Russia expects to produce primarily freeze-dried Sputnik V coronavirus vaccine doses by the spring, a top official said, eliminating the need for transport at ultra-low temperatures as part of an ambitious plan to inoculate its population.

Vaccine developers globally are scrambling to work out how to ship and store their vials, some of which must be kept in specialised freezers at extremely low temperatures.

The logistical challenge was brought into sharp focus after promising interim trial data for the vaccine developed by BioNTech and Pfizer, a major breakthrough in the race to curb the pandemic.

This vaccine needs to be shipped and stored at minus 70 degrees Celsius, equivalent to an Antarctic winter, posing a challenge for even the most sophisticated hospitals in the United States.

It also puts it out of reach for the moment for many poor countries.

Transportation is a pressing issue for Russia, which has many extremely remote settlements and has already begun rolling out a programme of mass inoculation of frontline medical workers across the country, though human trials of Sputnik V are not yet complete.

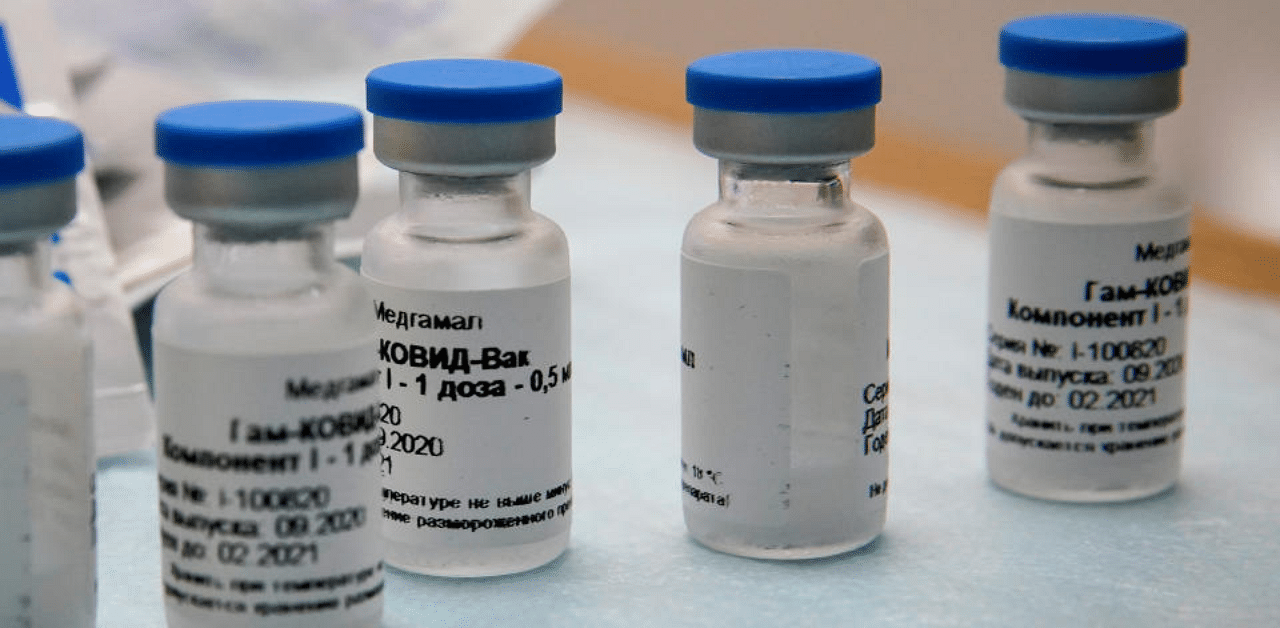

Whether being trucked across Siberia or flown to the far reaches of the Arctic, its vials must be stored at minus 18 degrees Celsius or below, according to the Gamaleya Institute which developed the shot.

