On “The View,” the California senator spoke about “reimagining how we do public safety in America.”

On the Senate floor, she sparred with Rand Paul after the Kentucky Republican blocked a bill to make lynching a federal crime, and she is among the Democrats sponsoring policing legislation that would ban choke holds, racial profiling and no-knock warrants.

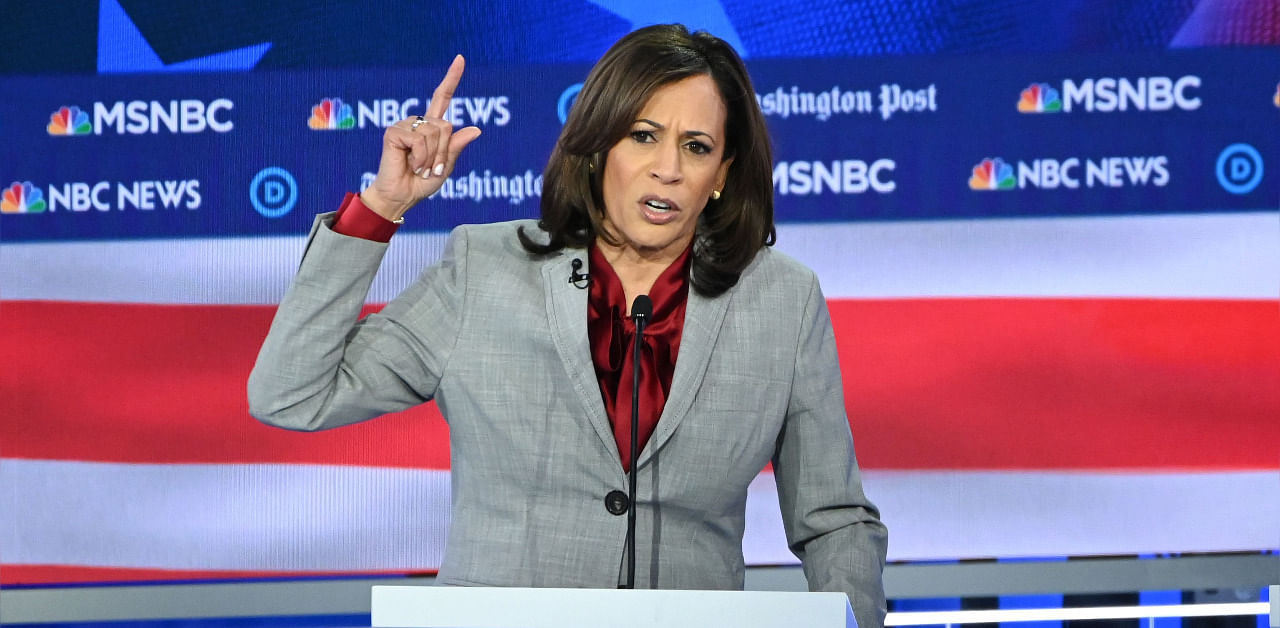

As a leading contender to be Joe Biden’s running mate in the final days before his decision, Harris has emerged as a strong voice on issues of police misconduct that seem certain to be central to the campaign. Yet in her own unsuccessful presidential run, she struggled to reconcile her calls for reform with her record on these same issues during a long career in law enforcement.

Since becoming California’s attorney general in 2011, she had largely avoided intervening in cases involving killings by police.

Then, amid the national outrage stoked by the 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, came pleas for her to investigate a series of police shootings in San Francisco, where she had previously been district attorney. She did not step in. Except in extraordinary circumstances, she said, it was not her job.

Still, her approach was subtly shifting. By the end of her tenure in 2016, she had proposed a modest expansion of her office’s powers to investigate police misconduct, begun reviews of two municipal police departments and backed a Justice Department investigation in San Francisco.

Critics saw her taking baby steps when bold reform was needed.

The daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father who met in Berkeley, California, in the social protest movement of the 1960s, Harris has said she went into law enforcement to change the system from the inside. Yet as district attorney and then attorney general — and the first Black woman to hold those jobs — she found herself constantly negotiating a middle ground between two powerful forces: the police and the left in one of the most liberal states in America.

Harris declined to be interviewed for this article. But over the years, she has proudly labeled herself both a “top cop” and a “progressive prosecutor.”

All of which poses a question: Is Harris essentially a political pragmatist, or has she in fact changed? And is she the woman to lead a police reform effort from the White House?

Harris was elected San Francisco district attorney in 2003. The police union endorsed her in a runoff.

