By Jennifer Jacobs

From the pandemic’s earliest days, President Donald Trump was of two minds on coronavirus.

In public he was dismissive and belittling of the virus, and those who feared it. In private, for all his bravado, he acted like a man who dreaded catching it.

He told his then-chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney, to “stay the hell home” from a trip to India in February because he didn’t want to be around Mulvaney and his lingering cough, according to people familiar with the trip. Even before the virus, Trump was known to dart to the other side of the room if someone sneezed. He used medical wipes labeled “not for use on skin” to scrub his hands, along with the ever-present Purell.

Yet at the White House he shunned one of the simplest and most effective ways of preventing transmission -- wearing a mask. “Take that f---ing thing off,” he demanded more than once to aides who showed up wearing masks in the early days of the virus, when he’d been told they weren’t a fail-safe. “It doesn't look good.”

Mirroring his administration’s fitful efforts to combat the virus outside its walls, testing within the White House was viewed by some who worked there as ineffective. Some aides believed the White House didn't do enough to take basic safety precautions and wondered whether the public would be kept in the dark about any outbreak inside its walls.

Read | Lancet blasts Donald Trump's coronavirus 'disaster', urges vote for change

Walking into one coronavirus task force meeting in the Situation Room with Vice President Mike Pence, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin expressed alarm at the crowded space, according to several people present for the episode in the spring.

“We’re violating all the protocols!” Mnuchin said, dragging his chair away from the table. Pence began to orchestrate a rearrangement of the seating, with some attendees leaving the room to sit in an overflow area or join by telephone.

After that, the task force meetings were more socially distanced but masks at that point weren’t regularly used in the Situation Room even among the doctors, three people familiar with the gatherings said.

When Trump’s aide Hope Hicks fell ill on Sept. 30, even some people closest to Trump -- including his oldest son and namesake, Donald Jr., his son Eric, and daughter Tiffany, who all traveled with Hicks to the first presidential debate in Cleveland the day before -- weren't notified, according to people familiar with the events. They hadn’t been close enough to her on the plane to fall into the strict White House contact tracing protocols, defined as alerting people who had been within six feet of the infected person for at least 15 minutes in the last 48 hours.

The story of the president’s inability to protect his staff, his family and himself from coronavirus inside one of the most secure locations on earth is a microcosm of his administration’s inability to stop the spread across the nation, each battle shaped by the mindset and miscalculations of one man.

As the virus tightened its grip on the U.S, the White House itself became an incubator for infection. Since the onset of the pandemic, more than three dozen people close to the president have contracted the virus, though no one associated with the White House is known to have died.

Prominent advisers like Hicks, Kayleigh McEnany, Robert O’Brien and Stephen Miller. Secret Service agents, lesser-known staff members, valets and residence employees. First Lady Melania Trump, the president’s youngest son, Barron, and Kimberly Guilfoyle, his oldest son’s girlfriend. And of course, the president himself.

At least one more person contracted the virus -- a friend and adviser to Pence, Tom Rose, who is the first known person at the White House to test positive, according to several people, but whose identity was not disclosed until now. Pence’s office said Rose had no comment.

Pence’s team became the epicenter of another outbreak last month when several aides, including adviser Marty Obst, Chief of Staff Marc Short, personal assistant Zach Bauer and two other aides tested positive.

Months into the pandemic, with cases once again rising across the nation, the vice president’s office still leaned toward withholding information, publicly revealing Short’s case after questions from Bloomberg News. Pence has tested negative.

This account of how the White House let its vigilance slip to the point that the president himself fell ill is based on conversations with multiple people who work there or advise Trump. Each asked not to be identified because of confidentiality surrounding the events.

Their recollections provide the clearest view of how the White House failed to contain the virus in its quarters and the worry that spread among some in the complex. As Marine One carried the ailing president to the hospital on a Friday night in October, Trump’s aides and close allies called and texted one another, many expressing the same fear:

His illness would cost him the election.

A Nation Divided

In a statement, White House spokesman Judd Deere defended Trump’s handling of the virus, inside the White House and out, saying the president has advocated Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines and a “robust” contact-tracing program designed to stop the spread of the virus within the complex.

“President Trump’s top priority has been the health and safety of the American people which is why we have incorporated current CDC guidance and best practices for limiting Covid-19 exposure to the greatest extent possible, including staying home if you are positive or have symptoms, social distancing, good hygiene, and face coverings.”

“Any positive case is taken very seriously, which is why the White House Medical Unit leads a robust contact tracing program with CDC personnel and guidance to stop ongoing transmission,” Deere said. “If someone falls in a contact trace the Medical Unit makes appropriate notifications and recommendations.”

As masks and other precautions divided the nation, so too did they divide the Trump household. Melania Trump ordered masks worn in the East Wing and was at times taken aback to see her husband’s aides maskless in close quarters.

In the Oval Office, staff started arranging chairs 6 to 8 feet apart for meetings with the president. Some senior aides wore them in hallways but removed them when closed-door meetings began.

Ivanka Trump, the president's daughter, and Hicks, both senior advisers, wore masks in some meetings. Jared Kushner, another key Trump aide, as a rule did not.

Melania Trump instructed East Wing aides to work from home unless absolutely necessary and required masks in the office.

Rank-and-file employees who keep the White House complex running -- cleaning crews, handymen, building engineers and residence staff -- were among the first to follow the mask guidance carefully.

Because the first lady observed that West Wing staff didn’t always follow public-health guidance, she limited the number of aides traveling with her aboard Air Force One.

On one trip, when she boarded Marine One, she was perplexed to see none of the president's aides wearing masks, according to people familiar with the incident. Aboard the president’s plane on another journey, she asked if masks would be worn and was told yes. But as the first lady walked to the conference room to greet some members of Congress, no one she passed had a face covering.

“What is wrong with these people?” she said later, one person recalled.

Pence Aides Fall Ill the First Time

In late March, the vice president’s chief of staff alerted colleagues via a conference call that there was a case in their midst. The name -- Tom Rose, a former conservative talk radio host like Pence -- wasn’t shared on the call or in a public statement issued late on a Friday. The vice president's office said the unnamed aide had a right to privacy on a health matter.

Pence’s office said at the time neither the vice president nor Trump had close contact with the individual.

Some aides believed tracing was limited. The White House Medical Unit, charged with carrying it out at the complex, followed CDC guidelines, meaning it only informed those with whom the infected person had close contact for 15 minutes or more in the last 48 hours.

That left Rose’s co-workers to piece together their own informal contact tracing through word of mouth.

It wouldn’t be the last time -- some White House aides remained concerned throughout the year that the administration was relying on conservative CDC guidelines for contact tracing in order to keep to a minimum the number of people aware of infections, and therefore the chance of a leak to the press.

Read | Donald Trump does fear the coronavirus. Not with his words, of course

Deere, the White House spokesman, said White House contact tracing guidelines included that “appropriate recommendations are made to those deemed to be a close contact, but the essential work of the White House and the federal government must continue, which sometimes does require essential personnel to be physically in the office, and when that occurs every precaution is being taken to protect the health of the President, themselves, and the entire complex. The White House is following CDC guidelines for essential personnel.”

Virus fighters confront a case among them

Rose’s case and the flashes of outbreaks that followed fueled a certain fatalism inside the White House, as staffers tried to privately puzzle out the map of contagion. Trump's position was that he could neither shut down the nation nor the White House, and his aides followed him. The contagiousness of the virus and his staff’s frequent contact with outsiders as they ran a campaign and government led to one commonly held view: it was a miracle more aides hadn’t gotten sick.

Stephanie Grisham, Trump's press secretary at the time, experienced symptoms in mid-March after meetings with Brazilian officials who had the virus, although she never tested positive amid a shortage of rapid or reliable testing kits.

A second case in Pence's office followed a little more than a month after Rose's: The vice president's press secretary, Katie Miller, tested positive on May 8. Two days earlier, a White House valet had also turned up positive. Their cases brought the virus closer than ever to the president.

Trump’s team immediately ordered Pence’s staff out of the West Wing. The coronavirus task force relocated to a secondary Situation Room in a facility next to the White House, the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

Task force medical experts -- including Deborah Birx, Anthony Fauci and Health Secretary Alex Azar -- knew they had been in the same room with Miller the day before and realized they might be at risk of contracting the virus from her, according to several people familiar with the day’s events. Azar later told associates that she had stood right behind him.

