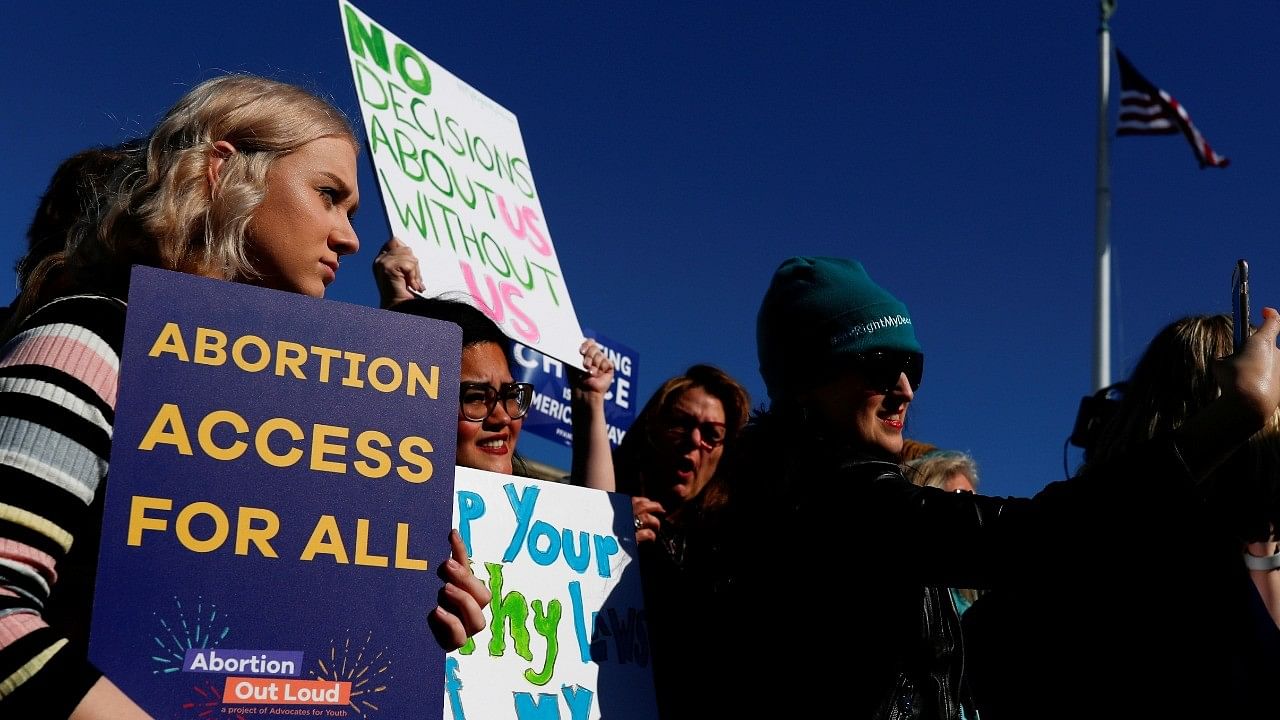

At least a half-dozen Republican candidates have put out direct-to-camera ads declaring their opposition to a federal abortion ban.

Credit: Reuters Photo

Josh Riley, the Democratic challenger running for Congress in New York’s 19th District, has a clear message on abortion: “I believe that women’s health care decisions are women’s health care decisions and that politicians should stay the hell out of it.”

And his Republican opponent, incumbent Rep. Marc Molinaro, is saying nearly the same thing: “I believe health care decisions should be between a woman and her doctor, not Washington.”

Across the country’s most competitive House races, Republicans have spent months trying to redefine themselves on abortion, going so far as to borrow language that would not feel out of place at a rally of Vice President Kamala Harris. Many Republicans who until recently backed federal abortion restrictions are now saying the issue should be left to the states.

At least a half-dozen Republican candidates have put out direct-to-camera ads declaring their opposition to a federal abortion ban. Instead, they say, they support exceptions to existing state laws and back protections for reproductive health care, such as IVF.

Democrats have raised the possibility of a nationwide abortion ban should Republicans win in November, and they are framing the campaign as another referendum on the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade. They are hoping to continue their run of electoral successes since the 2022 decision to win back control of the House.

