Myanmar’s decade-long experiment in conditional democracy just ended in a textbook example of a coup — a coup that was a pre-emptive strike.

In the early hours of Monday, as the new national Parliament was scheduled to convene for its first session, the military, known as the Tatmadaw, announced that it was taking over, alleging fraud during the last general elections in November. It arrested Daw Aung San Suu Kyi — formally the state counselor, but really the country’s de facto leader — other senior officials and a handful of prominent political and social figures.

Multiple reports suggest that Suu Kyi's government barred huge numbers of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities, who typically support their own political parties, from participating in national elections.

The country’s military junta, after decades of iron-fisted rule, had in 2011 started handing off power to a civilian government before Suu Kyi's party won in 2015. Both sides have spent much of the last few years escalating a bitter and increasingly zero-sum rivalry.

Here are the 5 things you need to know about the Myanmar coup d'état:

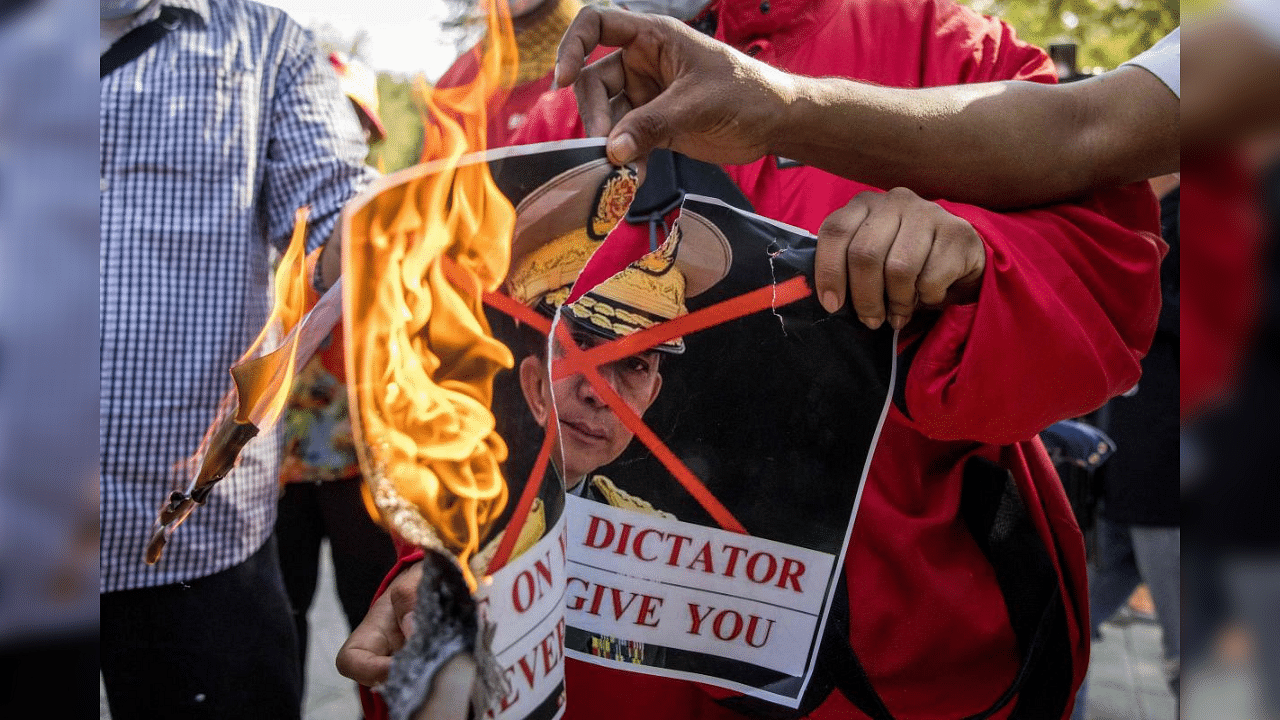

1. The Tatmadaw invoked the Constitution (which it drafted back in 2008) to declare a state of emergency for a year. The already powerful commander in chief, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, is now essentially a dictator. He has pledged “to practice the genuine, discipline-flourishing multiparty democratic system in a fair manner” and has announced plans to hold another election at an unspecified date.

2. The military has manufactured a crisis so that it could step in again as the purported savior of the Constitution and the country while vanquishing an ever-popular political foe. The military still has much constitutionally guaranteed power: It controls the ministries of defense, home affairs and border affairs, 25 per cent of seats in the national and regional assemblies are reserved for the military and it has veto authority over amendments to key provisions of the Constitution.

3. After one term in office, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy bested its own landslide victory of 2015. The party emerged victorious in the November election, which seemed to upset the uneasy balance of power in place in the eyes of the Tatmadaw. The military saw it as a threat to its prerogatives and privileges.

4. There is much animus between Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, and General Min Aung Hlaing. The two have rarely met since 2015 except at public events. Beyond personal tensions, there is institutional antagonism. For some three decades, the NLD was subject to crushing persecution at the hands of the Tatmadaw and the security forces. Hundreds of the party’s members were arrested, tortured, killed or driven into exile.

5. Hlaing was scheduled to step down this year, after the retirement age for his position was moved five years ago, from 60 to 65. There are murmurs that the General is concerned about being vulnerable to prosecution once he is out of office, at least internationally, for his leadership over the ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims.