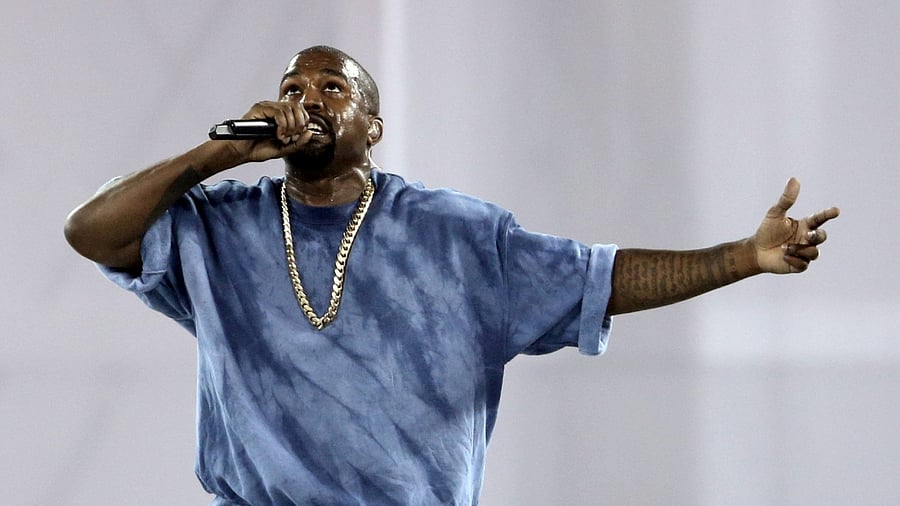

Kanye West.

Credit: Reuters Photo

The Adidas team was huddled with Kanye West, pitching ideas for the first shoe they would create together. It was 2013, and the rapper and the sportswear brand had just agreed to become partners. The Adidas employees, thrilled to get started, had arrayed sneakers and fabric swatches on a long table near a mood board pinned with images.

But nothing they showed that day at the company’s German headquarters captured the vision West had shared. To convey how offensive he considered the designs, he grabbed a sketch of a shoe and took a marker to the toe, according to two participants. Then he drew a swastika.

It was shocking, especially to the Germans in the group. Most displays of the symbol are banned in their country. The image was acutely sensitive for a company whose founder belonged to the Nazi Party. And they were meeting just miles from Nuremberg, where leaders of the Third Reich were tried for crimes against humanity.

That encounter was a sign of what was to come during a collaboration that would break the boundaries of celebrity endorsement deals. Sales of the shoes, Yeezys, would surpass $1 billion a year, lifting Adidas’ bottom line and recapturing its cool. West, who now goes by Ye, would become a billionaire.

When the company ended the relationship last October, it appeared to be the culmination of weeks of West’s inflammatory public remarks — targeting Jews and disparaging Black Lives Matter — and outside pressure on the brand to cut ties. But it was also the culmination of a decade of Adidas’ tolerance behind the scenes.

Inside their partnership, the artist made antisemitic and sexually offensive comments, displayed erratic behavior and issued ever-escalating demands, a New York Times examination found. Adidas’ leaders, eager for the profits, time and again abided his misconduct.

While some other brands have been quick to end deals over offensive or embarrassing behavior, Adidas held on for years.

This article is the fullest accounting yet of their relationship. The Times interviewed current and former employees of Adidas and of West and obtained hundreds of previously undisclosed internal records — contracts, text messages, memos and financial documents — that reveal episodes throughout a partnership that was fraught from the start.

Just weeks before the 2013 swastika incident, the Times found, West made Adidas executives watch pornography during a meeting at his Manhattan apartment, ostensibly to spark creativity. In February 2015, preparing to show the first Yeezy collection at New York Fashion Week, staff members complained that he had upset them with angry, sexually crude comments.

He later advised a Jewish Adidas manager to kiss a picture of Adolf Hitler every day, and he told a member of the company’s executive board that he had paid a seven-figure settlement to one of his own senior employees who accused him of repeatedly praising the architect of the Holocaust.

Again and again, West contended that Adidas was exploiting him. “I feel super disrespected in this ‘partnership,’” he said in one text message. He routinely sought more money and power, even suggesting that he should become Adidas’ CEO.

His complaints were often delivered amid mood swings, creating whiplash for the Adidas team working with him. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, he at times rejected the assessment and resisted treatment.

As Adidas grew more reliant on Yeezy sales, so did West. In addition to royalties and upfront cash, the company eventually agreed to another enticement: $100 million annually, officially for Yeezy marketing but, in practice, a fund that he could spend with little oversight.