Most members of Pence’s coronavirus task force were alerted to Miller's diagnosis by word of mouth, rather than formally by the White House Medical Unit’s contact tracing.

Miller’s case caused angst in the West Wing because of her regular presence in the cramped confines of the office complex.

A typical day took her from husband Stephen Miller’s suite on the second floor to the vice president’s workspace a floor below, where she’d often eat lunch in Marc Short’s office. Her role coordinating communications for the task force meant visits to the Oval Office, Situation Room, and press offices.

Trump privately worried she may have exposed him to the virus. And hours after she was diagnosed, he exposed her to the world.

“She’s a wonderful young woman, Katie. She tested very good for a long period of time and then all of a sudden today she tested positive,” Trump told reporters on May 8.

Fauci told aides who asked him for guidance to be particularly watchful for symptoms starting on days five to seven after exposure.

Pence was scheduled to travel to Iowa the day of Miller’s positive test. Some aides saw news reports noting that Air Force Two’s takeoff had been delayed, which was unusual, but weren’t told what was happening. Aides Bauer and Devin O'Malley left the plane but Short stayed on board himself, which later discomforted some travelers who knew how much time he spent with Miller. He later self-quarantined.

Trump gambles in Tulsa

From the pandemic's earliest days, Trump sought to project confidence and bristled at closing the economy to contain the virus. It was a move he accepted grudgingly and soon sought to reverse, by pressuring state governors to end lockdowns that caused unemployment to spike.

But the president was also left jumpy by coronavirus, even around top advisers. The president was never convinced Mulvaney, the chief of staff who stayed home from India, didn’t have Covid-19, according to two people familiar with his comments. Mulvaney himself later thought he had caught the virus on a trip to Ireland, though he never tested positive, according to two people.

Trump agitated to resume his signature campaign rallies as Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s lead in polls widened. He held almost two dozen events in 11 states between June and late September. But the first one -- on June 20 in Tulsa, Oklahoma -- stood out. Intended as Trump’s triumphant return to the campaign trail after a months-long, pandemic-induced pause, it instead led to what was then the single biggest outbreak connected to the White House.

At least three advance staffers, who prepare events for Trump’s arrival, fell ill, including the director of the team, Bobby Peede, and Francis Oley. About eight U.S. Secret Service agents were infected, some of whom had to drive home cross-country because they couldn't fly.

So many on the advance teams fell ill or were quarantined in hotels that extra staff, including Stephen May from the vice president's advance team, were scrambled to help set up the rally.

Colleagues were particularly worried about Peede, a popular figure who had a heart-related scare and was hospitalized during a presidential trip to Singapore in 2018. After he recovered from Covid-19, some aides privately told each other: If Peede can survive this virus, we can survive it.

Within six weeks, another lesser-known White House official would fall gravely ill. Crede Bailey, head of the security office and an overseer of credentialing for access to the complex, came down with the coronavirus over Labor Day weekend, landing him in the hospital.

The White House hasn't acknowledged his illness and Trump has said nothing publicly about Bailey, whose job requires working in a secure, enclosed space known as a sensitive compartmented information facility, or SCIF. Some coworkers said they weren't informed of his infection, and Bailey’s current condition could not be determined. His family requested privacy, a White House official said.

Guest lists grow

Through the summer and into the fall, the cases moved ever closer to Trump. His national security adviser Robert O’Brien, who sees the president most every day, caught the virus in July from his college-age daughter.

But the president remained defiant. When aides suggested shrinking guest lists for events, Trump added to them. Hundreds attended his convention speech Aug. 27 on the South Lawn, sitting shoulder to shoulder with few masks.

On Sept. 25, the White House switched its surveillance testing system from Abbott Laboratories’ ID NOW test to the company’s new BinaxNow test. The president was planning to announce two days later that his administration had secured 150 million of the new, credit-card sized rapid tests to distribute to states, in hopes they would encourage governors to reopen schools and businesses.

But first, Trump had another concern to attend to: preparing for the Sept. 26 announcement of Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, whom the president would introduce at a made-for-TV event in the newly refurbished Rose Garden before hundreds of supporters.

‘A lot of time with hope’

Looking back, some aides had suspicions about the new Abbott tests, worrying they weren’t accurate enough to detect cases that would seed an outbreak in official Washington. Others rejected that, with one senior aide saying the White House ruled out testing as the sole problem.

