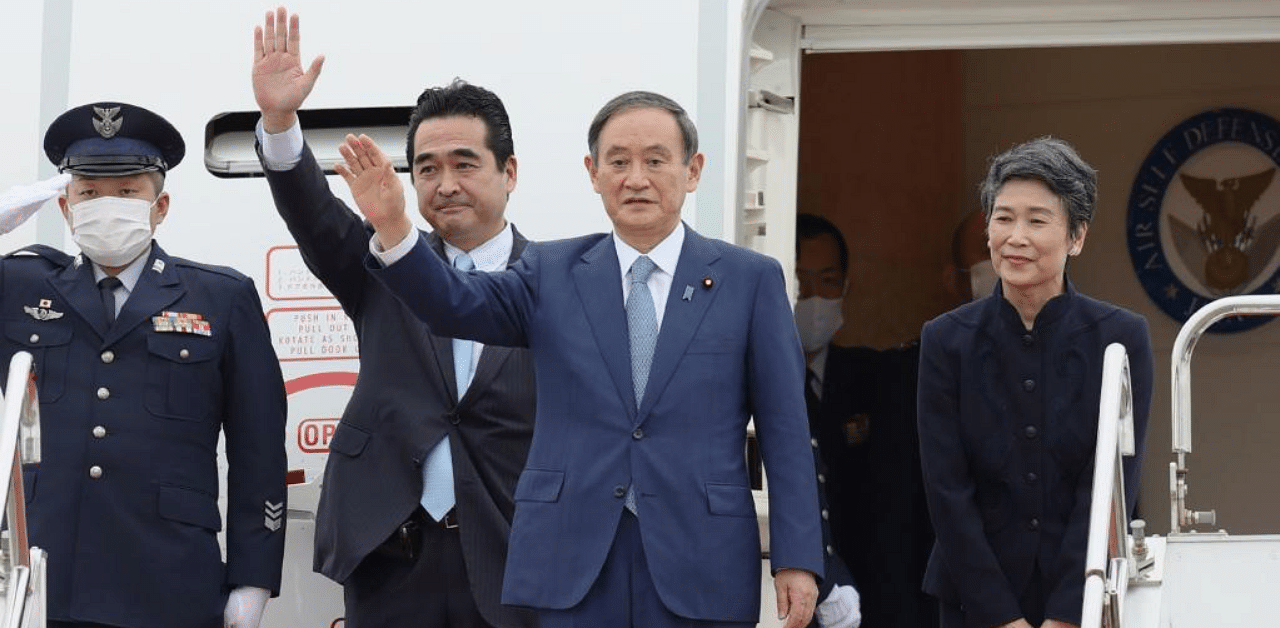

Japan's new prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, left Sunday on his first overseas foray since taking over from his former boss Shinzo Abe last month, heading to Vietnam and Indonesia.

The choice to visit Southeast Asia underscores Japan's efforts to counter Chinese influence and build stronger economic and defense ties in the region, much in line with Abe's vision of “Free and Open Indo-Pacific" that he has pushed with Washington.

“ASEAN countries are our extremely important partners to achieving the 'Free and Open Indo-Pacific' that Japan has been promoting,” Suga told reporters before boarding his flight to Hanoi. “As part of Indo-Pacific nations, Japan is committed to contribute to the region and I will clearly convey this to the people in and outside of our country."

His trip also reflects pandemic realities. With the US tied up with the November 3 election, Suga was unable to head to Washington straight away for talks with Japan's most important ally after he replaced Abe, who resigned for health reasons.

As he emerges from Abe's shadow with promises to “work for the people”, Suga is proving in some ways to be even more hard line. It has raised hackles within Japan and could rile neighbours, already disgruntled by Abe's nationalist agenda.

Abe had vowed to restore Japan's waning diplomatic stature and national pride by promoting ultra-nationalistic policies such as traditional family values and amending the post-World War II pacifist constitution to allow a greater overseas military role for his country.

Suga is expected to sign a defense equipment and technology transfer agreement with Vietnam as part of efforts to promote exports of Japanese-made military equipment. It's a signal that Suga is certain to follow in Abe's footsteps in diplomacy.

At home, Suga was best known for his behind-the-scenes work pushing Abe's agenda as chief Cabinet secretary. He has deftly used his modest background as the son of a strawberry farmer and a teacher and his low-profile, hardworking style to craft a more populist image than his predecessor.

With much of the world, including Japan, occupied with battling the pandemic, Suga is focusing more on delivering results. So far, he appears to be trying to distinguish himself from Abe by pumping out a hodge-podge of consumer-friendly policies meant to showcase his practical and quick work.

With national elections expected within months, there is little time to waste.

"What is always on my mind is to tackle what needs to be accomplished without hesitation and quickly, and start from whatever is possible ... and let the people recognize the change,” Suga told reporters on Friday as he marked his first month in office.

He has ordered his Cabinet to rush through approvals of several projects such as eliminating the requirement for Japanese-style “hanko” stamps, widely used in place of signatures on business and government documents. He is forging ahead with his earlier efforts to lower cellphone rates and promote use of computers and online government and business.

Tackling Japan's low birthrate and shrinking population head-on, he favours granting insurance coverage for infertility treatments.

“So far, Prime Minister Suga is working on policies that are easy to understand and popular to many people, as his administration apparently aims to maintain high support ratings,” said Ryosuke Nishida, a sociologist at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

At the same time, Suga's refusal to approve the appointments of six professors out of a slate of 105 to the state-funded Science Council of Japan has drawn accusations that he is trying to muzzle dissent and impinge on academic freedoms.

The flap looks unlikely to balloon into a serious crisis for Suga, who has not given any explanation apart from saying that his decision was legal and that the group of academics that advises and checks government policies should be acceptable to the public.

But it added to concerns that Suga might be more forthright than Abe in quashing opposition: The council, set up in 1949, has repeatedly opposed military technology research at universities, most recently in 2017. Its objections to government funding for such research is contrary to Abe's efforts to build up Japan's military capability.

Many Japanese, especially academics, are wary of abuse of power given the country's history of militarism and anti-communist campaigns after the World War II.

Historian Masayasu Hosaka, writing in the Mainichi newspaper, described it as a “purge.” The surprise decision sent support ratings for Suga's Cabinet to just above 50 per cent last week from well above 60% shortly after he took office.

Adding to unease over possible interference in academic freedom, the Education Ministry urged public schools to display a black cloth symbolising mourning along with the national flag, and to hold a moment of silence to show respect for late Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, whose state-funded funeral was held on Saturday.

Such moves would come as no surprise under Abe, who as grandson of wartime leader Nobusuke Kishi and heir to a political dynasty stuck to his ultra-conservative agenda.

But while Suga's own personal ideology is unknown, he followed Abe's example in making ritual donations of religious ornaments Saturday to the Yasukuni Shrine to pay respect to the war dead. China and South Korea consider the shrine, which also commemorates executed Japanese war criminals, a symbol of Japan's militaristic past. (