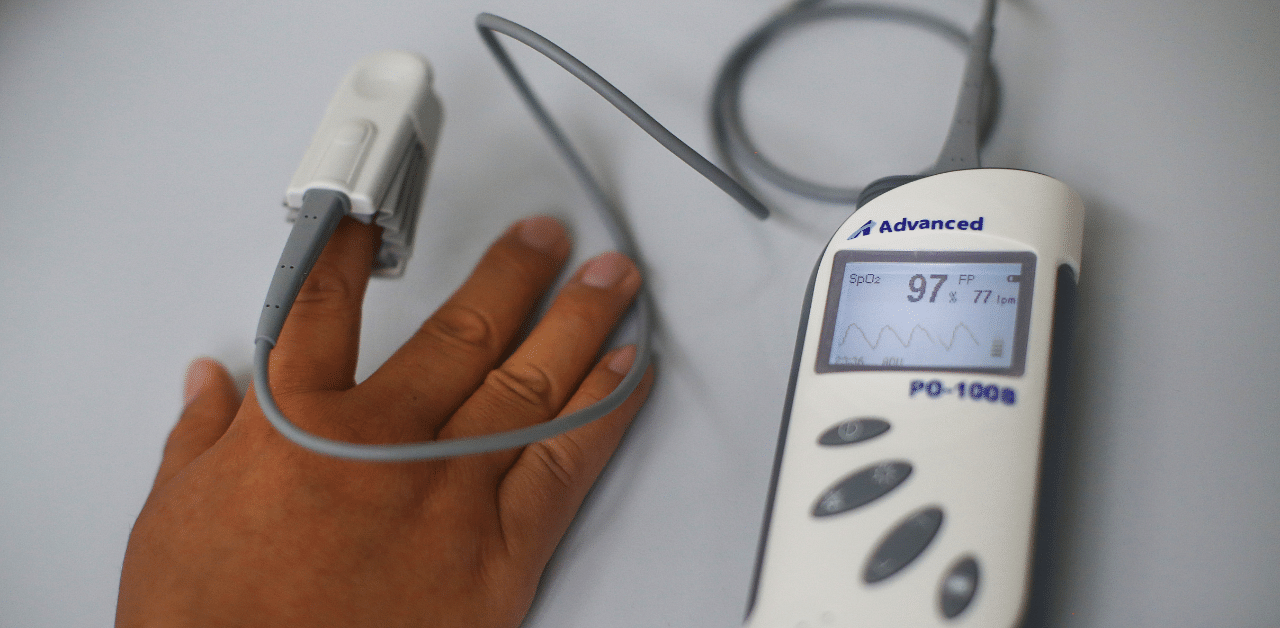

Pulse oximeters are one of the most commonly used tools in medicine. The small devices, which resemble a clothespin, measure blood oxygen when clipped onto a fingertip, and they can quickly indicate whether a patient needs urgent medical care.

Health providers use them when they take vital signs and when they evaluate patients for treatment. Ever since the pandemic started, doctors have encouraged patients with Covid-19 to use them at home.

But in people with dark skin, the devices can provide misleading results in more than 1 in 10 people, according to a new study.

The findings, which were published last week as a letter to the editor of a top medical journal, sent ripples of dismay through the medical community, which relies heavily on the devices to decide whether to admit patients or send them home.

During the coronavirus outbreaks, the inexpensive devices have also become a widely sold item online, used by consumers to monitor their own oxygen levels at home when doctors have told them they are not sick enough to be hospitalized.

The report also stirred concerns because the pandemic is taking a disproportionate toll on Black and Hispanic Americans, drawing attention to racial health disparities and prompting soul-searching among doctors about the bias that permeates the practice of medicine. There have been several reports of acutely ill Black patients who sought medical care, only to be turned away, and studies have found that African Americans were hospitalized at higher rates, suggesting delays in access to medical care.

The researchers who conducted the oximeter study said they were surprised by the findings. Although scientific reports of the inaccuracies have been published in the past, they did not receive widespread attention or get incorporated into medical training.

“I think most of the medical community has been operating on the assumption that pulse oximetry is quite accurate,” said Dr Michael W. Sjoding, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School and lead author of the new report, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. “I’m a trained pulmonologist and critical care physician, and I had no understanding that the pulse ox was potentially inaccurate — and that I was missing hypoxemia in a certain minority of patients.”

Dr Utibe Essien, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who studies racial disparities in cardiovascular disease, noted that doctors practising telemedicine have relied on reporting from these devices.

“If we cannot ensure that its definition of low oxygen in people, especially Black people, is accurate, there is a concern that it is increasing or driving disparities,” he said.

Pulse oximeters work by shining two wavelengths of light, red light and infrared light, that pass through the skin of a finger.