But Russia has also been testing a version that has undergone lyophilisation, turning the liquid vaccine into a dry, white mass that can be stored at normal fridge temperatures of 2 to 8 degrees Celsius (35.6-46.4°F). It is then diluted before injection.

Russia has not previously disclosed how many doses of freeze-dried vaccine it is planning to produce. But Kirill Dmitriev, head of the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), which is backing and marketing the vaccine, told Reuters it would soon be the main focus.

"We expect that, starting roughly from February, we will switch mainly to the lyophilised form," he said. "A large proportion of doses, if not a majority, will be specifically in this form.

"We have conducted trials that confirm that the immune response to the lyophilised form is the same as to the standard form of the vaccine."

Interim results for the vaccine in liquid form showed the shot to be 92% effective.

Lead scientist at the Gamaleya Institute, Alexander Gintsburg, said in an interview with Reuters earlier this year that freeze-drying was not yet a primary focus, as lyophilisate is more expensive and takes longer to produce.

However, Dmitriev said that the process was not significantly more expensive, and that the main limitation is the time needed to acquire additional equipment.

Russia plans to produce around 2 million doses of Sputnik V this year, ramping up to 15 million per month by the spring.

Contracts seen by Reuters in the state tender register show that the Gamaleya Institute placed an order for materials from laboratory supplier Dia-M to be used for packaging 2.9 million doses of the shot in liquid form, and 720,000 doses freeze-dried. The order must be fulfilled by Dec. 21.

The health ministry, which supervises the Gamaleya Institute, did not comment on the contracts. Dia-M also did not respond to a request for comment.

Freeze-drying, if applied widely, could give Russia an advantage in some export markets.

The health secretary of the Brazilian state of Bahia told Reuters he had ruled out buying the vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech as they required ultra-cold freezers for transportation.

Bahia signed a deal with Russia for 50 million doses of Sputnik V in September.

Russia is not alone in looking at freeze-drying.

In Japan, Daiichi Sankyo Co is making a so-called messenger RNA (mRNA)-based candidate which it hopes will give it an edge for storing at higher temperatures. The technology uses a chemical messenger to instruct cells to make proteins that mimic the outer surface of the coronavirus, thereby creating immunity.

"We believe we can offer a much, much better condition (for storage)," said Masayuki Yabuta, head of the company's biologics division. "Freeze-dried is the best formulation."

VACCINE SPETSNAZ

The technique would be particularly useful for mRNA vaccines, such as the one developed by Pfizer and BioNTech, because of the ultra-low temperature storage needs, Anna Blakney, research fellow at Imperial College, said.

But it could also be used for other types of vaccines, including ones based on an adenovirus vector like in Russia.

"I think it just hasn't permeated into these big pharma companies yet," she said.

More testing may still be needed to check if freeze-drying affects a vaccine's efficacy.

"You have to show equivalency between the formulation. So someone that's vaccinated with the original formulation gets the same immune response as somebody vaccinated with the freeze-dried formulation," she said.

In late September, Russian authorities ran a test of the supply chain, sending small quantities of the vaccine in liquid form to every region of the country.

At the Moscow headquarters of logistics and courier firm Biocard, staff tracked the movements, receiving real-time updates on the temperature inside the special containers.

Containers are able to maintain a consistent temperature of minus 18.5 degrees for up to four days.

"The challenge is that ... you can't change the temperature by even half a degree, not even for a minute or a second," Oleg Baykov, Biocard director, said.

"So you have very little time," Baykov said. "We're like the Spetsnaz (rapid deployment forces) of the world of medical distribution."

Outside temperatures can also affect how long the containers are able to function. Winter weather in remote Russian towns, many built around oil or gas deposits, mean Biocard is gearing up to use helicopters for transporting some doses.

Russia has so far exported the vaccine to four destinations: Belarus, Venezuela, India and the United Arab Emirates. The Venezuela delivery was handled by delivery firm DHL, Baykov said, which also placed an order with Biocard for its temperature-controlled containers for the trip.