But in April 2004, barely three months into the job, Harris found herself at odds with police after a gang member gunned down an officer named Isaac Espinoza.

During her campaign, Harris had opposed the death penalty, in part, as being discriminatory toward people of color, and she did not seek it for Espinoza’s killer. Rank-and-file officers were infuriated.

In 2007, she stayed quiet as police unions opposed legislation granting public access to disciplinary hearings.

Police use of force had been a contentious issue in San Francisco long before Harris took office. From 2001 to 2004, The San Francisco Chronicle reported, there were more complaints about use of force in the city than in San Diego, Seattle, Oakland and San Jose, California, combined. Harris pursued few on-duty cases of force-related misconduct, though that was not unusual at the time.

Timothy Silard, Harris’ former chief of policy, said Harris experienced hostility in the department from the beginning. He recalled commanders and homicide detectives who refused to speak to her. Instead, they addressed white men — her subordinates.

“Did she set out as a professional prosecutor to anger the cops?” he asked. “No. Why would she do that? But did she shy away from doing bold things and important things because it was something the police department or police union didn’t like? Never.”

From 2002 to 2005, Black people made up less than 8% of the city’s population but accounted for more than 40% of police arrests. Silard and Paul Henderson, who was Harris’ chief of administration and now directs a city agency that investigates complaints about police, said Harris told her staff not to prosecute arrests based on racial profiling.

Harris also created a “reentry” program called “Back on Track” that aimed to keep young low-level offenders out of jail if they went to school and kept a job.

But some said she did not do enough.

“We never thought we had an ally in the district attorney,” said David Campos, who was a supervisor and police commissioner while Harris was district attorney and is now chair of the San Francisco Democratic Party. “You have someone saying all the right things now, but when she had the opportunity to do something about police accountability, she was either not visible, or when she was, she was on the wrong side.”

Calls to review police misconduct grew after Harris took office as attorney general in January 2011, in a state with a historically high rate of police shootings.

California law gives the attorney general broad authority over law enforcement matters. But aides to Harris said that she hewed to the state Justice Department’s hands-off policy, not interceding in officer-involved shootings unless the local district attorney had a conflict of interest or there was “obvious abuse of prosecutorial discretion.”

Brian Nelson, a top aide to Harris while she was attorney general, said she was reluctant to big-foot district attorneys, having been one herself.

On Aug. 11, 2014, two days after Brown was killed in Missouri, police officers in Los Angeles fatally shot Ezell Ford, an unarmed 25-year-old Black man with a history of mental illness, sparking a wave of demonstrations. Harris deferred to Jackie Lacey, the city’s first Black district attorney, who ultimately brought no charges.

Harris began her second term as attorney general the next year by outlining steps to make policing fairer and more transparent. Still, she refused to endorse AB-86, a bill opposed by police unions that would have required her office to appoint special prosecutors to examine deadly police shootings.

In San Francisco, police killed 18 people during Harris’ six years as attorney general. But if there was a single flash point, it was the shooting of 26-year-old Mario Woods in December 2015. Widely circulated cellphone videos showed officers surrounding Woods — disturbed, strung out on methamphetamines and armed with a steak knife. Five officers fired 46 rounds, hitting him with 21.

A series of rallies followed. Many believed that Harris would take action. Ultimately, it was the Justice Department that intervened.

“We weren’t absent,” said Venus Johnson, a former associate attorney general who advised Harris on criminal justice issues, adding that there were frequent discussions with San Francisco officials. “We weren’t putting our heads in the sand. We were actively involved.”

In 2016, former Rep. Loretta Sanchez, then vying with Harris for a Senate seat, made a campaign issue of police shootings, particularly her opponent’s refusal to support AB-86. That year, Harris offered a compromise to the bill that would expand her office’s authority to review police misconduct, but only if sought by district attorneys or police chiefs. California lawmakers are still considering the idea.

And after the election, a month before her Senate swearing-in, Harris began investigations of the Kern County Sheriff’s Office and the Bakersfield Police Department, where officers had been involved in multiple deadly shootings.

In her measured way, Harris pursued a variety of other criminal justice reforms.

One of her most lauded initiatives was OpenJustice, a database that provided public access to crime statistics collected by the state. That included data about the use of force and won the support of some police groups as well as activists.

“The decision I made was, ‘I’m going to try and go inside the system, where I don’t have to ask permission to change what needs to be changed,’” she said earlier this year.

As for her own career, she said, “I know we were able to make a change, but it certainly was not enough.”