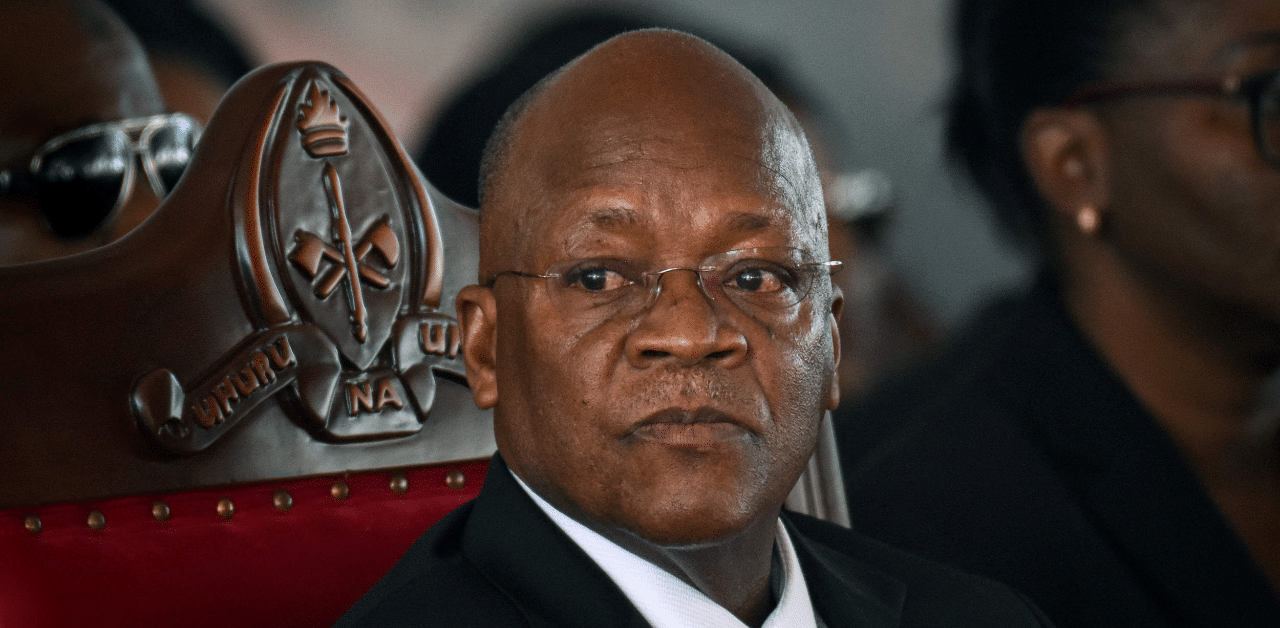

Tanzanian President John Magufuli, who died Wednesday aged 61, was once hailed for his no-nonsense attitude, but his swing to authoritarianism stifled democracy and allowed Covid-19 to run rampant.

Nicknamed the "Bulldozer," Magufuli died of what authorities said was a heart condition after weeks missing from public view without explanation, his absence sparking rumours he had caught coronavirus.

Magufuli came to power as a corruption-busting man of the people, but for many observers, his handling of the pandemic cast his leadership style into sharp relief.

The devout Christian claimed prayer had saved the country from Covid-19, championing praying over face masks and stopping virus figures from being published.

However by last month, cases were soaring to such an extent that the church, schools and other public institutions openly issued warnings about the spread of the virus.

Then the first vice president of semi-autonomous Zanzibar, Seif Sharif Hamad, died after his political party admitted he had the coronavirus.

Under mounting pressure, Magufuli appeared to concede the virus existed.

"When this respiratory disease erupted last year, we won because we put God first and took other measures. I'm sure we will win again if we do so this time around," he said.

"These diseases including the respiratory disease, exist, and have killed more people in other countries... we will all die, whether with this disease or malaria or any others. Let's go back to God, maybe we messed up somewhere."

Magufuli was first elected in 2015 on a fiery anti-corruption stance which endeared him to a population weary of graft scandals.

He quickly took wildly popular decisions, such as scrapping lavish independence day celebrations in favour of a street clean-up and banning unnecessary foreign trips for officials.

Several headline-grabbing incidents saw him showing up in person to demand why civil servants were not at their desks, while in one case officials were briefly jailed for lateness.

However his tendency to flout due process and act on a whim alarmed foreign allies over the squeezing of democracy in one of East Africa's most stable nations.

His re-election in October last year was dismissed as a sham by the opposition and diplomats.

It took place under an oppressive military presence after a crackdown on the opposition and the blocking of foreign media and observer teams.

"I think he is actually bulldozing everything, laws, human rights, everything," said Aikande Kwayu, a Tanzanian political analyst.

Under his rule a series of tough media laws were passed while arrests of journalists, activists and opposition members soared, and several opposition figures were killed.

Magufuli called for teenage mothers to be kicked out of schools, while rights groups slammed an unprecedented crackdown on the LGBT community under his rule.

Magufuli's supporters praised his crackdown on corruption, an energetic infrastructure drive as well as a shake-up in the mining industry which saw him renegotiating contracts with foreign companies to improve the country's share in its own resources.

He expanded free education, increased rural electrification and embarked on the construction of a key railway and a massive hydropower dam set to double electricity output in the country.

Magufuli was born in Tanzania's northwestern Chato district, on the shores of Lake Victoria, where he grew up in a grass-thatched home, herding cattle and selling milk and fish to support his family.

"I know what it means to be poor," he often said.

He was awarded a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Dar es Salaam and also spent some time studying at Britain's University of Salford.

Magufuli was a member of the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party, which has been in power since independence from Britain in the early 1960s.

A member of parliament since 1995, he held various cabinet portfolios, including livestock, fisheries and public works, where he earned the "Bulldozer" moniker.

Magufuli was married with five children.