The device detects the colour of blood, which differs depending on the amount of oxygen. Oxygenated blood is bright cherry red, and deoxygenated blood has a more purplish hue. Depending on the hue, different amounts of light from the device are absorbed, and the oximeter analyzes the proportions of the absorption and calculates the amount of oxygen. Researchers suspect that the inaccurate readings may be occurring because of the way the light is absorbed by darker skin pigments.

Dr Philip Bickler, director of the hypoxia research laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco, which tests the performance of pulse oximeters, said the simplest way to explain the inaccuracies in patients with darker skin is that the pigment “scatters the light around, so the signal is reduced. It’s like adding static to your radio signal. You get more noise, less signal.” (Dark nail polish also reduces the accuracy, as do cold fingers.)

Generally, health providers treating patients take many metrics into account, including imaging scans, inflammatory markers and other clinical signs, said Dr. Darshali Vyas, a resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital who has done research on medical decision-making tools that incorporate race. But, she said, “pulse oximetry remains one of the mainstays.”

The new findings “help quantify the potential harm done by a ubiquitous medical tool that may normalize white skin as the default,” Vyas said in an email. She added that this could be “especially concerning” for doctors using the readings to adjust the amount of supplemental oxygen they give Covid patients and to determine transfers to intensive care.

The study compared pulse oximeter measures with values obtained from a more invasive type of test, called an arterial blood gas test, carried out in the same patients at about the same time. Arterial blood gas tests are used more rarely because they require drawing blood from an artery, which is a more invasive procedure than drawing blood from a vein.

The analysis, of 10,789 paired test results from 1,333 white patients and 276 Black patients hospitalized at the University of Michigan earlier this year, found that pulse oximetry overestimated oxygen levels 3.6 per cent of the time in white patients but got it wrong nearly 12 per cent of the time, or more than three times more often, in Black patients.

In these patients, the pulse oximeter measures erroneously indicated the oxygen saturation level was between 92 per cent and 96 per cent, when it was actually as low as 88% (the results were adjusted for age, sex and cardiovascular disease).

Oxygen levels below 95 per cent are considered abnormal, so “a small difference in pulse oximetry value in this range of 92 to 96 per cent could be the difference in deciding whether the patient is really sick or not really sick, or needs different treatment or not,” Sjoding said.

Another analysis in the study examined a multi-hospital database to compare 37,308 similar paired test results from intensive care patients who had been hospitalized at 178 medical centers in 2014 and 2015. That analysis, which was not adjusted, found similar discrepancies.

Sjoding said he and his colleagues embarked on the study after hospitals in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which typically care for a predominantly white patient population, received a large influx of critically ill Covid patients from Detroit, many of whom were African American.

“We started seeing some discrepancies with arterial blood gas, and we didn’t know what to make of it,” he said.

He recalled reading an article published in The Boston Review in August about racial disparities in the accuracy of pulse oximeter readings. The writer of that article, Amy Moran-Thomas, became interested in the device after buying one when her husband was sick with Covid. She dug up scientific papers published as far back as 2005 and 2007 that reported inaccuracies in pulse oximeter readings in dark-skinned individuals at low oxygen saturation levels.

Sjoding and his colleagues decided to do a study using data that had already been collected during routine inpatient care at the hospital.

“What we were seeing anecdotally was exactly what we ended up showing in the final paper, that on the monitor in the patient’s room, the pulse oximeter would be reading ‘normal,’ but when we got an arterial blood gas, the saturation on the gas was low,” he said.

Bickler was the author of some of the earlier studies that reported on inaccuracies in people with darkly pigmented skin. He said oximetry errors have been known from lab studies for quite some time, but the new paper provides real-world evidence.

“It’s apparent that there are racial differences in how oximeters perform — we pointed that out way back 15 years ago,” he said. “The biggest issue is why it hasn’t been fixed. Now the Covid pandemic has brought this all to the fore: All of a sudden the medical system is overwhelmed with patients with low oxygen.”

Bickler’s article in 2005 suggested the devices could be improved with a setting that adjusts to a different calibration for a darker pigmented skin.

“I’m not sure it’s easy to do, but there should be a way of fixing this,” he said.

The paper also suggested the devices carry warning labels about the potential for overestimating oxygen levels in dark-skinned patients.

Findings of similar disparities have also been reported in physical fitness devices.

Sjoding and his colleagues are not advising the oximeters be discarded. The vast majority of readings are accurate, he said.

“The pulse ox is an amazing tool, but we treat it like it’s way more accurate than it actually is,” he said.

Steven Gay, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Michigan who is one of the report’s other authors, said the study is a reminder to look at patients holistically and individually.

“To take the best care of our patients, we have to know these things, so we don’t make assumptions that a patient is doing well, just because the data isn’t what it’s supposed to be,” he said. “It reminds us that as much as we speak about medicine as a science, there is an art to it.”