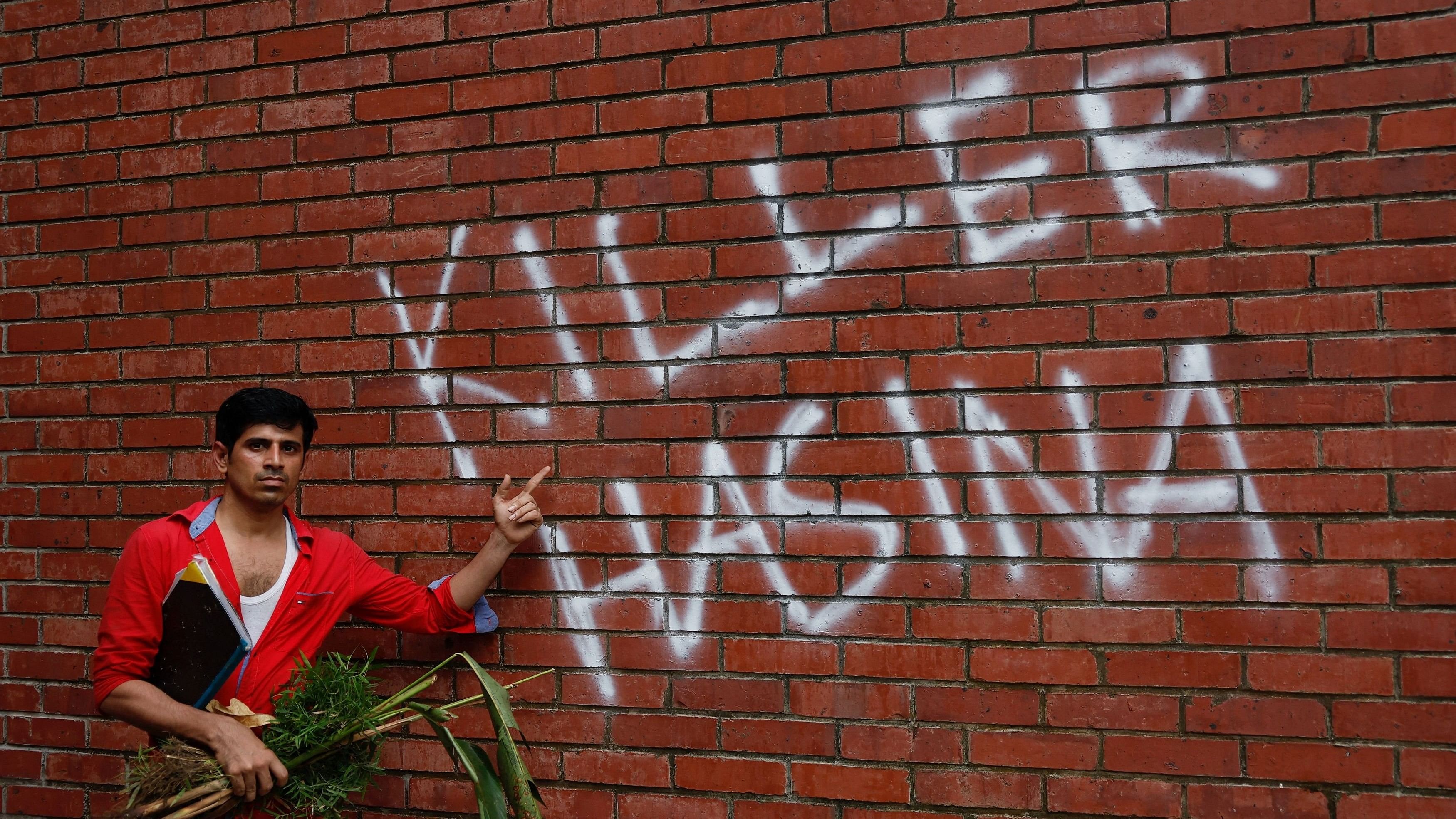

A man poses at the Ganabhaban, the Prime Minister's residence, after the resignation Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in Dhaka, Bangladesh, August 5, 2024.

Credit: Reuters Photo

By Kai Schultz, Dan Strumpf and Arun Devnath

The end was abrupt and unforgiving for one of Asia’s longest-serving leaders.

After enduring weeks of protests demanding her resignation, Sheikh Hasina saw her 15-year rule as Bangladesh’s prime minister unravel over the course of a bloody weekend that left scores of people dead. It culminated Monday with a mob ransacking her residence and the military forcing her to flee the country.

Her sudden departure marked the end of a run that saw Hasina, 76, turn Bangladesh into both an economic success story and a case study in the pitfalls of authoritarian rule. Even as surging exports of garments and other goods lifted millions out of poverty, her increasing suppression of political opponents sowed the seeds of her downfall.

Yet what comes next is unclear. Bangladesh’s army, no stranger to coups, is now looking to set up an interim government that may exclude Hasina’s Awami League, which won about 80 per cent of parliamentary seats in a boycotted vote in January. While President Mohammed Shahabuddin vowed to hold elections “as soon as possible,” it’s unclear if her allies will be able to participate or return to power.

The best-case scenario is that the military follows a template from a coup in 2007, when the generals oversaw an interim government and peacefully relinquished power about two years later after an election won by Hasina’s party. Yet that outcome remains uncertain.