In a statement to the Times, Adidas said it “has no tolerance for hate speech and offensive behavior, which is why the company terminated the Adidas Yeezy partnership.” The brand turned down interview requests and, citing confidentiality rules, declined to comment on financial aspects of the collaboration and Adidas’ relationship with West.

West declined interview requests and did not respond to written questions or provide comments.

After the relationship ruptured and Yeezy sales came to a halt, both Adidas and the musician were hit hard. The company projected its first annual loss in decades. West’s net worth plummeted.

But they had at least one more chance to keep making money together.

The company announced in May that it would begin releasing the remaining $1.3 billion worth of Yeezys from warehouses around the world.

The Yeezy debut at New York Fashion Week in 2015 was a display of star power. The front row was packed with Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Rihanna and a cluster of Kardashians. The event streamed in movie theaters around the world.

It was exactly what West — and Adidas — had wanted.

The company’s roots stretch back nearly a century, when Adi Dassler began making athletic shoes in the laundry room of his family’s Bavarian home. Like many business owners of his era, Dassler joined the Nazi Party. After World War II, he founded Adidas, which went on to capture much of the soccer-based market in Europe and made inroads in America as hip-hop stars helped popularize the brand.

But everything changed after Nike signed an endorsement deal in 1984 with an up-and-coming basketball player named Michael Jordan. That partnership would help turn sneakers into cultural currency around the world. And Nike, making billions of dollars a year from Air Jordans, became No. 1.

By 2013, Adidas had just 8 per cent of the US athletic footwear market, compared with Nike’s nearly 50 per cent, according to industry data, and it was losing hope of catching up.

West was also feeling stalled.

Raised in Chicago by his mother, an English professor, he achieved early success producing music for Jay-Z and other artists before becoming a rap star. His 2004 debut album, “The College Dropout,” was considered game changing for hip-hop, for its cutting-edge production and for West’s middle-class viewpoint and preppy-meets-street style. But West had struggled to break into fashion, despite his burning ambition to design.

In a phone call in the summer of 2013, West told Jon Wexler, then Adidas’ global director of entertainment and influencer marketing, that he was determined to become a partner in designing shoes.

Adidas took a big swing, offering the rapper a contract through 2017 with the most generous terms it had ever extended to a nonathlete. It went far beyond typical celebrity licensing deals. West, then 36, would become a co-creator of shoe and clothing lines, collecting a 15 per cent royalty on net sales with at least $3 million a year guaranteed.

Adidas employees quickly discovered that West was brimming with ideas. They also learned that he operated unlike anyone else they had encountered.

He could be enthusiastic to the point of creating chaos. Early on, he showed up unexpectedly at Adidas’ New York office with his fiancee, Kim Kardashian, the queen of reality television and soon social media too, and tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of sewing machines. It was so disruptive that he was sent to a studio across town. Once immersed in the design work, he so obsessed over every detail that it was hard to finish anything.

And he was quick to anger when frustrated. Running up against the deadline for the first Yeezy fashion show in February 2015, he lashed out, using sexually explicit language, at Rachel Muscat — the rare female manager in a male-dominated industry — and other Adidas employees. Some complained about the verbal abuse to Adidas higher-ups, according to several members of the team, who spoke only on the condition of anonymity because they are bound by nondisclosure agreements.

Attention quickly shifted to the show, however, where the shoes drew raves. Released in limited runs over the next few months, the shoes sold out in hours, crashing servers and sending prices soaring on resale sites.

First came a suede high-top, followed by the Yeezy Boost 350. The 350 won top honors that year at the industry’s annual awards ceremony, considered the “shoe Oscars.”

A Morals Clause

Eager to build on their success, Adidas and West were hammering out a new contract in 2016.

The company wanted to entice West into a long-term commitment. But it also wanted to better protect itself. Executives were insisting on a clause that would allow Adidas to end the deal over a range of behaviors that could threaten its reputation.

Representing West was Scooter Braun, a bulldog of a manager best known then for catapulting Justin Bieber to fame. During negotiations, Braun argued that only a criminal offense, like shooting someone, would be adequate cause for Adidas to walk away from his client.

But the terms Adidas wanted were standard.

West continued to show pornography to Adidas employees. They also said they had seen him drinking at work.

In interviews years later, West would reveal addictions to alcohol and pornography. He had already acknowledged his deep depression after his mother’s unexpected death in 2007.

