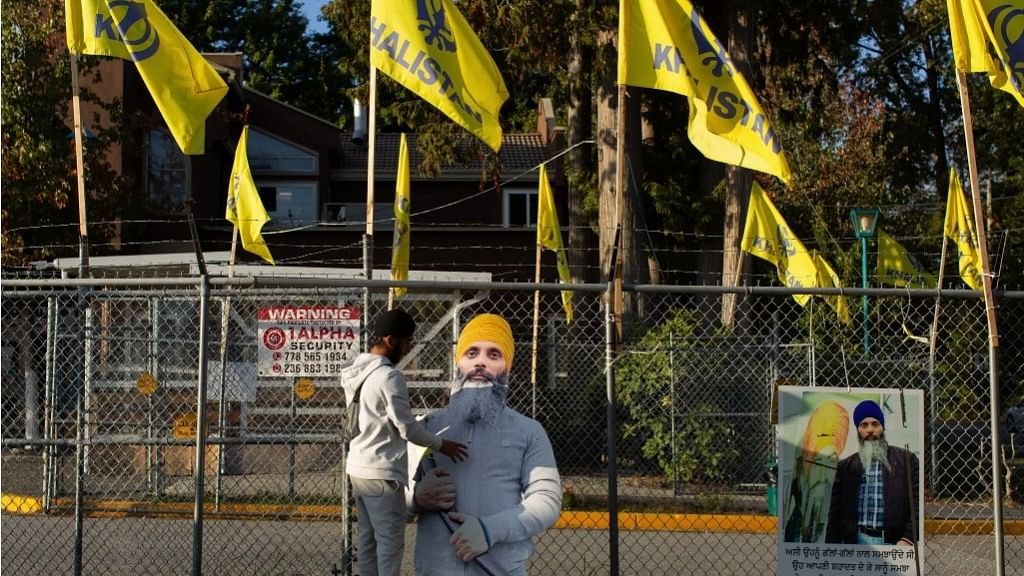

A memorial for Hardeep Singh Nijjar on the grounds of the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara temple in Surrey.

Credit: International New York Times Photo

The markers of separatism are everywhere at the temple. Dozens of yellow flags of Khalistan — a homeland that Sikh separatists want to create in the Punjab region of India — fly in and around the grounds of the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara temple near Vancouver.

In a ground-floor hall, where the faithful were socialising and eating, the walls are lined with scores of framed photographs of slain separatist leaders. Now, a portrait of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, holding the symbolic curved sword of devout men, has been added to a wall with four pushpins, still unframed.

Nijjar was gunned down outside the temple in June, a killing that Canada has accused India of orchestrating, starting a diplomatic skirmish that has culminated in a war of words between the two countries.

Nijjar had taken over leadership of the temple in 2019, and his ascension steered the temple in a far more strident and political direction, most likely rousing the suspicion of India, which labeled him a terrorist the following year.

On Monday, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that agents of the Indian government had carried out Nijjar’s execution on Canadian soil. The Indian government, which has long accused Canada of harboring Sikh extremists, strongly denied the accusation. Trudeau’s allegation, made so far without the presentation of evidence, led to tit-for-tat expulsions of senior diplomats.

Trudeau, who was in New York on Thursday for the United Nations General Assembly, told editors and reporters of The New York Times that he could not talk about the evidence behind his accusations.

“We’re not trying to provoke,” he said. “But when we have credible reasons to believe that this happened, you can’t shrug it off.”

The temple is the oldest, largest and most influential in Surrey, the city in British Columbia that is an epicenter of Canada’s large Sikh diaspora. At one time, when its leaders were friendly with India, it was a regular stop for visiting Indian officials.

Separatists gained control of the temple’s leadership in 2008, but they remained largely quiet about the most fraught aspect of Sikh separatism: criticism of the Indian state.

That changed under Nijjar’s leadership.

“The difference was how blunt Mr. Nijjar was in calling out the Indian state,” said Gurkeerat Singh, 30, a close associate of Nijjar and a lifelong temple member. “He was very blunt, unapologetic. Every single week, he would come on the stage and make this the main issue about what’s happening to our youth in Punjab and what the Indian state has committed against us.”

The temple, occupying several blocks, is one of the most visible focal points of Sikh life in Surrey, along with a sprawling outdoor mall, Payal Business Center, a couple of miles away.

How it became an outspoken advocate of separatism reflects the evolution of the Sikh community in Canada — the largest outside India — and the political emergence of second-generation immigrants, the children of Sikhs who fled to Canada after violence in India in the 1980s, experts said.