Abbott has said both tests have demonstrated accuracy of at least 95% in identifying both positive cases and negatives. Independent studies have shown lower accuracy rates for the company's earlier test, ID Now.

Read | 18 Donald Trump rallies estimated to have led to over 30,000 Covid-19 cases, 700 deaths: Study

Aides who attended the ceremony for Barrett were told as they walked in that nobody else was wearing a mask, so they could remove theirs, too. In the coming hours, Trump would hold debate prep sessions in the Map Room and Oval Office.

As Trump arrived in Cleveland on Sept. 29 for his first debate with Biden, he was showing what one person close to him thought, in hindsight, might have been early signs of illness, visibly perspiring and looking flushed. Others thought he was merely irritable because of the debate.

The White House declined to comment on whether Trump was tested that day, though the Cleveland Clinic said in a statement that “individuals traveling with both candidates, including the candidates themselves, had been tested and tested negative by their respective campaigns.” Trump himself shrugged off the question when asked at an NBC town hall whether he'd been tested before the first debate. “I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t even remember.”

By the time Trump traveled to Minnesota for a fundraiser and rally the day after the debate, he very likely had an active infection and was potentially spreading the virus. Aides noted how tired he seemed that day -- he was unsteady on his feet, spoke only about 45 minutes, and slept so hard on the flight back he had to be shaken awake.

Hicks, one of his closest advisers, was in close proximity to other top aides on the trip, including Kushner, social media director Dan Scavino and personnel chief John McEntee. Hicks had tested negative before departure; she started feeling ill after the fundraiser and isolated in an office cabin on Air Force One during the Duluth rally and the return flight to Washington. Scavino, Kushner and McEntee were not infected by Trump or Hicks, according to several people.

The day after the Minnesota trip, Hicks’s diagnosis was kept secret from all but a very small group of officials. Trump kept up his public schedule, arriving back at the White House from a New Jersey fundraiser shortly before 6 p.m. Within two hours Bloomberg News reported that Hicks had tested positive.

Trump, consulting with his physician, took a rapid test that came back positive, according to people familiar with the matter. His medical team wanted a more reliable polymerase chain reaction test, and as he spoke on Fox News host Sean Hannity’s show, Trump’s concern was evident.

“So I just went for a test and we’ll see what happens. Who knows?” Trump told Hannity. “We spend a lot of time with Hope.”

Despite the president's reluctance, Trump's aides had held discussions about the need to inform the public. At 12:54 a.m. on Oct. 2, Trump announced via Twitter that he and the first lady had the virus. “We will get through this TOGETHER!,” he wrote, within an hour of learning about his diagnosis.

Family, aides kept in the dark

Trump’s close family weren’t the only people who initially weren’t told of Hicks's infection. Several top advisers also weren't told, including former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, then-counselor Kellyanne Conway and campaign manager Bill Stepien. They had all participated in debate prep earlier in the week with Trump and Hicks, sought testing after the news about Hicks broke, and discovered they too were infected. It is not clear where they contracted the virus.

Trump privately grumbled that he hadn't wanted to do debate prep in the first place.

The severity of Trump's condition was kept under wraps, while the White House provided conflicting information to the public. His doctors declined initially to say whether he was given oxygen before acknowledging that he had in fact received it on Oct. 2 before his hospitalization at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