During negotiations on the morals clause, an Adidas lawyer, along with Wexler and Jim Anfuso, the brand’s general manager for Yeezy, refused to back down. Their position was that Adidas’ new CEO, Kasper Rorsted had to have clear-cut conditions for pulling the plug on the Yeezy deal.

West eventually conceded on Adidas’ terms for termination: felony conviction; bankruptcy; 30 consecutive days of mental health or substance abuse treatment; or anything that brings “disrepute, contempt, scandal” to him or tarnishes Adidas, according to a copy of the contract obtained by the Times.

The agreement was also loaded with financial incentives. The value of the deal would come to surpass that of his music assets, according to a Forbes assessment of his net worth.

During the negotiations, Adidas projected that net sales of Yeezys would grow from $65 million in 2016 to $1 billion by 2021; West would continue to get a 15 per cent royalty, now with at least $10 million a year guaranteed.

The brand was gaining ground in the United States; it would reach more than 11% of the market by the next spring. Adidas was offering West $15 million upfront, along with millions of dollars in company stock each year. The company also intended to dedicate 20 employees to a Yeezy unit at its U.S. headquarters in Portland, Oregon, up from just a handful. And while most celebrity branding agreements were short-term, this could extend for up to a decade if it met financial targets.

West signed the new contract in May 2016.

That fall, during his first tour in three years, his concerts took a turn.

He stunned a crowd in Sacramento, California, with a 17-minute tirade, praising President-elect Donald Trump; condemning the media, tech and music industries; bad-mouthing Beyoncé; and insinuating that Jay-Z might send “killers” after him. He cut the show short and, soon after, canceled his remaining performances.

Harley Pasternak, his friend and former trainer, arrived at the musician’s house in Los Angeles that week to find him consumed with paranoid thoughts, including that government agents were out to get him. He was writing Bible verses and drawing spaceships on bedsheets with a Sharpie while a handful of worried friends and employees lingered nearby. When Pasternak encouraged him to come to a nearby office he owned, West emerged with suitcases packed with pots, pans and Tupperware.

Pasternak, who later provided an account of the incident in a deposition for West’s touring company as it sought insurance payouts for the canceled shows, took him to the office. A psychiatrist from UCLA Medical Center and another doctor were among those called to the scene. After observing West’s behavior escalate — at one point, he threw a bottle, breaking a window — the doctor called 911.

“I think he’s definitely going to need to be hospitalized,” he told the operator on a recorded call.

After more than a week in the hospital in 2016, West began taking medication to treat bipolar disorder and kept a low public profile. But by the spring of 2018, he was off the meds, insisting that they dulled his creativity. While over the years, he has talked publicly about having bipolar disorder, he has at other times claimed that he was misdiagnosed.

That May, he set off an uproar, saying in a TMZ interview that 400 years of slavery “sounds like a choice” by generations of Black people.

Wexler told colleagues he was urging West to apologize. But Rorsted, Adidas’ CEO, batted the comment away. After pushing for the morals clause in West’s contract, it is not clear whether Adidas even considered invoking it.

The CEO’s response disturbed some Adidas employees, including in the Yeezy unit. Soon after the TMZ interview, those employees expressed their concerns to Eric Liedtke, Adidas’ global brand manager and an executive board member. In an overwhelmingly white company, Yeezy was the rare racially diverse unit that reflected the customer base. The team wanted to know: Did Adidas support West’s comments about slavery? Were the company’s European leaders blind to American race issues?

Liedtke promised that Adidas would work to address its racial diversity issues. But the company did not waver in its support of West — not then, and not as he expressed a troubling fixation on Jews and Hitler.

In 2018, West moved his Yeezy operation to Chicago, promising to create jobs there. When Rorsted and Liedtke visited that October, he raised new demands, including a seat on the company’s supervisory board, the role of Adidas creative director and maybe even CEO.

A week later, Rorsted and Liedtke described some of the proposals to Adidas’ executive board. They focused on two of West’s suggestions: spinning off Yeezy into a separate company or buying him out of his contract. The board also considered a third option: keeping the partnership as planned, according to company documents.

Anfuso, general manager of the Yeezy unit, told the executives that he favored paying West to make a clean break. He feared Adidas was becoming dangerously dependent on an increasingly unmanageable partnership, he told other colleagues.

In the end, the board decided Adidas would continue pursuing projects to help reduce its reliance on Yeezys. But it was not prepared to alter the partnership.