It is difficult to gauge what share of the Canadian Sikh population supports the separatism that Nijjar championed and that fueled his rise, experts said, but signs of this separatism are expressed more conspicuously than in the past — for example, in the referendum for an independent state of Khalistan that Nijjar and other leaders have been organizing in Sikh diaspora communities worldwide.

“There is now more visible, physical, tangible support for Khalistan,” said Indira Prahst, a sociologist at Langara College in Vancouver. “It’s more overt.”

No matter the breadth of the movement, the Indian government considered Nijjar a threat. It declared him a terrorist in 2020, accusing him of plotting an attack in India and of leading a terrorist group.

For Nijjar’s supporters, the charges were simply a way to discredit an inspirational figure who was rallying Sikhs around the goal of self-determination and fighting for their rights.

Nijjar, who was 45 when he was killed, was a teenager when he arrived in Canada in 1997 after years of deadly violence between Sikhs and the Indian government.

In 1984, Indian soldiers occupied one of the holiest Sikh places of worship in India, the Golden Temple, to remove militants after Sikh separatists had committed massacres of Hindus in Punjab, the state where Sikhs are a majority. Hundreds of Sikhs were killed, and thousands more were also killed after the prime minister at the time, Indira Gandhi, was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards.

Nijjar told his family about Sikh men who, fearing being targeted, had to take off their turbans and of friends who disappeared, his son Balraj Singh Nijjar, 21, said in an interview.

“He mentioned to me as well how he had been tortured in India in his teenage years and how that left him with a pain to this day,” the son said.

By the time Hardeep Nijjar arrived in 1997, the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara temple had existed for about two decades. First established in a house in Delta, a city about 10 miles southwest of Surrey, it was built in its current location in the late 1970s by the small Sikh community of mostly working-class immigrants who had immigrated to Canada in the preceding decades, said Shinder Purewal, an expert on Sikh nationalism at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey.

“Most of them were moderate Sikhs, who were not much practicing and who were rather integrated in Canadian society,” said Purewal, who has been going to the temple ever since it was first housed in a home. “Secular types who went to temple more for cultural rather than religious reasons.”

But the mass arrival of Sikhs after the violence of the 1980s changed the dynamics at this temple and others that opened in the region, pitting older arrivals who tended to foster friendly ties with the Indian consulate and newcomers who saw the Indian government as their sworn enemy.

“In the 1990s and 2000s, there were many skirmishes in temples between what you would call moderates and fundamentalists,” said Satwinder Bains, an expert on the Sikh community at the University of the Fraser Valley, adding that temple leaders were elected regularly by members.

In 2008, separatists advocating the homeland of Khalistan took over the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara temple. Today, in Surrey, where more than one-quarter of the city’s population identifies as Sikh, three out of a dozen temples are outwardly separatist, with the rest remaining mostly neutral, Purewal said.

The separatist movement has become more visible with the emergence of second-generation Canadian Sikhs who have heard stories of the violence in the 1980s from parents and grandparents, said Prahst, the sociologist.

“Members of the second generation are now hearing more about what happened in 1984 in India, and that’s striking a very deep chord in their hearts, their psyche and their identity,” Prahst said.

Singh, the 30-year-old who was close to Nijjar, was born and grew up in British Columbia. He became politically aware after listening to stories from his grandparents, he said.

“Our parents are first-generation, and they made us financially stable,” Singh said. “So we’re able to come out and speak about these issues.”

Critics say that the separatist movement is largely a product of diaspora communities and now has little resonance among Sikhs in India. Separatists say that Sikhs in India are simply too afraid to speak.

At the Guru Nanak Sikh Gurdwara temple, worshippers, including newcomers, expressed a variety of opinions about the separatist movement.

Prabhjot Kaur, 30, who arrived in Surrey a few months ago to study business management and planned to return to India to work, said she came to the temple several times a week for religious reasons and did not believe an independent Sikh state was viable.

“Who will invest in such a state?” Kaur said, but she added that the killing of Nijjar was unacceptable.

A memorial has been erected in the temple’s parking lot, where Nijjar was shot dead by two heavyset men while driving his pickup truck last June. A sign describes him as the first martyr of the Khalistan movement in Canada.

Nijjar was on his way home from the temple, where he had told congregants of his fears of being targeted by India. In his pickup, he called his wife, who put him on speakerphone, recalled his son Balraj.

“What’s for dinner?” asked Nijjar who, depending on the answer, sometimes ordered takeout, his son said.

But it was Father’s Day, and his favorites, including a sweet dessert called seviyan, were waiting for him at home.

“He got even happier,” the son said, “and he told us, ‘Keep that warm. I’m coming right now.’”