In the basement of the bookshop she manages in western Ukraine, Romana Yaremyn shows hundreds of books stacked halfway to the ceiling after they were evacuated from the country's war-torn east.

Packed together in white parcels, the titles rescued from Kharkiv fill up what was once the children's reading room.

They are just a fraction of those at the shop's publishing house in the eastern city under Russian fire, she said.

"Our warehouse workers tried to at least evacuate some of the books. They loaded up a truck and all this was delivered through a postal company," said the 27-year-old, dressed in a yellow hoodie.

They started with these, their most recent and most popular publications, many of which are children's books.

The western city of Lviv has remained relatively sheltered from war since Russia invaded two months ago, with the exception of deadly airstrikes near the railway last week.

Hundreds of thousands of people, mainly women and children, have fled to or through the country's cultural capital since the fighting erupted.

"I don't know how my colleagues in Kharkiv have stayed there," Yaremyn said.

"Those who fled and stayed with me said they felt that they wanted to level the city to the ground."

Yaremyn said the bookshop swiftly reopened a day after the invasion, providing shelter in the basement when the air raid sirens went off, and holding reading sessions there with displaced children.

During the first wave of arrivals, parents who had left home with next to nothing flooded in seeking fairy tales to keep their children distracted in the bunkers.

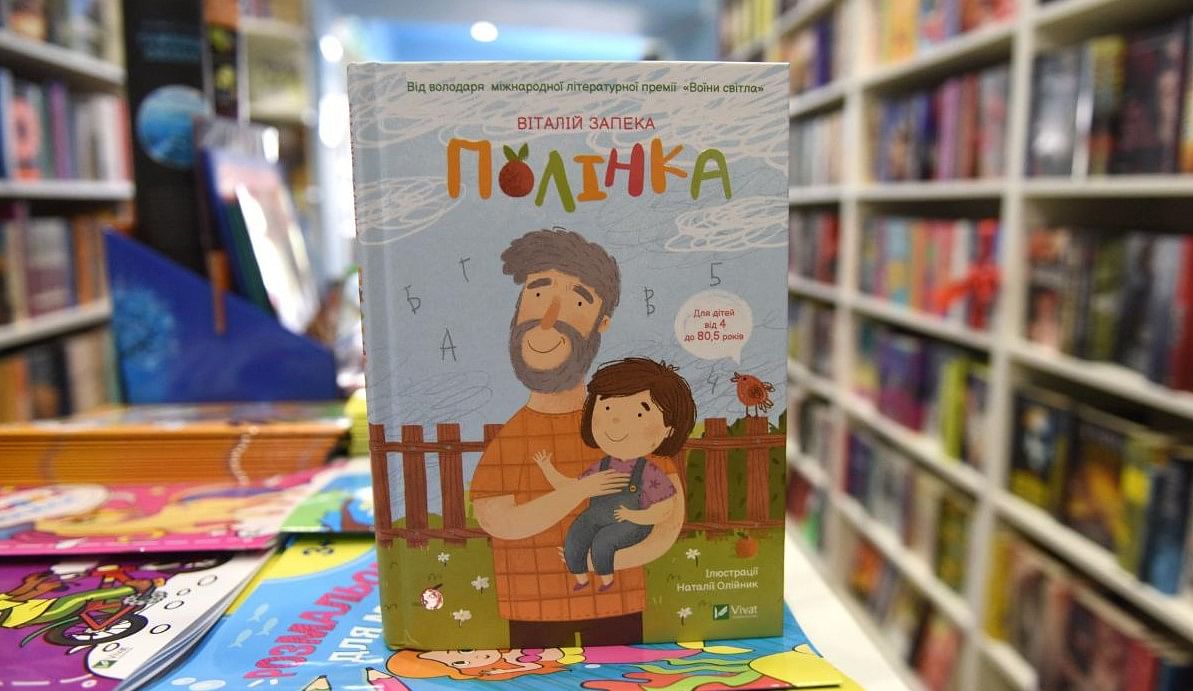

A few parents bought "Polinka", the story of a girl and her grandfather, published just before the invasion and written by a man who is now on the front.

"He wanted to leave something behind for his grandchild," she said.

From the shelves in the adult section, Yaremyn pulled out a collection of essays on Ukrainian women forgotten by history. Its writer too is now fighting the Russians, she said.

"A lot of our authors are in the army now," she said.

As sirens wail across Lviv to signal the end of a morning air raid alarm, baristas return to their coffee shops to fire up their espresso machines until the next warning.

The sun pours down from a blue sky, and a young man and woman press their heads together seated on a terrasse. The city's numerous bookshops are open for business.

In a pedestrian tunnel under a road in the city centre, several tiny stalls sell translations of foreign classics like George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four" or even manga titles.

Near the Royal Arsenal museum, a pigeon sits on the head of a tall muscular statue of Ivan Fyodorov, a 16th-century printer from Moscow buried in Lviv.

At his feet, when it does not rain and there are no sirens, a few second-hand booksellers wait for customers.

Dressed in a light blue coat and woolly hat, Iryna, 48, sat near rows of literature and history books for sale or rent. Rentals for a small fee used to be popular with the older generation, she said.

Iryna, who did not give her second name, said she stopped working for more than a month after the war broke out.

When she returned to the cobbled square in early April, many parents from the east came looking for books for their children. "I gave them a lot because kids want to read," she said.