It is not clear if misgivings about the alliance ever reached the ultimate decision-makers: Adidas’ supervisory board. A company spokesperson declined to answer questions about that board’s proceedings. But its publicly released annual reports reflect no discussion of problems in the Yeezy partnership until 2022.

Rorsted, the CEO until late last year; his successor; and the chair of the supervisory board declined to be interviewed or to comment for this article, as did several other current and former executives in leadership roles, including Liedtke.

In 2019, West abruptly moved his Yeezy operation again, this time to remote Cody, Wyoming, and demanded that the Adidas team relocate. West, who had started describing himself as a born-again Christian, used “terms like ‘believer’ and ‘pilgrimage’” to describe those who would follow him to Cody.

West had already listed more requirements: a $1 billion advance, a 15% profit split of “whatever KW touches,” introductions to the heads of factories. Then he became infuriated when he couldn’t speak immediately with Rorsted.

Weeks later, in November 2019, the CEO, along with Liedtke, Wexler and other Adidas officials, hosted him in Portland, eager to work things out.

When West arrived at the office, he appeared to notice only the shoes lining the floor, awaiting his approval. He began lobbing sneakers around the room. Then he stomped out.

Still, the top executives were committed. They would help him build up a Yeezy campus in Cody and introduce him to factory owners. Most significant, the company would provide West with additional money each year.

West, who objected to advertising and other traditional promotion, had insisted that Adidas’ money was better spent on anything that drew public attention to him. So the executives had agreed to replace the Yeezy marketing budget with a $100 million annual fund that West could spend with less oversight.

‘Adidas Can’t Drop Me'

Last September, West arrived at Adidas’ Los Angeles office to meet with company executives.

Yeezy sales were on track to reach $1.8 billion in 2022, according to Adidas projections. West’s grievances had also multiplied.

Under their contract, Adidas owned the designs they had created together — including more than 250 Yeezys. But as the company released shoes closely resembling Yeezys under other names, West cried theft and demanded a cut of sales.

By then, some of his closest contacts at Adidas — Wexler, Anfuso and Liedtke — had left, and he appeared to have lost faith in those who remained.

So he went to war: railing on social media about the CEO and the supervisory board and persuading high-profile friends, like Diddy and Swizz Beatz, to threaten a boycott.

At the Yeezy fashion show in Paris in October, he posed with conservative commentator Candace Owens, who has attacked the Black Lives Matter movement and urged Black voters to leave the Democratic Party, in shirts that said “White Lives Matter” — a slogan associated with white supremacists. After she posted a photo online, fueling outrage, he berated critics who accused him of being racially insensitive, then engaged in hostile interviews and social media posts. He called Black Lives Matter a scam. He announced he would go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE.”

During an interview on the “Drink Champs” podcast, he spread conspiracy theories about Jews controlling the levers of power and insisted that the police hadn’t killed George Floyd. Then he taunted, “I can say antisemitic things, and Adidas can’t drop me. Now what?”

Politicians, Hollywood corporate heads, fellow entertainers and Jewish leaders condemned the comments, saying his behavior emboldened others to embrace bigotry. Kardashian, whose divorce from West would soon be final, also spoke out.

On Oct. 25, nine days after West declared that Adidas wouldn’t end his deal, the company did just that.

“Ye’s recent comments and actions have been unacceptable, hateful and dangerous,” an Adidas statement said, “and they violate the company’s values of diversity and inclusion, mutual respect and fairness.

Even then, West was unrepentant; in the following months, he went on to explicitly state his fondness for Hitler, deny the Holocaust and tweet an image combining the Star of David with a swastika.

And behind the scenes, the artist fought back against Adidas.

As they began arbitration, a requirement under their contract, Adidas accused him of reducing a multibillion-dollar collaboration to “economic rubble” with his offensive comments. West charged that Adidas had devalued Yeezys, saying that the company’s “greed and opportunism have no bounds.” Adidas would not comment on the arbitration, citing confidentiality.

Even as they squared off in arbitration, Adidas and West came to an agreement that served their common interest. Starting in May, Adidas began releasing the remaining inventory of Yeezys. A portion of the proceeds would go to the Anti-Defamation League, another group battling antisemitism and an organization started by Floyd’s family.

But most of the revenue would go to Adidas, and West was entitled to royalties.

The shoes took in about $437 million in sales through June. Crediting the recent Yeezy drops, along with its other products, Adidas has significantly improved its forecast for the year, revising an earlier projected operating loss of more than $700 million to about $100 million.