Any new federal legislation on abortion would have to pass both the House and the Senate and be signed by the president to become law. But whichever party emerges with a majority in the House will have the ability to dictate the legislative agenda, including whether measures to restrict or expand abortion access have the chance to pass.

Republicans in California and New York, in particular, who are running in swing districts in blue states that favor abortion rights, have felt the most pressure to address the issue directly. “If we don’t talk about the issue, we become whatever the Democrats say we are,” said Will Reinert, press secretary for the National Republican Congressional Committee.

To better understand how abortion is playing a role in these campaigns, The New York Times surveyed candidates from both parties in the most competitive House races about their support for federal limits on abortion. The Times also looked at voting records, issues listed on campaign websites, debate and media coverage, and endorsements from major abortion rights and anti-abortion groups.

The Times survey showed that although Republicans are notably focused on what they will not do on abortion at the federal level, their Democratic opponents are talking about what they will do to protect abortion rights. Nearly all the Democratic candidates said they supported restoring the protections of Roe v. Wade, which would allow access to abortion until fetal viability, or about 24 weeks, in every state.

In attack ads, Democrats are pointing to their opponents’ voting records or past statements as evidence of extremism — despite what they may be saying now.

More broadly, abortion rights groups said Republicans are misleading voters by claiming they do not support an outright abortion “ban,” when they might support a federal “limit” or “standard,” such as the 15-week proposal put forward by Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., in 2022.

“They are playing around with the semantics; they are clearly testing out different framing and messaging in an attempt to try and deceive voters because they realise how politically unpopular their policy stances are,” said Jessica Arons, a director of policy and government affairs at the American Civil Liberties Union.

Republicans in the Times survey almost universally declined to answer questions about gestational limits. Only one, Rep. Don Bacon of Nebraska, said he supported a specific federal limit, in the third trimester.

The Republican shift away from publicly supporting a federal ban follows the lead of former President Donald Trump, who has changed his own language on the issue after seeing the electoral backlash to the Dobbs decision.

As recently as 2021, a majority of House Republicans — including seven incumbents in this year’s toss-up races — co-sponsored the Life at Conception Act, a bill that would have amounted to a nationwide abortion ban. This year, Rep. Scott Perry of Pennsylvania’s 10th District was the only incumbent in a competitive race to stay on as a co-sponsor.

Two Republican incumbents who now say they oppose a national ban — Reps. Ken Calvert and David Valadao in California — voted in favor of a 20-week ban that passed the House in 2017. Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks, an Iowa Republican, co-sponsored a 15-week ban on abortion in 2022. She did not respond to questions about whether she still supports it.

Other Republicans described themselves as personally “pro-life” but said they accepted the abortion laws in place in their states. Rob Bresnahan Jr., a challenger in Pennsylvania’s 8th District, said he supported the state’s current law, which allows abortion until 24 weeks.

Democrats, when they were not attacking Republicans, leaned into language about personal freedom, with many in the survey saying the government should not be involved in medical decisions.

Another common refrain was that the decision to have an abortion should be “between a woman and her doctor.” Two Democrats used similar language rather than explicitly calling for federal abortion protections.

By appearing to moderate their stance on abortion, candidates have risked losing the backing of prominent advocacy groups. Only three Republicans in the toss-up races received an endorsement from Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, and seven received one from National Right to Life.

Two major abortion rights groups, by contrast, endorsed nearly all the Democratic candidates. Planned Parenthood — whose political action fund is pouring $40 million into the campaign — endorsed all but six candidates, while Reproductive Freedom for All endorsed all but four.

Rep. Jared Golden — the Democratic incumbent in Maine’s 2nd Congressional District, an area that Trump won by 6 points in 2020 — did not get Planned Parenthood’s endorsement this year. He said the reason was his vote for the 2024 defense policy bill, which included an amendment blocking reimbursement for abortion travel costs for service members.

Golden said he was not concerned about the lack of support from the group, pointing instead to his co-sponsorship of the Women’s Health Protection Act, a bill to restore the protections of Roe.

“I’m quite confident that voters in Maine know where I stand,” he said.