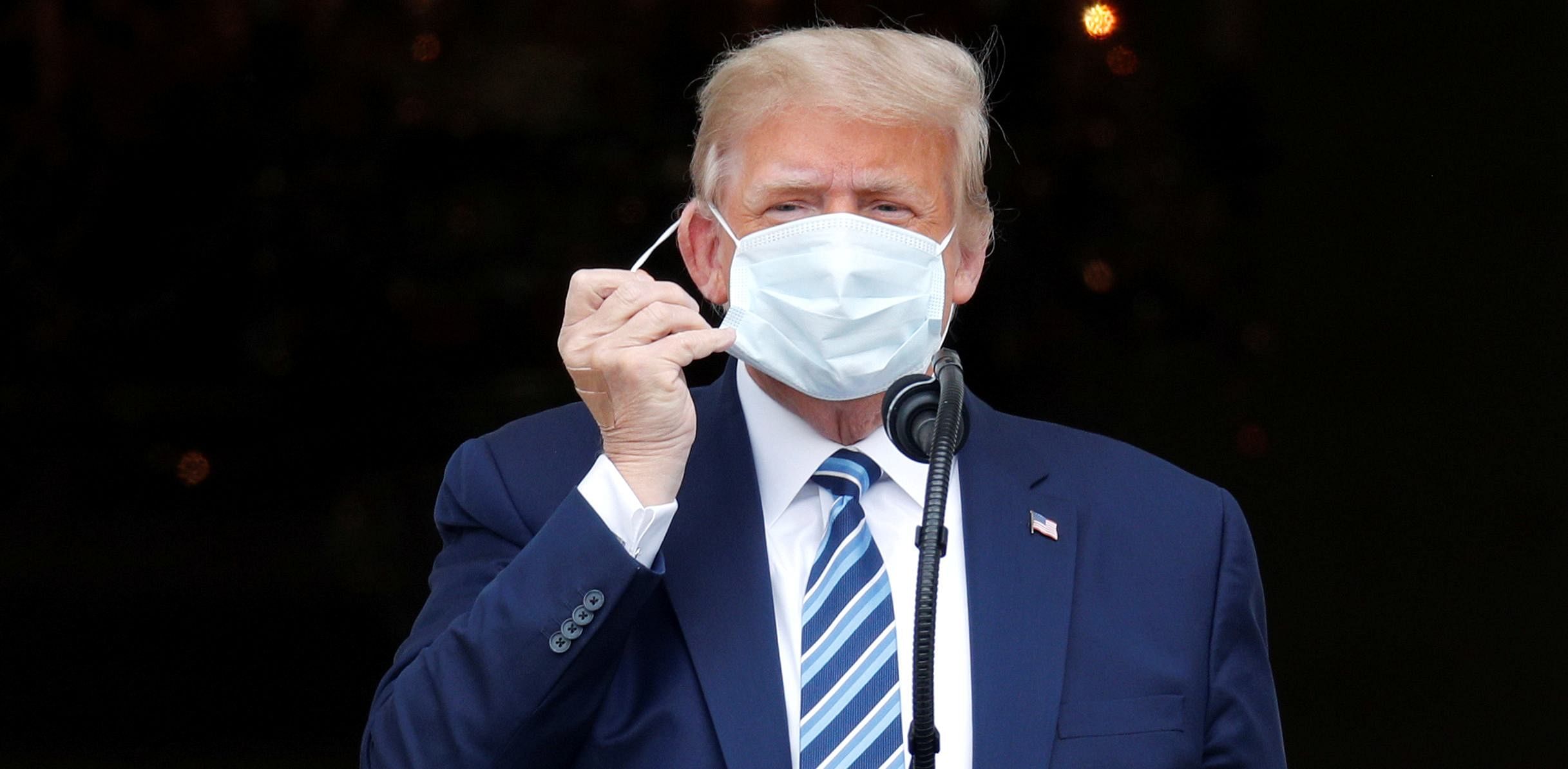

Upon his return to the White House on Oct. 5, Trump showed no sign of being chastened. If anything, aides said, he had a renewed sense of invincibility. After descending from Marine One, he walked up the stairs outside the White House to the Blue Room balcony, overlooking the South Lawn, where he removed his mask, flashed a thumbs-up with both hands and saluted for several seconds. He was breathing heavily.

Trump on Oct. 8 said he could have stayed home instead of going to Walter Reed.

“I didn’t even have to go in, frankly,”he said on Fox Business. “I think it would’ve gone away by itself.”

‘I knew there’s danger’

Aides no longer believe Trump is certain to lose re-election but acknowledge that his path to a second term is tougher.

Publicly, he still talks dismissively about the pandemic, repeatedly telling his rally audiences that the country is rounding the turn and the virus will go away. Yet it remains very much on the minds of Americans who've lost their jobs or loved ones, who can’t return their children to school, who still limit their social interactions and travel.

Trump often highlights his own recovery, offering himself as living proof that the virus wasn't as bad as everyone thought. In a video released the night he returned from Walter Reed, Trump invoked his illness as a sign of strength, presaging the message he hoped would return him to the White House.

“I knew there’s danger to it. But I had to do it. I stood out front. I led,” he said. “Nobody that’s a leader would not do what I did.”