a way that no European or American leader could.

“Putin is so extreme in his demands and threats that it’s impossible not to close ranks with other countries,” Araud said. “You don’t have an alliance without a threat, and Putin is a threat.”

Check out DH's latest videos