Bangladesh could also see the military hold on to power for an extended period or more violence as various factions jockey for power, according to Paul Staniland, a professor at the University of Chicago who researches political violence in South Asia. The country saw widespread looting and arson attacks after Hasina fled.

Protest leaders on Monday said they would resist any government that didn’t meet their demands, and have proposed Nobel Peace Prize-winning economist Muhammad Yunus, 84, to serve as the leader of the interim government. Yunus, who pioneered micro loans as a tool to fight poverty, has faced legal trouble under Hasina that he has called politically motivated.

“It’s difficult to be confident about exactly how the coming days play out,” Staniland said. “When push came to shove, the military was unwilling to try to violently repress the ever-growing protests, and this was the trigger for the end of her time in office.”

Internationally, the biggest immediate risks fall on neighboring India. The Hindu-dominant government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi turned Hasina’s more moderate administration into a close ally, viewing her as a bulwark against the Islamist opposition in Muslim-majority Bangladesh.

Modi’s government allowed Hasina to land in New Delhi on Monday, and sought to provide her safe passage onward to London. Yet it wasn’t clear if the UK would allow her to enter, and Hasina hasn’t made any public comments since she fled.

“The void in Bangladesh will likely be filled by forces that will undermine Indian security,” said Zorawar Daulet Singh, a strategic affairs expert in New Delhi who has authored several books on India’s foreign policy.

Bangladesh also relies on foreign assistance to avoid a financial crisis. While it secured $4.7 billion in loans from the International Monetary Fund last year, both Fitch Ratings and S&P Global Ratings have recently cut the nation’s credit score further into junk because of falling reserves. In July, Hasina’s government revealed it was in talks with China for a $5 billion yuan-denominated loan.

Bangladesh should have sufficient dollar reserves to finance its external deficit and debt repayments this year, according to Ankur Shukla, an economist with Bloomberg Economics in Mumbai. Still, he said, the consensus forecast for a 6.2% economic expansion in fiscal 2025 now looks unachievable as “political uncertainty will likely discourage investment and hit growth.”

Over the past few weeks, frustrations with Hasina’s regime reached a breaking point. When protesters initially took to the streets last month to oppose quotas that reserve government jobs for specific groups — a law many felt favored Hasina’s allies — her government met them with force. The demonstrations, largely led by students, quickly turned violent.

The demonstrators soon narrowed their list of demands to a single bullet point: Hasina must go. They swarmed the streets of Dhaka, the capital, torching government offices and clashing with security forces as the death toll climbed past 300 people — one of the worst spasms of violence in Bangladesh’s history. The military’s allegiance quickly began to shift, too, with some army officials refusing to use force against demonstrators.

By Monday, Hasina found herself departing Dhaka by helicopter as demonstrators raided Ganabhaban, her opulent official residence, walking away with furniture, vegetables and — for one looter at least — a live chicken. Elsewhere, demonstrators wielding hammers scaled a massive statue of her father, the country’s first president.

“Justice will be served for each death,” Bangladesh Army Chief Waker-Uz-Zaman said in a televised address on Monday. “Keep faith in the army.”

The military has a long history of intervening in Bangladeshi politics during times of instability. Over its history, Bangladesh has had three major army coups and some two dozen smaller rebellions — including one as recently as 2012 by some former and serving officers, which the military quashed.

“I expect the massive overwhelming popular support for her resignation made it inevitable, but the army will have made it clear they could not support another day of carnage,” said Naomi Hossain, professor of development studies at SOAS University of London.

To many, Hasina’s ouster was long in the making. For years, the prime minister entrenched her power in ruthless ways, her detractors say, pushing one of the few Muslim democracies toward authoritarianism. Hasina’s government often resorted to shutting off the internet or cutting phone services to silence criticism. And protesters were often met with bullets.

Hasina argued that these measures were necessary in a nation scarred by coups and political bloodshed. Tragedy touched her life early. In 1975, while she was on a trip to Europe, soldiers drove a tank into her house in Dhaka in a coup that killed most of her family, including her father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

The event profoundly shaped her approach to politics — and to those who crossed her.

Over the years, Hasina and her Awami League party blamed Bangladesh’s opposition for involvement in the killings. She reserved special hatred for her fiercest rival, former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, whom Hasina kept imprisoned or sidelined for the past decade — and who is now set to be freed.

Friction between the two women was so volatile that the military jailed both in 2007 on corruption charges — a plan that was known as the “minus two solution.”

After her release, Hasina returned to power in 2009 and never left. Under her rule, she vastly expanded Bangladesh’s garments sector, helping transform the South Asian nation from one of the most impoverished pockets of the world to a lower-middle-income economy. Western diplomats appreciated her efforts to root out Islamists from politics. And she was widely praised for her willingness to provide shelter to more than a million refugees from Myanmar in the late 2010s.

She drew Bangladesh closer to neighboring India, which backed her regime, and China. Hasina also maintained strong trade relations with the US, even as she drew criticism from Washington for her human rights record.

But the optimistic narrative began to unravel over the past year. Turnout for the most recent national election was abysmally low. The vote was boycotted by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, the main opposition, and the US called the vote neither free nor fair.

By hitting the streets, a large chunk of the nation’s 171 million people have now made their views clear.

“Bangladesh has entered into uncharted territory,” said Ali Riaz, distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University. “How soon will it return or move toward a civilian government is the most challenging task.”